Prepared for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Supplier name: Earnscliffe Strategy Group

Contract number: CW2248846

Contract value: $74,994.71

Award date: November 29, 2022

Delivery date: February 10, 2023

Registration number: POR 084-22

For more information on this report, please contact Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at: aafc.info.aac@agr.gc.ca.

Ce rapport est aussi disponible en français.

2022-23 Qualitative Research on Consumer Perceptions of Sustainability-Oriented Food Assurance Systems

Final Report

Prepared for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Supplier name: Earnscliffe Strategy Group

March 2023

This public opinion research report presents the results of focus groups conducted by Earnscliffe Strategy Group on behalf of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. The fieldwork for the qualitative research was conducted in January 2023.

Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre : Recherche qualitative sur les perceptions des consommateurs à l'égard des systèmes d'assurance alimentaire axés sur la durabilité, 2022-2023.

This publication may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes only. Prior written permission must be obtained from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. For more information on this report, please contact Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at: aafc.info.aac@agr.gc.ca or at:

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

1341 Baseline Road

Ottawa, ON K1A 0C5

Catalogue Number: A22-681/1-2023E-PDF

International Standard Book Number (ISBN): 978-0-660-47990-3

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Number: 13155E

Related publications (registration number: POR 084-22)

Catalogue Number: A22-681/1-2023F-PDF (Final report, French)

International Standard Book Number (ISBN): 978-0-660-47992-7

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food, 2023

Earnscliffe Strategy Group (Earnscliffe) is pleased to present this report to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) summarizing the results of qualitative research undertaken to understand consumer drivers of use of and expectations around sustainability-oriented food assurance systems.

Budget 2019 committed an investment of $25 million over five years for Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC) to develop a national approach to better connect Canadians with and instill pride in Canada's food system and the agriculture sector. The AgriCommunication Initiative (ACI) objective is to increase appreciation and pride in the contribution of farmers and the food industry and enhance public trust between Canadians and farmers.

As a result, AAFC wanted to better understand consumers' current and future use and perception of assurance systems and labels. Assurance systems refer to the processes and procedures that provide confidence and trust that associated risks along the food supply chain are adequately addressed and claims can be proven. For instance, that the food is safe, and meets market requirements. AAFC works with the sector to ensure that systems, standards, and tools, including assurance labels which signify a comprehensive assurance system behind it, are developed to support its ability to prevent and control risks and address market demands.

At this time, AAFC wanted to conduct qualitative research to build on the quantitative research they did investigating awareness of assurance labels. The primary objective of this research was to explore the role of and understanding of assurance labels, key drivers, and barriers, as well as needs and perceptions of sustainability-oriented assurance systems and labels. The contract value for this project was $74,994.71 including HST.

To meet these objectives, Earnscliffe was retained to conduct a series of twelve (12) focus groups between January 23 and 25, 2023. The audience for the research was adults aged 18 and older who have joint/sole responsibility for grocery shopping in their household. Five (5) regions of the country were studied: British Columbia/Territories (British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut), Prairies (Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba), Ontario, Quebec (in French), and Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador). Two groups were conducted in each region, segregated by age: "young adults," 18 to 34 years of age and "adults," 35 years or older. In addition, two groups were conducted with adult consumers identifying as Black, Indigenous, or other Person of Colour (BIPOC) — one in English (with participants from across the country) and one in French (with participants from across Ontario and Quebec).

It is important to note that qualitative research is a form of scientific, social, policy, and public opinion research. Focus group research is not designed to help a group reach a consensus or to make decisions, but rather to elicit the full range of ideas, attitudes, experiences, and opinions of a selected sample of participants on a defined topic. Because of the small numbers involved, the participants cannot be expected to be thoroughly representative in a statistical sense of the larger population from which they are drawn, and findings cannot reliably be generalized beyond their number. As such, results are directional only.

The key findings of this research are presented below.

Research firm: Earnscliffe Strategy Group (Earnscliffe)

Contract number: CW2248845

Contract value: $74,994.71

Contract award date: November 29, 2022

I hereby certify as a representative of Earnscliffe Strategy Group that the final deliverables fully comply with the Government of Canada political neutrality requirements outlined in the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada and Procedures for Planning and Contracting Public Opinion Research. Specifically, the deliverables do not include information on electoral voting intentions, political party preferences, standings with the electorate or ratings of the performance of a political party or its leaders.

Signed:

Stephanie Constable

Principal, Earnscliffe

Date: February 10, 2023

Earnscliffe Strategy Group (Earnscliffe) is pleased to present this report to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) summarizing the results of qualitative research undertaken to understand consumer drivers of use of and expectations around sustainability-oriented food assurance systems.

Budget 2019 committed an investment of $25 million over five years for Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC) to develop a national approach to better connect Canadians with and instill pride in Canada's food system and the agriculture sector. The AgriCommunication Initiative (ACI) objective is to increase appreciation and pride in the contribution of farmers and the food industry and enhance public trust between Canadians and farmers.

As a result, AAFC wanted to better understand consumers' current and future use and perceptions of assurance systems and labels. Assurance systems refer to the processes and procedures that provide confidence and trust that associated risks along the food supply chain are adequately addressed and claims can be proven. For instance, that the food is safe, and meets market requirements. AAFC works with the sector to ensure that systems, standards, and tools, including assurance labels which signify a comprehensive assurance system behind it, are developed to support its ability to prevent and control risks and address market demands.

At this time, AAFC wanted to conduct qualitative research to provide a deeper understanding of sustainability-oriented food assurance systems. The primary objective was to explore role of and understanding of assurance labels, key drivers, and barriers, as well as needs and perceptions of sustainability-oriented assurance systems and labels.

The specific objectives of the research were to understand:

To meet these objectives, Earnscliffe was retained to conduct a series of twelve (12) online focus groups between January 23 and 25, 2023. The audience for the research was adults aged 18 and older who have joint/sole responsibility for grocery shopping in their household. Five (5) regions of the country were studied: British Columbia/Territories (British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut), Prairies (Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba), Ontario, Quebec (in French), and Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador). Two groups were conducted in each region, segregated by age: "young adults," 18 to 34 years of age and "adults," 35 years or older. In addition, two groups were conducted with adult consumers identifying as Black, Indigenous, or other Person of Colour (BIPOC) — one in English (with participants from across the country) and one in French (with participants from across Ontario and Quebec). The table below shows the composition, date, and time of each group, as well as the number of participants per group.

A total of 81 Canadian consumers participated in the focus groups.

| Group Number | Date | Audience | Region | Time | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT | 7 |

| 2 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Quebec (FR) | 6:00 pm ET | 8 |

| 3 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | BIPOC | English | 7:00 pm ET/8:00 pm AT/8:30 pm NT/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT/4:00 pm PT | 6 |

| 4 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT | 8 |

| 5 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Quebec (FR) | 5:00 pm ET | 7 |

| 6 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET | 4 |

| 7 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT | 7 |

| 8 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT | 7 |

| 9 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | BIPOC | French | 5:00 pm ET/6:00 pm AT/6:30 NT | 7 |

| 10 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET | 8 |

| 11 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT | 6 |

| 12 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT | 6 |

The focus group sessions were approximately 90 minutes in length. Participants were given an honorarium of $100.00 as a token of appreciation for their time.

Appended to this report are the recruitment screener, discussion guide, and concepts presented to participants during the groups.

It is important to note that qualitative research is a form of scientific, social, policy, and public opinion research. Focus group research is not designed to help a group reach a consensus or to make decisions, but rather to elicit the full range of ideas, perceptions, attitudes, experiences, and opinions of a selected sample of participants on a defined topic. Because of the small numbers involved, the participants cannot be expected to be thoroughly representative in a statistical sense of the larger population from which they are drawn, and findings cannot reliably be generalized beyond their number.

Quotations used throughout this report were selected to bring the analysis to life and provide unique verbatim commentary from participants across the various audiences.

The following qualitative results are divided into five sections: 1. Views toward Canada's agriculture and food sector; 2. Environmental sustainability perception and influence on behaviour; 3. Awareness of, trust in, and impact of assurance systems and labels; 4. Common assurance system and label; and 5. Communications preferences.

Discussions began with an initial context setting conversation to understand consumer perceptions of and trust in Canada's agriculture and agri-food sector.

As with past studies, when consumers think of Canada's agriculture and food sector, the first things that come to mind tended to be positive images of food products (for example, grains, fruits or berries, vegetables, meat, and dairy), as well as local farmers and farmers markets.

Perhaps not surprisingly, especially given the current economic situation, rising food prices and the cost of groceries also came up. In fact, price-sensitivity was an undercurrent that was mentioned throughout the discussions, as we will see in this report. Worth noting, this is consistent with the 2022 Qualitative Research on Consumer and Producer Views Towards Sustainability in Agriculture study.

"I have definitely cut back on unnecessary purchases." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

"If you thought the $10 head of cauliflower was expensive in Yellowknife, you should see the organic!" — Young adult 18 to 34, British Columbia/Territories

When asked to rate their level of trust in Canada's agriculture and the agri-food sector in general, using a 10-point scale, most responses indicated a positive sense of trust, although there was some diversity of opinion. The majority (54/81) of participants provided Canada's agriculture and food sector with a trust rating between 7 and 10. Twenty-five provided a rating between 4 and 6, and 2 participants provided a rating between 1 and 3.

| Poll responses | Young adults (18 to 34) |

Adults (35+ or older) |

BIPOC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating 7 to 10 | 21 | 28 | 5 | 54 |

| Rating 4 to 6 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 25 |

| Rating 1 to 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 32 | 36 | 13 | 81 |

| Poll responses | Atlantic Canada | Quebec | Ontario | Prairies | BC/ Territories |

National (BIPOC) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating 7 to 10 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 54 |

| Rating 4 to 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 25 |

| Rating 1 to 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 15 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 81 |

Across the various audience segments, adults 35 and older seemed to be the more trusting of the three. BIPOC participants often provided a rating between 4 and 6 and the conversations suggested that there did seem to be more mid-level trust in Canada's agriculture and food sector. Comparisons were often made of the Canadian agriculture and food sector to those of other parts of the world (Europe and Africa were mentioned). The sense was that regulations were laxer, in Canada, especially around the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and pesticides.

"For me, I think there are too many GMOs. It's not natural here. Products are deformed. They taste different [not as good]. It's not good for our health." — BIPOC, French

"I rated them a 2. Canada has to have more strict regulations around GMOs and pesticides. Our food is too heavily influenced by the industry. In Europe, they banned GMOs." — BIPOC, French

Regionally, the directional insights in the tables above suggest that residents of Atlantic Canada and Quebec were more trusting of Canada's agriculture and food sector.

Alongside the mostly positive or neutral trust ratings, participants often explained that they have not been given a reason to mistrust the sector; that they trusted the "high level" of regulation that backed that industry; or did not have enough information to inform a different rating.

"I never hear of any scandals." — Young adult 18 to 34, Quebec

"I am fairly confident in our ability to grow food safely. There's a lot of regulations to ensure it's safe." — Young adult 18 to 34, Ontario

"I think 'Made in Canada' is a sign of quality." — BIPOC, English

While not always stated without further probing, many participants said that they had more trust in "local" or "smaller" operations/farmers and less trust in large producers or "factory farms."

"As businesses get a bit bigger, I get more cautious." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

"I tend to trust the small and local farmers more, and less the big production stuff. You get more of a personal touch with small farmers. Whereas, the big farmers are more business focused, and just trying to get out as much as they can, as fast as they can." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

To build trust in Canada's agriculture and agri-food sector, participants were asked what they would need to see or learn. Those who were able to offer a perspective suggested more transparency, information regarding regulations, who (farmers and/or producers) is financially compensated and how much.

When asked what sustainable means as it relates to agriculture and the agri-food sector, consumers tended to be somewhat divided between supply-related responses (for example, availability, consistency, reliability) and environmental-related responses (for example, growing methods, emissions due to transportation, stewardship of the land). A few participants in the groups with residents of British Columbia and the Territories also noted that it could mean being sustained by food.

"I go to the grocery store, and I see shelves empty. And, I wonder, will I have food tomorrow?" — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

"Renewable, humane conditions for livestock and chickens, and the land is being reused and not destroyed." — Adult 35 and older, British Columbia/Territories

"To produce what it is we need, without overworking the land or taking more than we need." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

Discussions explored impressions of environmental sustainability as it relates to agriculture and the agri-food sector in Canada, as well as whether or how it influences food purchase behaviours.

In terms of whether food produced in Canada is produced in an environmentally sustainable manner, most were apathetic claiming that they did not know, but many indicated that they assumed it was. Several participants felt that they should know more but had not taken the time to research properly. Others, as noted earlier, were generally trusting of Canada's agriculture and food sector, and said they did not think much about how our food is produced, especially from an environmental perspective. One adult 35 and older who resides in Quebec explained that "I have respect for our norms. I think we have a lot of inspections and high-quality standards here [in Canada]." Incidentally, those who considered Canada in a comparative, international context, tended to commend Canada for being a country with responsible standards, though this was less prevalent among those who identify as BIPOC.

Having said that, some did offer that they have the feeling Canada's agriculture and agri-food sector may not be environmentally sustainable, or at least, that their impression would probably depend on what food was being considered. For example, some pointed out that beef cattle was a particular challenge in terms of emissions. Others expressed concern around: transporting food long distances (particularly to the North); the use of GMOs and pesticides; issues such as run-off; superfluous product packaging; food scarcity and food waste. These concerns were particularly acute among residents of rural communities, particularly those in the Territories, who often noted how far food has to travel to get to them and the challenges that brings with respect to availability, choice, and cost.

With respect to the use of pesticides, there certainly was a perception across the various discussions, that the practice is not desirable. When asked to explain why using pesticides is of concern, participants explained that they fear the ingestion of chemicals is not good for our health. A few mentioned linking the increased prevalence of health conditions (for example, cancer mentioned often) to the ingestion of more chemicals (from our food products). Often while having these conversations other participants would argue that to meet the increased global demand for food, farmers/producers must rely on these products. As one adult 35 years and older from the Prairies said, "It is so much more challenging for farmers to grow their crops the way they would like without as many pesticides. To compete, they don't have a choice."

Lastly, while not all participants were sure how sustainability related to their own purchases or consumption behaviour, when asked how they can tell whether a food/product is environmentally sustainable, the most common mentions were buying local or at a farmers' market, and choosing products that have less packaging (or products with packaging that is recyclable or biodegradable).

With respect to buying local, one frequent caveat raised had to do with the size of the operation, with many sharing the view that they feel smaller operators are more likely to be operating in environmentally responsible ways than larger, often described as corporate, operations.

"Dependent on who it is, where it is from. I don't think bigger companies would fall under that as much," — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada.

"I shop local at farmers markets. They have free range, which means they're not being cruel to animals. It's not factory farming." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

When asked if they seek out food that is produced in an environmentally sustainable way some participants in each group said that they did, although it was not the majority. Indeed, the overwhelming majority of participants indicated that price was the primary factor influencing their purchase decisions. Those who do look for food produced in an environmentally sustainable way noted that they use the product packaging and assurance labels to identify sustainably produced food. Others explained they referred to how a product is packaged, and some referred to the products origin, with preference for products that come from somewhere closer to home (and therefore do not have to travel as far) but at minimum produced within Canada.

Also worth noting, some residents of rural communities, particularly those in the Territories, noted that environmental sustainability of their food is not something they consider as they try to rely more on sources of food that come from the land and waters.

Though still not the majority, young adults 18 to 34 appeared to be more likely than adults 35 years and older to seek out products produced in an environmentally sustainable way, at least some of the time. This tended to skew to younger adults who still reside with family (for example, parents, siblings, or other family members), and do not have the responsibility to purchase everything they consume. These young adults noted researching producers' reputations online, and assessing the distance products travel as an indicator of environmental sustainability.

"I wouldn't know how to look for sustainability. Except for seafood that clearly outlines it, we really don't know. We just trust that it is." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

"Some days I go out and read the labels, but it's not every item." — Young adult 18 to 34, Ontario

"I'll look for it on the label if it's right there." — Young adult 18 to 34, British Columbia/Territories

"I'm geared toward the price but also the packaging. If they have a lot of single-use plastic, I probably won't go that way." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

Discussions explored participants' unaided and aided views of assurance systems and labels as well as the role of assurance labels in purchase decisions.

Unaided recall of assurance labels was limited. While some in every group mentioned seeing assurance labels with claims about such things as organic, non-GMO, free-range, or fish caught in a sustainable (or responsible) manner, every group had as many or more that were unable to recall such things voluntarily.

Aided recall of three examples (please refer to Appendix E to see what was shown to participants) was much more widespread. Showing participants the examples of assurance labels clearly stimulated some who had no unaided recall to say they had seen at least one of these three examples. As examples go, there was recognition of each of these assurance labels to varying degrees. Those who could recall any of these assurance labels also seemed to hold them in fairly high regard.

Credibility of existing assurance labels varied widely among participants and by type of claim. Some participants suggested they take claims at face value while others seemed to regard them more skeptically. Trust in assurance labels was described as being related to a variety of factors largely amounting to the level of experience and information people felt they had about them. The information gathered can be from an extremely wide, and at times conflicting, variety of sources. These can include scientific information, advice from experts, or messaging put forward by documentaries — often the ones that present "dirty secret" type of exposés that cast doubt on claims.

"In order to get that label, they've had to go through some sort of process." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

"I think they're a step in the right direction, but I think there are still gaps and areas to improve. I'd rather see labels like these than no assurance labels at all." — Young adult 18 to 34, British Columbia/Territories

"Generally those labels make me cynical but if I have to choose between a product with one or without one, I will choose the product with the label." — Adult 35 and older, Prairies

"I'm not saying people do distrust, but they are certified for a certain amount of time. How do we know that one week after they are certified things don't go sideways? I'm not sure how often re-certification occurs." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

"Organic means it is without pesticides or GMOs. The products will be more sustainable but are they all 100%? Not necessarily." — Young adult 18 to 34, Quebec

Trust aside, roughly half of participants felt that assurance labels were helpful to widely varying degrees. A few participants felt strongly in favour of assurance labels, while others described them as "better than nothing." Few participants felt armed with enough knowledge about the number of assurance labels to say whether there were too many or too few on the market, but as one young adult 18 to 34 who resides in Quebec said, "Today, stickers are put everywhere. You can't have confidence in them." Others, even with prompting, had trouble recalling seeing assurance labels while shopping. As such, they had not formed much of an impression of what the assurance label might mean or if it would be important to them.

"It's not that I feel a particular way, it's that I don't think of these. I feel like I don't overanalyze the labels when I am buying things. I am sure these are great programs, but in my day-to-day life, I am not thinking about it." — Young adult 18 to 34, Ontario

"I'm realizing I am not looking at my food closely enough!" — Adult 35 and older, British Columbia/Territories

In terms of the impact these assurance labels have on purchase intention, few were willing to say they have had much impact on their behaviour. Indeed, price continues to be the most influential factor on the vast majority of participants' purchase intentions. Some participants, and perhaps slightly more among young adults 18 to 34, offered an "all other things being equal" assessment of their impact, saying that an assurance label would tilt in a products favour, but only in certain circumstances (that is, price being equal). At the same time, most groups included a few participants who said they are more inclined to make a sacrifice (usually of money) to choose more environmentally sustainable products or support more responsible producers.

"It doesn't mean that I would be buying the more sustainable product, but it might make me rethink what I am buying." — BIPOC, English

"I don't put too much weight on the labels. I probably would still pick one with a label over one without, but in the back of my mind, I don't trust it." — Adult 35 and older, British Columbia/Territories

A minority of participants questioned whether these kinds of assurance labels were necessary especially as it related to food or products that were grown or produced in Canada. Again, the majority believed that they were already safe, sustainable, and healthy.

"Why doesn't all our food meet the organic stamp of approval?" — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

"In an ideal agricultural system, we wouldn't need labels because everything would be grown safely and ethically." — Young adult 18 to 34, Ontario

"The fact that labels are there means there are actually grey areas. Would prefer to be able to trust the agriculture more and do not have to look for labels to feel assured to buy food." — Young adult 18 to 34, British Columbia

Purchase intentions were impacted, at least in part, by the common barriers mentioned; that is, price and lack of understanding (and therefore trust) in what the assurance label claimed (and how it was enforced). A common lack of understanding example provided was for egg products, where there are 'free range' and 'free run' labels, which were confusing to every participant that mentioned them. Adults 35 years and older were more likely to cite multiple barriers, whereas young adults were more likely to name price on its own.

"My situation is that I am just coming off EI. Labels don't mean much when I can't afford it. Price determines." — Adult 35 and older, Prairies

"We need more information to understand them, otherwise it's just a slogan." — Young adult 18 to 34, Quebec

"Is my family going to eat it, and is it on sale? That's what I am concerned with." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

"I don't think it matters to have labels on the food if people don't know what the label means. Unless you know specifically what trials they went through for that label, I don't think it changes people who are skeptical." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

For assurance labels to be impactful, participants indicated a need to know what the assurance label represents and how it is validated. Over and over, participants said that more than anything, what they need to know is that there are meaningful standards being met and the adherence to them is rigorous and verified by some sort of respected body. Discussions often uncovered a sense that even some assurance labels that are recognized (with prompting) may have good intentions but the motivations and adherence are not always assumed to be the best.

Some assurance labels are seen as marketing tools, merely designed to trigger a purchase and not as altruistic as they appear. At worst, a few participants felt that these kinds of assurance labels could be obtained illegitimately, either with money or coercion. One young adult 18 to 34 who resides in British Columbia/Territories asked, "Can't companies just go and buy those seals?" It appears that in most cases, these perceptions were informed by things read or seen in media or documentaries (as noted above).

Some assurance labels are understood to be veiled claims that distract from other, possibly, greater drawbacks of a product. A common example was in transportation of goods, which to many was as important a factor as any other assurance label claim. For example, participants noted that a product could be organic, but the fact it may have traveled across the continent to get to Canadian grocers, detracts from their sustainability claims.

Nevertheless, participants expressed both an appetite and aspiration for assurance labels that would provide them with the comfort that a product was produced to standards that help ensure the healthiness of the product and the environment in which it was grown or produced. In terms of environmental sustainability, participants responded they consider if the product is local (where it originates); the distance travelled to market; whether it is genetically modified, or pesticides have been used; whether the animals were treated humanely; that farmers were appropriately compensated; and that the product is packaged with the least amount of packaging possible or that the packaging materials are made from environmentally responsible materials.

"Location; wages for farmers; humane practices (for animals); packaging; and transparency to name a few criteria." — Young adult 18 to 34, British Columbia/Territories

"Growing foods that need as little chemical enhancements as possible and that are native to the area of growth." — Adult 35 and older, British Columbia/Territories

Asked whether they had a preference between a simple assurance label or one that offered a graded rating, reactions were mixed. Both approaches had some participants preferring them, but a lot would depend on the details. The simple assurance label was easy enough for participants to grasp and yet, their appreciation for it was dependent upon many aspects already discussed above. Participants who preferred a simple assurance label often indicated that 'the public' would not understand a graded system, rendering it ineffective in changing purchase behaviour. Some participants said that a simple assurance label would be easier to teach to children, which is where they felt education should start.

"The simpler, the better it is. A simple label will be better. And it will be easier to teach." — BIPOC, English

"I prefer a simple one, as long as there was a place to look into how it actually passed it." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

For a more complex, graded assurance system and label, many described it as potentially being of interest, but they had a lot of questions or caveats to offer. For example, a grade-rating felt to some like they could make a judgement, but others felt like they could not immediately grasp what all was being considered. Those who were most appreciative of the graded approach tended to be doing so out of recognition of the fact being sustainable is complex and involves a wide variety of behaviours including such things as emissions, land stewardship, efficient (or no) use of undesirable chemicals, ethical treatment of animals, and fair treatment of people (that is, producers and employees). Some suggested a checklist approach that might demonstrate which standards a product was certified on, possibly allowing consumers to steer towards products that pass certification on aspects of greater importance to them.

"If your product had a C or a D, you might prefer not to have a label at all." — Young adult 18 to 34, Ontario

"I prefer grading so more products would have a label, even if it were a poor grade." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

Most groups included at least one participant who worried that a grading system would not be effective as producers who were graded poorly would opt-out of the system all together.

The oversight of an assurance system and label was seen as key. Having industry self-regulate was seen as the most problematic approach by many, but that did not mean they felt industry could not be entrusted with vital roles in design and implementation. Certainly, in the case of agriculture and agri-food, participants consistently felt that farmers — and typically, this was intended to mean smaller and/or non-corporate operations — should be involved in the determination of what behaviours and practices constituted the most responsible set of standards.

Discussions sought to elicit participants' views related to a common assurance system and label including their hopes, and desires for that system, and who they would trust to manage and certify it.

To understand participants' views related to a common assurance system and label, participants were shown examples of an assurance system and label used in the United Kingdom (UK) known as, Red Tractor. Information was provided that explained that this assurance system and label was created by the agriculture industry in the UK to help consumers easily identify the assurance label and know the standards (that is, food safety, environmental sustainability, and animal welfare) behind it.

Reactions to the Red Tractor assurance system and label were broadly positive, even if some identified room for improvement, particularly as it relates to industry management of the program. When provided with visuals and a basic description of the assurance system and label, participants tended to react favourably. There were a number of key strengths identified by participants, often relating directly to concerns they had raised earlier in discussions, such as:

As mentioned, industry management of the Red Tractor program was met with mixed reactions. Of all aspects shared about the assurance system and label, that element was, above all, the most likely to stimulate debate about benefits and drawbacks. Many participants indicated needing to know more about how industry management of the program worked and, more to the point, whether that worked, in order to feel comfortable with that approach. Oversight was cited as a key element to instilling long-term confidence in, and value of, such assurance labels.

"I want the government stamp on this. If I am industry, I'm going to say, 'my stuff is good.'" — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

"An unbiased third party. Because then I feel like the farmers have the right input." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

Most clearly indicated that a common assurance system and label like this could be worth establishing in Canada; mainly for the strengths cited above. If it were to work as intended and hoped, most participants felt it would be beneficial and may be an influence on some purchase behaviours. In fact, a few imagined the intrinsic value and net sustainability benefit of compounding purchases of multiple products with the common assurance label.

"If enough products had that label on them, so you weren't just looking for a few things. Because it makes me feel like I am making a difference. If I am just buying lettuce with that label, it doesn't feel like I am making a difference. But, if I am buying 10 things with that label, I would feel like I am making more of a difference." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

"Easily identify that it's Canadian. For my family, we try to buy Canadian when we can. This would make it really easy to identify." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

That said, there were some drawbacks identified by participants; the biggest being (and raised by many) price/cost. There was an assumption that the price of products with this assurance label would be higher. Participants reasoned that this kind of assurance system may cost farmers money which would, in turn, be passed along to consumers who are already struggling with the cost of food. However, the more participants assumed that their preferred producers and products are already living up to certain standards they cared about, the more this would help validate the participants' continued purchasing.

"It should not cost anything for the manufacturer. It shouldn't be a sign of high price. I don't want people who have the means to be able to eat things that are healthy, or that are good for the planet. Everyone eats food so it should be democratic." — BIPOC, English

"I am heavily influenced by price, especially now. I do try to buy local and Products of Quebec, but I don't think I would do a 360 and only buy [Red Tractor] but I'd do what I could." — Young adult 18 to 34, Quebec

The other drawbacks participants mentioned were that the standards would be vague or lack stringency; that the vastness, regional, cultural, and climatic differences across our country could complicate a common program; and, that there may not be adequate auditing or oversight.

"Who would the panel of experts be and would smaller regions have an equal voice in that system. What might work in some regions, may not be sustainable in other regions, even culturally." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

In terms of oversight, the desire was for third-party independent involvement. As one young adult 18 to 34 who resides in Quebec explained, "Third-party independent is the best. When it's not people who are directly involved or who have interests, the certification is better respected." When asked who they would trust to manage it, preference leaned toward the involvement of a consortium of partners including industry but also farmers/producers, consumers, scientists, non-government organizations (NGOs), and government officials.

The role participants had in mind for government was around oversight, regulation, inspection, enforcement and subsidization. Because this would be a common assurance system and label, participants worried that some smaller operations, may be required to make investments in their operations and/or practices to qualify for the program and remain competitive (and in business), which may require government assistance (subsidization). Further, given the lack of awareness or consistent reliance on such, they felt government would need to play an important role in raising public awareness and education about the assurance system and label. As one young adult 18 to 34 who resides in Quebec noted, "I would like to see them involved in public awareness. They need to use social media, TV, to make people aware of the program, what is involved, what they [farmers/producers] need to meet to be certified."

Discussions investigated participants' information needs and where they would turn for information about a common assurance system and label.

In terms of information needs, what participants would most like to understand about the assurance system and label are the sustainability practices and guidelines that would be required for accreditation. More than anything, participants would like to know these practices constitute the right mix of behaviours that truly deserve to be encouraged.

"I would like to know what it takes to get the label, like which regulations were met in order to have this label on the product." — Young adult 18 to 34, Ontario

"How this program works? Who's involved? I'd like the details about certification and the impacts on the environment." — BIPOC, French

"It needs to be as clear as possible. I want it to be simple and transparent." — Adult 35 and older, Quebec

Indeed, a few participants mentioned they would look for information to better understand the assurance system and label. In addition to the overarching desire to understand sustainability compliance requirements mentioned above, participants also wanted to learn more about the following:

"My question is... what happens if they stop adhering to the standards and what those steps look like." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

"What are the definitions used? What is sustainable? Organic? Certified?" — Adult 35 and older, British Columbia/Territories

When asked how they would like to hear about the assurance system and label, participants suggested, in-store and at the point-of-sale, website(s) (that is, either government or organizations involved in managing the assurance system), traditional media (that is, print, television, radio, billboards, flyer bags, mail), and social media. The majority definitely felt it was important for the Government to raise public awareness and educate Canadians if such an assurance system and label were put in effect.

Interestingly, QR codes were often raised as an effective means of communicating about this assurance system and label, especially in-store/at point-of-sale or on the product. Some, in both age groups, said they would use a QR code in-store, while others said they would use it after purchase at home; some would not do it at all. Also worth noting, some opined on the reach of this communication tool, particularly among older audiences who may not have a smartphone or rely on them in these ways. Regardless, it was generally agreed that a QR code would be a valuable element of triggering access to the desired information.

"I would put a QR code on the product. If something is easier to access, then you have more peace of mind in that information." — Young adult 18 to 34, Atlantic Canada

"It's a good idea to have a QR code on the package or in the store. It's so easy to scan and we do have our phones on us at all times." — Young adult 18 to 34, Prairies

"QR codes are the new norm. Then they can't say they didn't tell you." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

"I like it on the one hand, but it does exclude a whole bunch of people." — Adult 35 and older, Ontario

One participant also suggested having an app for the assurance system.

The research demonstrated that there is a fairly high degree of trust in food produced in Canada, particularly as compared to food imported from elsewhere. The trust participants have in the agriculture and agri-food sector is often tied to how "corporate" they feel the producer is. The smaller the producer is assumed to be, the more trustworthy they are assumed to be.

This trust extends to the sense of sustainability in food production, though, the meaning and use of the term "sustainable" was not universally understood. Perhaps more accurately, sustainability referred to the sense of stewardship of the land; animal welfare; and fair treatment of different people involved in food production including farmers/producers and employees. As a result, discussions about the sustainability of Canada's agriculture and agri-food sector were not always focused on a sense of environmental protection or responsibility.

That said, participants fairly consistently demonstrated a shorthand for assessing environmental sustainability: the more local or small the producer was known or assumed to be, the more environmentally sustainable that product or producer was assumed to be. At the next level below "local" were Canadian products more broadly. While few could say for sure, the tendency was to have confidence that Canadian products could be considered more environmentally sustainable than products arriving from another country of origin. This was generally attributed to two factors: the distance the product must have been transported; and the sense that standard operating procedures for producers in Canada are assumed to be more desirable or responsible than in many other countries from which food is imported.

While many participants said they seek out products that are local and describe this as a habit that results in purchasing products that are produced in a more environmentally sustainable manner, the motivations for doing so did not appear to always be about the desire to purchase more environmentally sustainable products. Quality (meaning flavour and freshness) of products and avoiding some specific issues that people think relates to their health (for example, pesticides, hormones, GMOs) were often cited as more influential than specifically being concerned about environmental impact.

There appeared to be little reliance on existing sustainability-related assurance systems and labels. Unaided recall of assurance systems and labels was limited. The assurance systems and labels that were recalled were not universally accepted as an indication of environmental sustainability. That said, the concept of a common assurance system and label that would assess products on the basis of personally relevant criteria was welcomed if not necessarily meeting a widespread, pent-up demand.

The main concerns that would undermine the appreciation of a common assurance system and label were that such a system would impose unreasonably higher costs on consumers, that smaller farmers/producers would be at a disadvantage, and that larger producers would have more influence. Within the context of exorbitant food prices, described as a major concern, and fear of the economic viability of the local or smaller producers they most respect and value, placing them at any further disadvantage either in their operations or on the store shelves, was identified by some participants as a significant potential drawback. Further exacerbating this sentiment was the assumption by some that larger producers, who are the ones most commonly assumed to be operating in less sustainable and more profitable ways, may be able to more easily afford the cost to undergo the process required to achieve the certification, providing them with an unfair marketing advantage.

The establishment of the set of criteria evaluated and the thresholds set for meeting the standards were seen as key to establishing the value of a common assurance system and label. Most felt that such an assurance system would be best managed by a group of partners that could include farmers/producers, consumers, government, industry, and scientists. The role they have in mind for government was around subsidization, public awareness/education, regulation, oversight, inspection, and enforcement.

Introducing the concept, including demonstrating it consists of the most valid determinants of sustainability, will be key to establishing its credibility and relevance and thus, have any ability to influence purchase decisions. The success would also be dependent upon consumers' perceptions of its impact on the prices of the foods they already prefer and the producers they already trust.

The research included a series of twelve (12) focus groups between January 23 and 25, 2023, with adults aged 18 and older who have joint/sole responsibility for grocery shopping in their household. Five (5) regions of the country were studied: British Columbia/Territories (BC, YK, NT, NU), Prairies (AB, SK, MB), Ontario, Quebec (in French), and Atlantic (NL, NB, NS, PEI). Two groups were conducted in each region, segregated by age (that is, "young adults," 18 to 34 years of age; "adults," 35 years or older). In addition, two groups were conducted with adult consumers identifying as Black, Indigenous, or other Person of Colour (BIPOC) — one in English (with participants from across the country) and one in French (with participants from Ontario and Quebec). Please refer to the recruitment screener in the Appendix B for all relevant screening and qualifications criteria.

For the purposes of this report, the findings of each target audience have been aggregated. However, one of the key takeaways was that perspectives of each audience were quite similar. Unless otherwise noted, findings in this report are common across all audiences; only noteworthy differences are mentioned.

| Group Number | Date | Audience | Region | Time | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT | 7 |

| 2 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Quebec (FR) | 6:00 pm ET | 8 |

| 3 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | BIPOC | English | 7:00 pm ET/8:00 pm AT/8:30 pm NT/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT/4:00 pm PT | 6 |

| 4 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT | 8 |

| 5 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Quebec (FR) | 5:00 pm ET | 7 |

| 6 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET | 4 |

| 7 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT | 7 |

| 8 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT | 7 |

| 9 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | BIPOC | French | 5:00 pm ET/6:00 pm AT/6:30 NT | 7 |

| 10 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET | 8 |

| 11 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT | 6 |

| 12 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT | 6 |

Our fieldwork subcontractor, Quality Response, and their selected suppliers reached out to members of their respective databases first via email and follow-up with telephone calls to pre-qualify participants. This is the approach employed most often. They then conducted telephone recruitment to supplement in each market.

For recruitment in Atlantic Canada and Ontario, Quality Response relied on their own proprietary database of approximately 35,000 Canadians with profiling on a range of attributes including standard personal demographics, household composition, medical background, technology usage, financial services, health and wellness, business profiles, and other relevant criteria. Their database is constantly being updated and replenished. Potential group participants were recruited to their database via mixed-mode: following a proprietary telephone survey, online, referral, social media and print advertising. Initial contact is often made via email or online pre-screening for speed and economies, followed up by personal telephone recruitment and pre-group attendance confirmation.

Quality Response also relied on Metroline and Brookson Research to supplement recruitment in Atlantic Canada and Ontario. Metroline's database includes approximately 4,500 Canadians predominantly in Ontario (non-GTA) and Atlantic Canada. New participants are added to their database via referrals and online advertising. Metroline profiles their database for a variety of characteristics including but not limited to: location; marital status; occupation; income; smoking habits; drinking habits. Respondents from other regions that are not included in their database are recruited via definition by postal code using Canada 411 and cold calling.

Located in Ottawa, ON, Brookson Research's database is comprised of approximately 9,500 individuals in Ottawa and the surrounding area. Data is stored locally and backed up by a local third party provider. New people are added to the database via phone, text, email, and corporate website. The company does twice-yearly drives to refresh the database in English and French. The database is profiled by name, gender, age, contact information, city of residence, education, mother tongue, occupation and history attending market research sessions. Respondents from nearby regions that are not included in their database are defined by postal code/municipality and recruited via cold call, in both official languages unless otherwise specified.

For recruitment in Quebec, Quality Response partnered with MBA Recherche. MBA Recherche's vast database includes approximately 35,000 Canadians across Quebec. They use Google ads, their website, telephone RDD lists, and referrals to recruit new participants. In addition to a variety of demographics, MBA Recherche's profiling includes automobile types, substance use, and mobile phone attributes. Respondents from nearby regions that are not included in their database are recruited via random digit dialing from purchased sample.

For recruitment in Western Canada and the Territories, Quality Response partnered with Walmsley, Pele Research and Qualitative Coordination. Walmsley's database is comprised of approximately 5,500 residents of British Columbia. They rely on referrals and online advertisements to recruit to their database. In addition to a variety of demographics, their database is profiled for: age of children, occupation, spouse's occupation, and health issues. Respondents from nearby regions that are not included in their database are recruited via referral only.

Qualitative Coordination's database contains approximately 5,500 Albertans. Qualitative Coordination uses referrals and online advertisements to find new participants. Their database is not profiled, and new registrants are only asked for their full name, email address, date of birth, and where they reside. Respondents from nearby regions that are not included in their database are recruited via cold calling or referral.

Located in Manitoba, Pele Research's database includes approximately 3,000 Canadians per province across Western Canada (BC, AB, SK, MB). The data is stored locally and is backed up on two separate in-house services. Pele Research profiles their database by name, age, gender, income, education, occupation, and phone number. Respondents from nearby regions that are not included in their database were recruited via referral, largely through past participants.

We understand the nuance of qualitative recruiting and the importance of locating qualified, interested respondents. Quality Response's recruiting is undertaken in strict accordance with the Government of Canada Standards for Qualitative Research.

We relied on two qualified moderators. Given the timeline for the project, using two moderators allowed us to conduct all of the focus groups over the course of one week (3 nights).

Both moderators attended the kick-off night of focus groups. This ensured that both were aware of the flow of the focus groups and were involved in any conversation about potential changes to the discussion guide or flow of conversation for each subsequent night.

In our experience, there is value in using multiple moderators (within reason) as it ensures that no single moderator develops early conclusions. Each moderator takes notes and summarizes their groups after each night. The moderators each provide a debrief on their groups including the functionality of the discussion guide; any issues relating to recruiting, turnout, or technology; and key findings including noting instances where they were unique and where they were similar to previous sessions. Together, they discuss the findings both on an ongoing basis in order to allow for probing of areas that require further investigation in subsequent groups, and before the final results are reported.

It is important to note, when reading the qualitative findings, that qualitative research is a form of scientific, social, policy, and public opinion research. Focus group research is designed to elicit the full range of ideas, attitudes, experiences, and opinions of a selected sample of participants on a defined topic. Because of the small numbers involved, the participants cannot be expected to be thoroughly representative in a statistical sense of the larger population from which they are drawn, and findings cannot reliably be generalized beyond their number.

The following is a glossary of terms used throughout the report to impart the qualitative findings. These phrases are used when groups of participants share a specific point of view. Unless otherwise stated, it should not be taken to mean that the rest of participants disagreed with the point; rather others either did not comment or did not have a strong opinion on the question.

| Group Number | Date | Audience | Region | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT |

| 2 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Quebec (FR) | 6:00 pm ET |

| 3 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | BIPOC | English | 7:00 pm ET/8:00 pm AT/8:30 pm NT/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT/4:00 pm PT |

| 4 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT |

| 5 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Quebec (FR) | 5:00 pm ET |

| 6 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET |

| 7 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT |

| 8 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT |

| 9 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | BIPOC | French | 5:00 pm ET/6:00 pm AT/6:30 NT |

| 10 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET |

| 11 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT |

| 12 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT |

Respondent's name:

Respondent's phone number: (work)

Respondent's phone number: (cell)

Respondent's email:

Interviewer:

Date:

Validated:

Hello/Bonjour, my name is __________ and I'm calling on behalf of Earnscliffe, a national public opinion research firm. We are organizing a series of discussion groups on issues of importance to Canadians, on behalf of the Government of Canada, specifically for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. We are looking for people who would be willing to participate in an online discussion group that will last up to 90 minutes. Up to 8 participants will be taking part and for their time, participants will receive an honorarium of $100. May I continue?

Yes [continue]

No [thank and terminate]

Would you prefer that I continue in English or French? Préférez-vous continuer en français ou en anglais? [if french, continue in french or arrange a call back with french interviewer: Nous vous rappellerons pour mener cette entrevue de recherche en français. Merci. Au revoir].

Participation is voluntary and confidential. We are interested in hearing your opinions; no attempt will be made to sell you anything or change your point of view. All opinions expressed will remain anonymous and views will be grouped together to ensure no particular individual can be identified. But before we invite you to attend, we need to ask you a few questions to ensure that we get a good mix and variety of people. May I ask you a few questions? This will only take about 5 minutes.

Yes [continue]

No [thank and terminate]

Monitoring text:

Read to all: "This call may be monitored or audio taped for quality control and evaluation purposes.

Additional clarification if needed:

1. Do you or any member of your household work for…

[if "yes" to any of the above, thank and terminate]

2. I am going to read you three statements. Please let me know which one most accurately reflects your role in your household.

[preference for a's. If c, thank and terminate]

3. Which province or territory do you live in? [ensure a good mix within region]

4. And in what city, town or community do you reside? [do not read]

5. Could you please tell me which of the following age categories you fall into? Are you...? [ensure a good mix]

6. What is your ethnic background? [do not read] [ensure good mix]

[for groups 11 and 12, none are caucasian. Ensure at least two per group are indigenous.]

7. What is your gender identity? [do not read; ensure a good mix]

8. What is the last level of education that you have completed? [ensure good mix]

9. Which of the following categories best describes your total household income; that is, the total income of all persons in your household combined, before taxes? [read list] [ensure good mix]

This research will require participating in a video call online.

10. Do you have access to a computer, smartphone or tablet with high-speed internet which will allow you to participate in an online discussion group?

11. Does your computer/smartphone/tablet have a camera that will allow you to be visible to the moderator and other participants as part of an online discussion group?

12. Do you have a personal email address that is currently active and available to you?

13. Have you participated in a discussion or focus group before? A discussion group brings together a few people to understand their opinion about a given subject.

14. When was the last time you attended a discussion or focus group?

15. How many of these sessions have you attended in the last five years?

16. Participants in discussion groups are asked to voice their opinions and thoughts. How comfortable are you in voicing your opinions in front of others? Are you…? [read list]

17. Sometimes participants are asked to read text, review images, or type out answers during the discussion. Is there any reason why you could not participate?

18. Is there anything we could do to ensure that you can participate?

19. What specifically? [open end]

[interviewer to note for potential one-on-one interview]

20. Based on your responses, it looks like you have the profile we are looking for. I would like to invite you to participate in a small group discussion, called an online focus group, we are conducting at [time], on [date]

It will last up to up to 90 minutes and you will receive $100 as a thank you for your time. Would you be willing to attend?

Now I have a few questions that relate to privacy, your personal information, and the research process. We will need your consent on a few issues that enable us to conduct our research. As I run through these questions, please feel free to ask me any questions you would like clarified.

P1. First, we will be providing a list of respondents' first names and profiles (screener responses) to the moderator. Do we have your permission to do this? I assure you it will be kept strictly confidential.

We need to provide the first names and background of the people participating because only the individuals invited are allowed in the session and this information is necessary for verification purposes. Please be assured that this information will be kept strictly confidential. [go to p1a]

P1A. Now that I've explained this, do I have your permission to provide your first name and profile?

P2. A recording of the group session will be produced for research purposes. The recordings will be used by the research professional to assist in preparing a report on the research findings and may be used by the Government of Canada for internal reporting purposes.

Do you agree to be recorded for research and reporting purposes only?

It is necessary for the research process for us to record the session as the researchers need this material to complete the report.

P2A. Now that I've explained this, do I have your permission for recording?

P3. It is standard qualitative procedure to invite clients, in this case, Government of Canada employees, to observe the groups online. They will be there simply to hear your opinions firsthand although they may take their own notes and confer with the moderator on occasion to discuss whether there are any additional questions to ask the group.

Do you agree to be observed by Government of Canada employees?

Wonderful, you qualify to participate in one of our discussion sessions. As I mentioned earlier, the group discussion will take place on [date] at [time] for up to 90 minutes.

| Group Number | Date | Audience | Region | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT |

| 2 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Quebec (FR) | 6:00 pm ET |

| 3 | Monday, January 23, 2023 | BIPOC | English | 7:00 pm ET/8:00 pm AT/8:30 pm NT/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT/4:00 pm PT |

| 4 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Atlantic Canada (EN) | 4:00 pm ET/5:00 pm AT/5:30 NT |

| 5 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Quebec (FR) | 5:00 pm ET |

| 6 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET |

| 7 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT |

| 8 | Tuesday, January 24, 2023 | Young adults (18 to 34) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT |

| 9 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | BIPOC | French | 5:00 pm ET/6:00 pm AT/6:30 NT |

| 10 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Ontario (EN) | 6:00 pm ET |

| 11 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | Prairies (EN) | 7:00 pm ET/6:00 pm CT/5:00 pm MT |

| 12 | Wednesday, January 25, 2023 | Adults (35 and older) | BC/Territories (EN) | 8:00 pm ET/7:00 pm CT/6:00 pm MT/5:00 pm PT |

Can I confirm your email address so that we can send you the link to the online discussion group?

We ask that you login a few minutes early to be sure you are able to connect and to test your sound (speaker and microphone). If you require glasses for reading, please make sure you have them handy as well.

As we are only inviting a small number of people, your participation is very important to us. If for some reason you are unable to attend, please call us so that we may get someone to replace you. You can reach us at [insert phone number] at our office. Please ask for [name]. Someone will call you in the days leading up to the discussion to remind you.

So that we can call you to remind you about the discussion group or contact you should there be any changes, can you please confirm your name and contact information for me?

First name:

Last name:

Email:

Daytime phone number:

Evening phone number:

If the respondent refuses to give his/her first or last name, email or phone number please assure them that this information will be kept strictly confidential in accordance with the privacy law and that it is used strictly to contact them to confirm their attendance and to inform them of any changes to the discussion group. If they still refuse thank and terminate.

Section time: 10 min / Cumulative time: 10 min

Moderator introduces themselves and their role: role of moderator is to ask questions, make sure everyone has a chance to express themselves, keep track of the time, be objective/no special interest.

Moderator will go around the table and ask participants to introduce themselves.

Introduction of participants: To get started, please tell us your first name, who lives in your household [that is, whether you live with someone including children (number and ages of children)], and your role in grocery shopping and/or meal preparation.

Rationale 1: The objective of this section is to understand overall, unaided, perceptions of Canada's agriculture industry. This serves as a warm-up and context setting section that helps frame the conversation.

Rationale 2: To understand overall public trust in the agriculture and agri-food sector, including perceived public trust challenges, solutions, and how (if at all) they relate to assurance systems/labels.

To begin, I would like to ask you a few questions and would ask that you use the chat box to record your answer. You can send your response to 'everyone in the meeting'. If you're having trouble using the chat box function, you can provide your response verbally.

Public trust in the agricultural sector refers to the confidence Canadians have in the way their food is produced, processed, labelled, or packaged.

Rationale: To understand overall views on environmental sustainability and use in food purchasing decisions.

Let's focus on environmental sustainability related to food produced in Canada.

Rationale: To understand participants' unaided and aided views of assurance systems/labels.

I would like to talk about how environmental sustainability is shown on food labels.

For the purposes of our discussion tonight, I want to show you a description of assurance labels so that we are all on the same page.

An assurance label tells you a product has been produced (grown, manufactured, or packaged) in a specific way. The product must meet certain requirements to use the label.

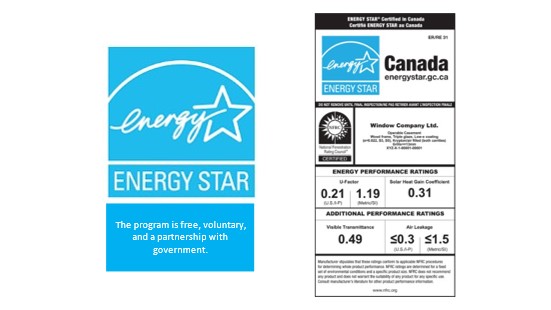

An example in Canada is the Energy Star program. It marks products that have been manufactured to have a high energy efficiency. [show label and a diagram indicating there is a certification system behind it].

Now let's think about assurance labels and food. This could be when the food is grown or made using specific environmental requirements or standards, or the food is certified as being made in a specific way.

[now show food-related assurance label examples: Blue cow, Fair Trade Canada and Marine Stewardship Council, mention all have systems behind them].

Having heard this description and seen these examples…

Now, let's think more about environmental sustainability and food assurance labels.

Rationale: To understand participants' purchase behaviours and role assurance labels play in those decisions.

Let's go back to thinking about environmental sustainability in food purchasing decisions and food assurance labels.

Rationale: To understand participants' views related to a common assurance label their hopes, and desires for that system, and who they would trust to manage and certify that label and the standards behind it.

In some countries, they have a common label and logo for a wide range of assurance labelling programs (for example, food safety standards for a variety of products, environmental sustainability, and animal welfare). These assurance labelling programs have been created by the agriculture industry to help consumers to easily identify the label and know the standards behind it.

[show red tractor example including multiple labels and explain how it includes a number of labels for different programs Our Logos | Red Tractor]

[if time permits]

Now let's return to environmental sustainability.

Rationale: To understand participants information needs and where they would turn for information about such a system.

[moderator to request additional questions are sent via the chat box directly to the moderator and probe on any additional areas of interest]

This concludes what we needed to cover tonight.

We really appreciate you taking the time to share your views. Your input is very important.

Assurance labels examples 1:

Composed of two images. The first is the Energy Star stylized logo with a star graphic and text: The program is free, voluntary, and a partnership with government.

The second image is an example of an appliance label for a window company that qualifies for the Energy Star program. The label includes a smaller Energy Star logo and the text "Canada energystar.gc.ca" followed by a number of energy performance metrics, such as U-Factor, Solar Heat Gain, Visible Transmittance, and Air Leakage that certify the product meets the criteria to qualify for the Energy Star program.

Assurance labels examples 2:

There are three examples of food product assurance labels. The first label is the logo of the Dairy Farmers of Canada. It features an illustrated cow with a maple leaf overlayed on the body of the cow, standing on soil, with the text wordmark "Dairy Farmers of Canada" underneath it. The second label is from Fairtrade Canada. It features a circle with a stylized figure inside and text underneath. The graphic is meant to represent a person holding their right arm up between the green earth and the blue sky. The text reads "Fairtrade Canada ®." The third label is from Marine Stewardship Council Certified Sustainable Seafood. The label features text and a graphic of a fish inside a circle. The text reads "Certified Sustainable Seafood MSC www.msc.org" TM.

Assurance labels example 3:

There are seven "Red Tractor" labels, each representing different certified standards. The labels use different colours as another way to differentiate the standards. All seven labels feature a logo of a tractor sitting atop a check mark. The back wheel of the tractor has a heart shape in place of a wheel hub, and there is a partial rendering of the British Union Jack flag, with wording below the label to describe the standard. All seven labels have the words "Red Tractor" above the tractor illustration, and different text below it. The main image has the text "Certified Standards," the others have the following wording; certified milk, certified pork, certified beef, certified lamb, enhanced welfare and free range.