CFIA Public Opinion Research for the Food Business Line 2023 to 2024

Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Final report

March 2024

Prepared for:

Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Supplier name: Quorus Consulting Group Inc.

Contract award date: December 15, 2023

Delivery date: March 2024

Contract amount (incl. HST): $261,052.60

Contract number: CW2341947

Public opinion research number: POR- 103-23

For more information, please contact:

Ce rapport est aussi disponible en français.

Copyright Page

CFIA Public Opinion Research for the Food Business Line 2023 to 2024

Final report

Prepared for the Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Supplier name: Quorus Consulting Group Inc.

March 2024

This public opinion research report presents the results of quantitative and qualitative research conducted by Quorus Consulting Group Inc. on behalf of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency in February and March 2024. The research involved eight online focus groups with food industry representatives, ten online focus groups with Canadian consumers aged 18 and older, 850 telephone surveys with individuals with responsibility for food safety and quality control at their place of business, and 1,500 online surveys with Canadian consumers 18 and older.

Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre : Recherche sur l'opinion publique pour le secteur alimentaire 2023 à 2024

This publication may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes only. Prior written permission must be obtained from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. For more information on this report, please contact the Canadian Food Inspection Agency at: Information@inspection.gc.ca or at:

Canadian Food Inspection Agency

1400 Merivale Road

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0Y9

Catalogue number:

A104-631/1-2024E-PDF

International standard book number (ISBN):

978-0-660-70116-5

Related publications (registration number: POR- 103-23):

Catalogue number: A104-631/1-2024F-PDF (final report in French)

ISBN: 978-0-660-70117-2

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2024

Political neutrality certification

I hereby certify as senior officer of Quorus Consulting Group Inc. that the deliverables fully comply with the Government of Canada political neutrality requirements outlined in the Policy on Communications and Federal Identity and the Directive on the Management of Communications - Appendix C.

Specifically, the deliverables do not include information on electoral voting intentions, political party preferences, standings with the electorate or ratings of the performance of a political party or its leaders.

Signed:

March 20, 2024 Rick Nadeau, President Quorus Consulting Group Inc.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Research purpose and objectives

- Detailed results

- Research purpose and objectives

- Qualitative research results – focus groups with consumers

- Qualitative research results – focus groups with food businesses

- Quantitative research results – food safety consumer survey

- Quantitative research results – food business survey

- Methodology

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Recruitment screener for focus groups with consumers

- Appendix B: Recruitment screener for focus groups with food businesses

- Appendix C: Moderation guide for focus groups with consumers

- Appendix D: Moderation guide for focus groups with food businesses

- Appendix E: Questionnaire for telephone surveys with food businesses

- Appendix F: Questionnaire for online surveys with Canadians

Executive Summary

Research purpose and objectives

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has a mandate to verify food sold in Canada is safe and accurately represented. The CFIA achieves this through enforcement of Canada’s federal food legislation, including the Safe Food for Canadians Act (SFCA) and its regulations (SFCR) which introduced new requirements for food businesses as of January 15, 2019.

The CFIA also develops and delivers programs and services designed to protect Canadians from preventable food safety hazards, to ensure that food safety emergencies are effectively managed, food is accurately represented, and to ensure that the public is aware of—and contributes to—food safety. The SFCR provide clear and consistent rules for food commodities so that consumers can be confident that food on grocery shelves is safe to eat, whether it is produced in Canada or abroad. The regulations also help get unsafe food off the shelves faster by requiring businesses that import or prepare food for export or interprovincial trade to trace their food back to their supplier and forward to whom they sold their products.

Canadian law prohibits the labelling, packaging, treating, processing, selling or advertising of any food in a manner that is false, misleading or deceptive to consumers. Food fraud can mislead consumers and is also a food safety issue (for example, if products contain undeclared allergens). The CFIA works to raise awareness of and protect consumers from food misrepresentation by conducting inspections, analyzing food samples and taking enforcement action.

The objective of this research is to gain a better understanding of industry awareness, motivations, perceptions and attitudes about:

The various roles and responsibilities within the food safety system, in particular to measure the level of awareness of their own responsibilities in the system;

Federal food regulations as they apply to online sales and importing;

Resource needs and barriers to complying with regulatory requirements, to identify root causes of non-compliance and support development and implementation of compliance promotion, communications, and support service activities;

Current services and expectations on future services and programs, such as My CFIA;

Specific messaging, including compliance promotion tools and communications products;

The effectiveness and satisfaction of the SFCR communications and related communications from various services, such as My CFIA and Ask CFIA;

How requirements change for businesses may vary depending on demographic characteristics of ownership or clientele;

Satisfaction with guidance received from Ask CFIA and rating of overall experience in using the service; and,

Industry’s opinion on using third-party verification systems.

Additionally, the research will aim to gain a better understanding of the following among consumers:

Awareness and understanding of food safety and food fraud, and how the CFIA addresses them;

Awareness of the CFIA’s online food concern reporting tool;

Trust that CFIA takes enforcement action to protect consumers from food fraud;

Habits and concerns about food safety;

Habits and concerns about best-before dates;

Public trust that fish is accurately labelled and safe to eat;

Sources of information on food safety and food fraud;

Perceptions and concerns about food fraud;

Awareness and effectiveness of CFIA communications regarding food fraud; and,

Awareness and understanding of CFIA transparency regarding food fraud enforcement activities.

Methodology

The research study consisted of the following four phases:

Phase 1: Online focus groups with Canadian adults (aged 18+)

Phase 2: Online focus groups with representatives of Canadian food businesses

Phase 3: Telephone survey with representatives of Canadian food businesses

Phase 4: Online survey with Canadian households

Qualitative research results – focus groups with consumers

This portion of the research consisted of ten online focus groups with Canadians aged 18+ (consumers) which Quorus completed between February 1 and February 10, 2024.

Overall views on and experiences with food fraud

Defining food fraud

To kick-off the focus groups with consumers, participants were shown the sentence, “Food fraud occurs when food is misrepresented,” and asked to provide some examples of what they felt would constitute food fraud.

Participants commonly suggested inaccuracies with product weight or misleading labelling such as those labelled as “natural” or “healthy” but contain artificial ingredients, fish products that are farmed, but do not specify origin on package, or meat that is mechanically tenderized but does not say so on package. A few mentioned products being falsely labelled as “organic” “free-range”, or fish being labelled incorrectly.

Sources of information on food fraud

Some participants recalled seeing examples of food fraud on social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or Reddit, or on the news, documentaries as well as from friends and family.

For the most part, participants did not actively look for information on food fraud but rather came across news articles or posts on the topic.

Level of concern with food fraud

Most participants were not overly concerned about encountering food fraud when purchasing food from grocery stores. Those who were more concerned with food fraud tended to be those with a food allergy or dietary restriction in their household as well as those who were health conscious. These participants tended to pay closer attention to ingredient lists and nutrition labels to ensure that the products they are buying are suitable for their dietary needs.

Participants suspected animal products to be most susceptible to food fraud, particularly when it comes to labels such as “organic”, “natural”, “free-range”, “grass-fed”, “triple A” or “halal”. Some had similar concerns regarding “organic” labelling on fruits, vegetables or packaged foods.

Some also felt that processed or packaged foods may be subject to food fraud as it would be easier for companies to add cheaper ingredients as a way to save costs and consumers likely would not notice.

When specifically asked about fish sold in Canada, most said that they trusted that it is for the most part, properly labelled as they had no reason to believe otherwise.

Some felt that fraud would be more likely to occur in packaged fish such as canned tuna or fish sticks, which may use a mix of less expensive fish rather than the type of fish listed on the package and consumers would be less likely to notice the discrepancy.

A majority of participants agreed that the fish sold in Canada is safe to eat. Rather than concerns about food fraud, concerns about safety of fish mainly pertained to its freshness.

Personal experiences with food fraud

Overall, very few participants had personally experienced food fraud. That said, some admitted that they might not know if they had encountered or consumed a product that was fraudulent.

As a result of suspected food fraud, some participants said they did not buy the product again, did not consume the product out of concern for potential allergens, returned the product to the store, or emailed the company. None of the participants indicated having reported their concern with a government agency such as the CFIA.

If they were to encounter food fraud in the future, many participants suggested they might return the product to the store they purchased it from to try to get refunded, especially if it was an expensive item. Others would try to contact the supplier/manufacturer directly.

If the fraud resulted in a health consequence such as food poisoning or an allergic reaction from an undisclosed ingredient, participants would be much more likely to take action. In these cases, a couple of participants suggested that they may look up the government department that handles these complaints.

Views on how food fraud is managed in Canada

For the most part, participants felt that food fraud is well managed in Canada. As well, there was a high level of confidence that food in Canada is safe to eat. This sentiment came from the fact that in most groups, none or very few participants had experienced food fraud, or knew somebody else who had. Additionally, a few mentioned that when food safety issues occurred, as seen through food recalls, actions are quickly taken to inform Canadians and pull these products from shelves, which gave them reassurance.

Most assumed that there is a government agency responsible for managing food safety, however only a few mentioned the CFIA organically. There was some general agreement that there should be more awareness of the topic of food fraud, how the government is managing the issue as well as what to do if you encounter it. Some mentioned that they would be unsure where to report food safety issues or food fraud if they were to encounter it.

Awareness of CFIA’s involvement in food fraud

Participants were informed that the CFIA is responsible for regulating food in Canada and verifying that companies are complying with the federal food rules. While many had heard of the CFIA before, very few had ever thought about contacting the CFIA when they encountered food fraud or a similar food safety issue. Instead, they typically thought of contacting the store or the manufacturer.

Many were apprehensive about contacting the CFIA regarding food fraud with concerns that it would probably take awhile to get a response, or it might not be worth the effort, especially if it was just a mislabelling issue rather than a food safety concern. However, if the food fraud was to result in a health consequence, more would consider contacting the CFIA.

With that said, some felt that it was good to know that the CFIA could be a contact for food fraud concerns, as some explained they would trust a government department or agency to do more to look into the actual issue than the store where the product was sold or the manufacturer.

When shown a screenshot of the CFIA’s online food concern reporting tool, very few had seen or heard about it before.

Views on food recalls

Participants varied with their concern regarding food recalls, with some on high alert for recalls while others do not pay much attention to them.

Participants typically learn of food recalls from the news, social media, from signage or information boards in grocery stores, or from friends and family. A handful of participants said they received email alerts.

Only a small number of participants were aware of email alerts prior to the discussion. When specifically asked about this type of notification, interest in a subscription service to receive recall email notifications from an agency like CFIA was quite high.

Reactions to CFIA messaging regarding food fraud

Reactions to a social media post concept

In order to gain feedback on CFIA messaging regarding food fraud, a social media post was tested with participants. Participants were informed that for legal reasons, the post could not name the company that was being discussed.

Some participants felt that the post was good as it could help raise awareness of the topic of food fraud and remind Canadians that the CFIA is doing investigations and holding companies accountable. Others said that they would probably scroll past this post if they saw it on social media as it does not really affect them or they did not deem this misrepresentation to be a “big deal”.

Many were concerned about the fact that the company could not legally be named as they felt that it does not allow Canadians to make informed decisions about their purchases. Some also felt that if the company were named, it would hold that, and probably other companies, more accountable to follow regulations in the future.

Reactions to CFIA messaging

Participants were also asked to provide feedback on the following series of statements which the CFIA could use in some of its communications with Canadians:

Overall, many felt that these statements were reassuring and alleviated some concerns and worries they had. Some would like to see more information about how the investigation process works as well as what the regulations are in general.

Some felt that the statements were vague and should include statistics or facts to make the message more believable or reassuring.

Overall views on and experiences with “best before” dates

An important research objective was to better understand Canadians’ views and use of “best before” dates.

Many were confident that they understood the difference between an expiration date and a “best before” date on food products. A few were less confident in the difference between these two dates with some admitting that they will throw food away once it is past the “best before” date.

To make sure all participants were on the same page, definitions were provided:

After hearing these definitions, some admitted that they did not realize the difference between these dates.

Most pay attention to “best before” dates at the grocery store, particularly when it comes to meat or dairy products (particularly milk). These participants typically wanted to purchase items that will stay fresh for longer once they bring it home rather than because of food safety concerns. A few said that they will purchase discounted food that is close to the “best before” date with intentions to use it right away or freeze it.

Most participants were more lenient on best “before dates” when it comes to food products in their home, especially pantry items. However, they remain cautious with certain items such as meat, fish and milk. These participants explained that they will check for signs of spoilage to determine freshness and decide whether they should consume it.

When the topic of removing “best before” dates from food items was probed, most were opposed. Participants generally felt that even though “best before” dates should not necessarily be used as a firm date, they are still beneficial as a guideline, especially when it comes to items such as meat, fish and dairy products. Participants would be less concerned about the removal of “best before” dates on items such as spices or non-perishable items.

There were concerns that without “best before” dates, items might sit on the shelves at stores for long periods of time and it might be difficult to know if an item has already spoiled before purchasing it.

While several felt that removing “best before” dates would likely reduce food waste, they suggested that instead there should be more awareness on the difference between an expiry date and “best before” date so that consumers would be encouraged to inspect items that are past their “best before” date rather than just throwing them out.

Qualitative research results – focus groups with food businesses

This portion of the research consisted of eight online focus groups with food business representatives which Quorus completed between February 14 and February 21, 2024.

General attitudes towards and awareness of food regulation and compliance

Perceptions of Canada’s approach to food regulation

For the most part, food regulation in Canada was described as strict but fair, offering solid consumer protection. From a business perspective, some felt it was somewhat demanding, especially when it came to paperwork and labelling. As well, a number of participants spoke of regulations being difficult to understand or implement for new businesses in particular.

While some said the CFIA was easy to get in touch with, others said that it was not always easy to get the answers they were looking for regarding regulations. Some also felt that even when given answers, they did not feel that the CFIA was “on their team” or specific enough with their guidance to help them solve an issue.

Outcome-based regulations

Familiarity with the term “outcome-based regulations” was quite low. However, many participants could guess fairly accurately what was meant by the term.

Overall, many felt that from a business perspective, this could sometimes make things difficult, since it could be trial-and-error when trying to either start a new business, when trying to comply with new regulations or when fixing issues of non-compliance. This was particularly said by smaller businesses, since they did not have dedicated staff to deal with regulations. As well, small business owners in particular said that it would have been easier with more “how to” supports from the CFIA (for example, guidance or checklists).

On the other hand, some did feel it made sense to put the responsibility on businesses to understand their own processes and how they can best comply with regulations, especially for those who had been in the industry for a long time. It was also said to signal respect for industry and an acknowledgement that professionals in their various industries would know well (or best) how to achieve outcomes, and that the regulator is open to listening, learning and work together in a collaborative way.

There was some agreement that if food products are safe, they by definition meet regulatory requirements. On the other hand, some countered that there was more to meeting requirements than only food safety (for example, labelling, traceability).

Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SFCR)

Familiarity with SFCR

Not everyone was familiar with the fact that the CFIA’s regulations were called the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SFCR). Familiarity with these regulations was noticeably higher among participants whose main role was food safety and/or quality control and lower among businesses whose primary activity is retail. Among those who were familiar with the SFCR, most recognized that these regulations are outcome-based although, as noted above, not everyone agreed that they should be.

When asked about key safety requirements in the SFCR, a few participants could name specific elements of it, such as traceability, pest control, building and/or equipment maintenance, other preventive controls, licensing, hazards planning, labeling, and packaging. When listed, many were familiar with these elements, but they often referred to their own specific procedures and standards rather than to the larger umbrella terms or regulations they might fall under.

For the most part participants said it is relatively easy to comply with food regulations in Canada. In some cases, participants say they exceed the CFIA standards because they feel those are the minimum requirements and they want to do better.

In terms of compliance challenges, specific points were raised around interactions with the CFIA. More specifically, participants would refer to issues working with or contacting CFIA, for example not getting answers as quickly as they had hoped, getting conflicting opinions or advice depending on who at CFIA they spoke to, feeling vulnerable or unsure as a business when trying to comply or even knowing if they are on the right path to compliance, or unclarity about expectations more generally.

Other types of compliance challenges raised in these groups included not always knowing whether or not suppliers closely followed regulations, trying to figure out and comply with inter-provincial trade regulations, labelling, expiry dates, and excessive paperwork.

Participants were also asked what explains their successes in complying with food regulations. Many businesses explained that Canadian products are held to high standards and are counted among the best in the world, which in turn opens up a lot of international markets for them. Traceability and detailed record-keeping by them as well as by all parts of the supply chain were also said to help them meet regulations. Some also attribute some of their success in complying to their good relationship with the CFIA in general and also to inspectors being helpful.

CFIA’s role in food safety regulation

For the most part, CFIA’s role is generally understood to be that of regulator for the Canadian food industry, and to ensure the safety of the food Canadians eat. It was also mentioned that one of its roles is to ensure that uniform standards are met across the country and throughout the whole supply chain.

In terms of helping businesses comply with food regulations in Canada, those who felt that the CFIA had in fact been helpful to them in the past considered the CFIA a partner. These participants often spoke about the education aspect – the CFIA helping them to find information or directly sending them information they required regarding the regulations, often particularly when starting their business.

“Best before” dates

Opinions about “best before” dates generally reflect that they serve an important role in food safety where they are required, particularly from a consumer perspective.

When participants said it played some role in their business, the most-often mentioned context was for inventory control. “Best before” dates were also seen as a way to protect businesses from consumer complaints. It also makes some feel like it represents their guarantee to customers, that their product will still be fresh or good for consumption until that date, acting in a way as a quality control stamp (rather than only a food safety measure).

There is a general sense that “best before” dates are important for consumers as well as for businesses, and that doing away with them would lead to, at best, confusion, and, at worse, consumer safety being compromised. Again, it was also brought up that “best before” dates are important for liability purposes, and that without them, businesses could more easily get in trouble (or be asked for refunds, etc.) if consumers get sick when eating bad food. There was also some sense that removing “best before” dates just “didn’t feel right” for businesses.

Food fraud

In order to level-set common understanding, food fraud was explained to participants first, as follows:

Very few participants had directly experienced or been impacted by food fraud, and even fewer had received a consumer complaint about food fraud. Hypothetically, if they would have been accused of or found to have committed food fraud, participants generally said they would get to the bottom of it and rectify it as soon as they could, first by investigating their own processes and procedures, and then by moving back through the supply chain and ask questions to find the root cause.

Preventative controls to avoid food fraud they have in place for the most part include what participants call their standard quality control procedures, for example weighing products, checking them visually or otherwise, and carefully checking the labels of anything they use to make their end products. Some also conduct random testing on products they receive from their suppliers.

However, for many participants it was difficult to pin-point specific controls they have in place to prevent being impacted by food fraud specifically. Those who use suppliers of raw materials often explain how these are solid, trusting relationships and that they carefully vet new suppliers, and get to know them. Many also ensure their suppliers have needed certifications and proper traceability procedures in place. As well, there is generally a strong level of trust in the Canadian food safety regulatory system, which leads to businesses trusting that if products have made it to them through this system, it is meeting the standard and they can in turn trust the label.

Responses were mixed when asked whether they would report suspected food fraud in their industry to the CFIA. While some would not, others said they might, but likely only after speaking to the suspected company directly or going through an industry association to report it first. Some participants mentioned that they would be more likely to report it if it could be done anonymously. It was also mentioned that it would depend on the “level of proof” they had. The primary motivation for wanting to report suspected fraud is if the fraud results in a competitive advantage for the accused. As well, there was concern for repercussions on the entire food category or industry vertical if fraud is not appropriately addressed.

Many participants agreed with the CFIA publishing more information about misrepresented products identified through inspection activities. They felt that the type of information published should include details of what rules were broken, how it happened, what the impact on consumers or food safety was, and how it was detected. Most participants felt that in order to be fully transparent, publishing the product name, brand name and/or company name that was found to have committed food fraud should be part of the information made public.

However, some said that this was their perspective as a consumer, but that from a business perspective, they felt that the CFIA should carefully weigh the impacts this could have on a company, and that this should only be made public if repeated warnings were not heeded or if food fraud was a trend or an ongoing issue with a brand or company. There also had to be solid proof of who perpetrated it and that it was purposeful, systemic or malicious, and not the result of accidental human error or a simple one-time oversight. Some also mentioned that the CFIA should also be transparent when it comes to companies rectifying the problem and close the loop by publishing that information as well.

Among participants who sell fish or seafood products, there is also a high level of confidence that that the fish and seafood products they sell are properly labelled for the type of fish when it comes to the common name. If food fraud were to happen in this category, some assumed that it would be perpetrated at or close to the source before the product is imported into Canada. Others believe the fraud would be committed at the store level.

CFIA tools

A variety of CFIA virtual tools were shown to participants in order explore familiarity and collect feedback.

CFIA website

Several participants said they had used the CFIA website when looking for information related to their business.

Of those who had used the website, feedback was mostly positive. These participants were generally able to find what they needed on the website. Some commented on the ease of finding information through the menu options. When asked to provide other feedback, some suggested that recall information could be more noticeable and some also suggested that the CFIA could offer more resources which business owners or managers could use to show employees.

Participants were generally not familiar with the virtual assistant and were unable to offer feedback.

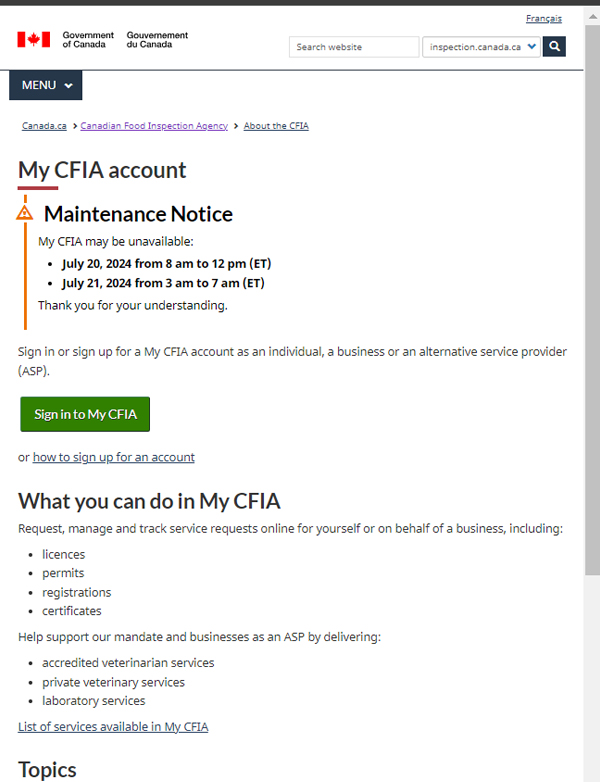

My CFIA

Only a few participants had used My CFIA in the past and awareness of the service was generally quite low among the others.

Of the few who had used this service, most felt it was user-friendly and convenient when they needed to renew or amend a licence. A couple felt that it was challenging to figure out at first, but became easier and that when they had questions, CFIA employees were helpful.

Ask CFIA

A handful of participants had reached out to the CFIA through the website, however several explained that their business has a contact or inspector that they will contact instead if they have questions.

Very few were aware of the Ask CFIA service, although a couple said it looked familiar and that they think they may have used it in the past to ask questions.

Effectiveness of SFCR communications

Few participants received communications or recalled receiving such communications directly from CFIA. For the most part, communications about regulations came from third parties such as newsletters from industry associations or informal communications with others within their industry.

Receiving information from industry associations seemed to be a preference for some who felt that communication coming directly from the CFIA may get lost, or likely would not be very tailored to them. There would be interest in receiving more communications from the CFIA if it could be divided by industry so that businesses can look for the relevant information.

When asked how communications could be improved, some liked the idea of having a contact at the CFIA that they can quickly reach out to for information as needed. Similarly, a few felt that the business relationship with the CFIA should feel more like a partnership where the business can work together with their CFIA contact along the way rather than the relationship being more unilateral.

It was also suggested that there is a lack of bilingual services and support in regions where French is a minority language.

Qualitative research disclaimer

Quantitative research results – online survey with Canadian households

Familiarity with the CFIA

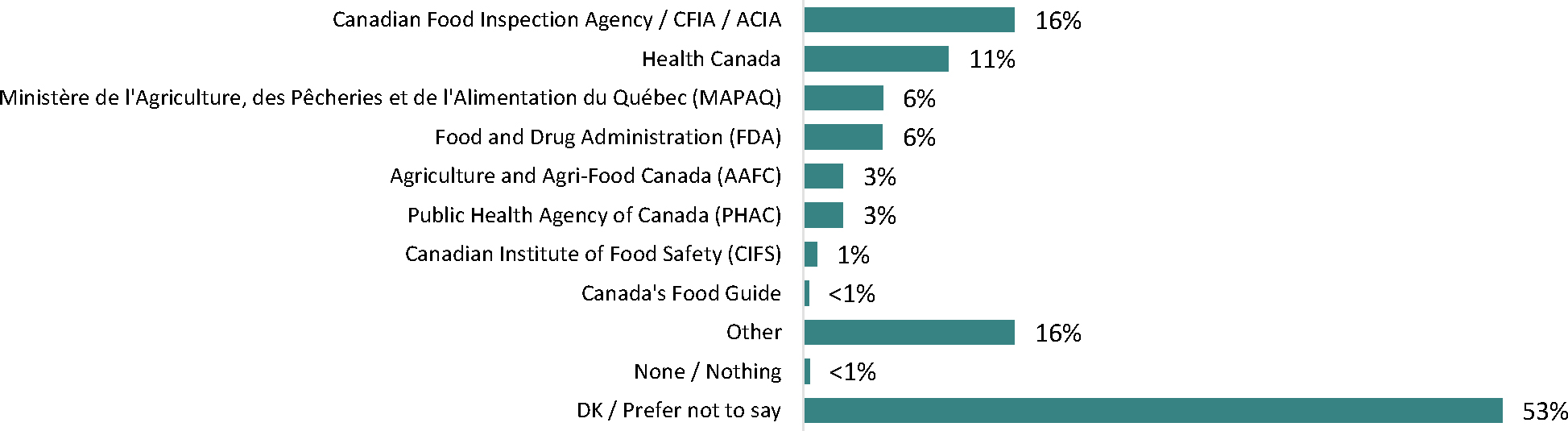

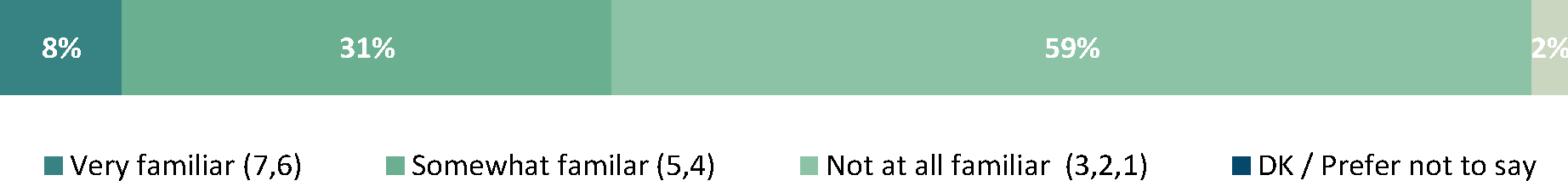

Unaided, over half of respondents were unsure of any organizations in Canada that are dedicated to food safety (53%). More than 1 in 10 respondents thought of the CFIA (16%), followed by Health Canada (11%), Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec (6%), and the Food and Drug Administration (6%).

Roughly 3 in 5 respondents (59%) were not familiar with the activities of the CFIA while nearly a third (31%) were somewhat familiar. A smaller proportion reported being very familiar with the activities of the CFIA (8%).

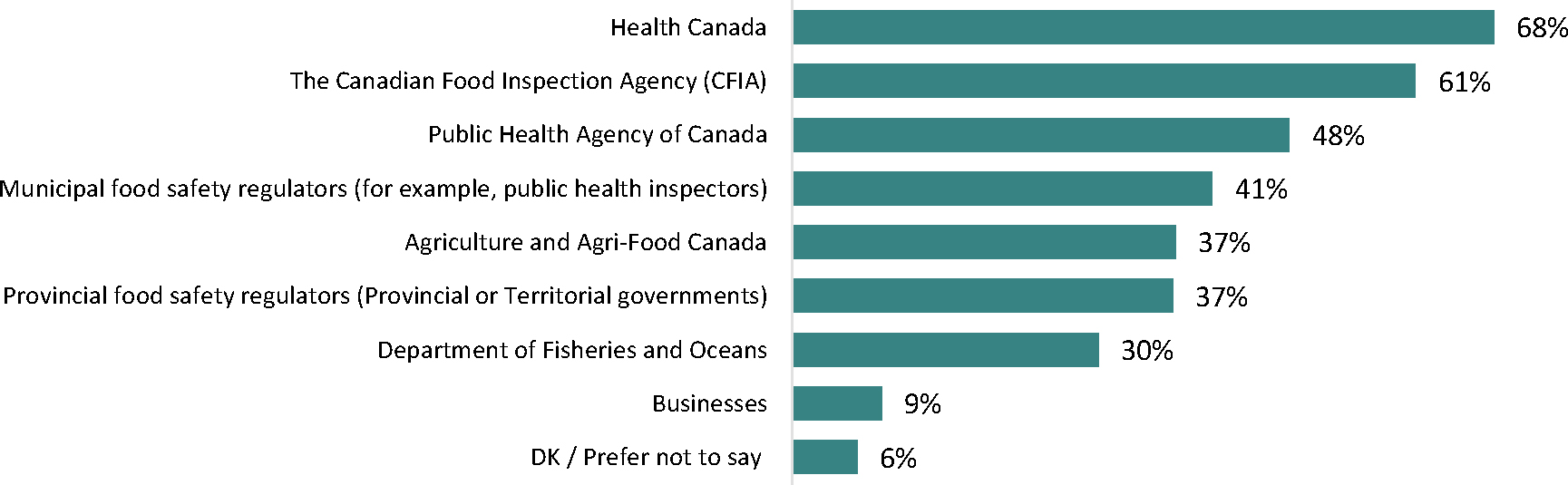

When provided a list of organizations and asked which ones they think of when it comes to food safety in Canada, the most common organization selected was Health Canada (68%) followed by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (61%) and then the Public Health Agency of Canada (48%).

When presented with a list of food safety related roles, 62% believed that the CFIA was involved in checking food products being imported into the country. A similar proportion believed they were involved in conducting food safety investigations (59%), issuing food recalls (59%), and taking enforcement action against food producers who aren’t following Canada’s laws (57%).

Far fewer believed that the CFIA play the following types of roles:

is involved when it comes to live animals being exported from Canada to other countries to be consumed as food (35%).

handles complaints that a restaurant has a dirty kitchen (26%)

handles complaints when a person gets food poisoning from cooking and eating undercooked meat (16%).

Contact with the CFIA

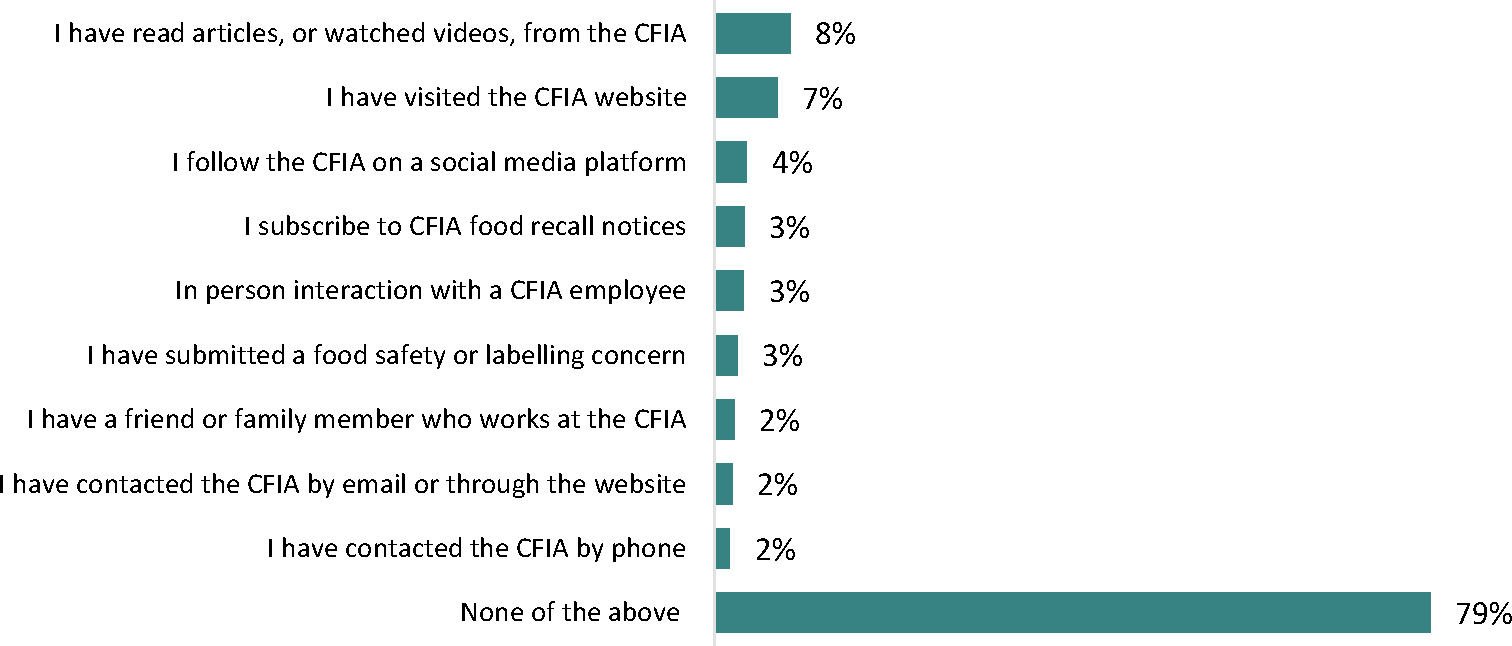

Most respondents had not had any interactions with the CFIA (79%). Nearly 1 in 10 had read articles or watched videos from the CFIA (8%) or visited the CFIA website (7%).

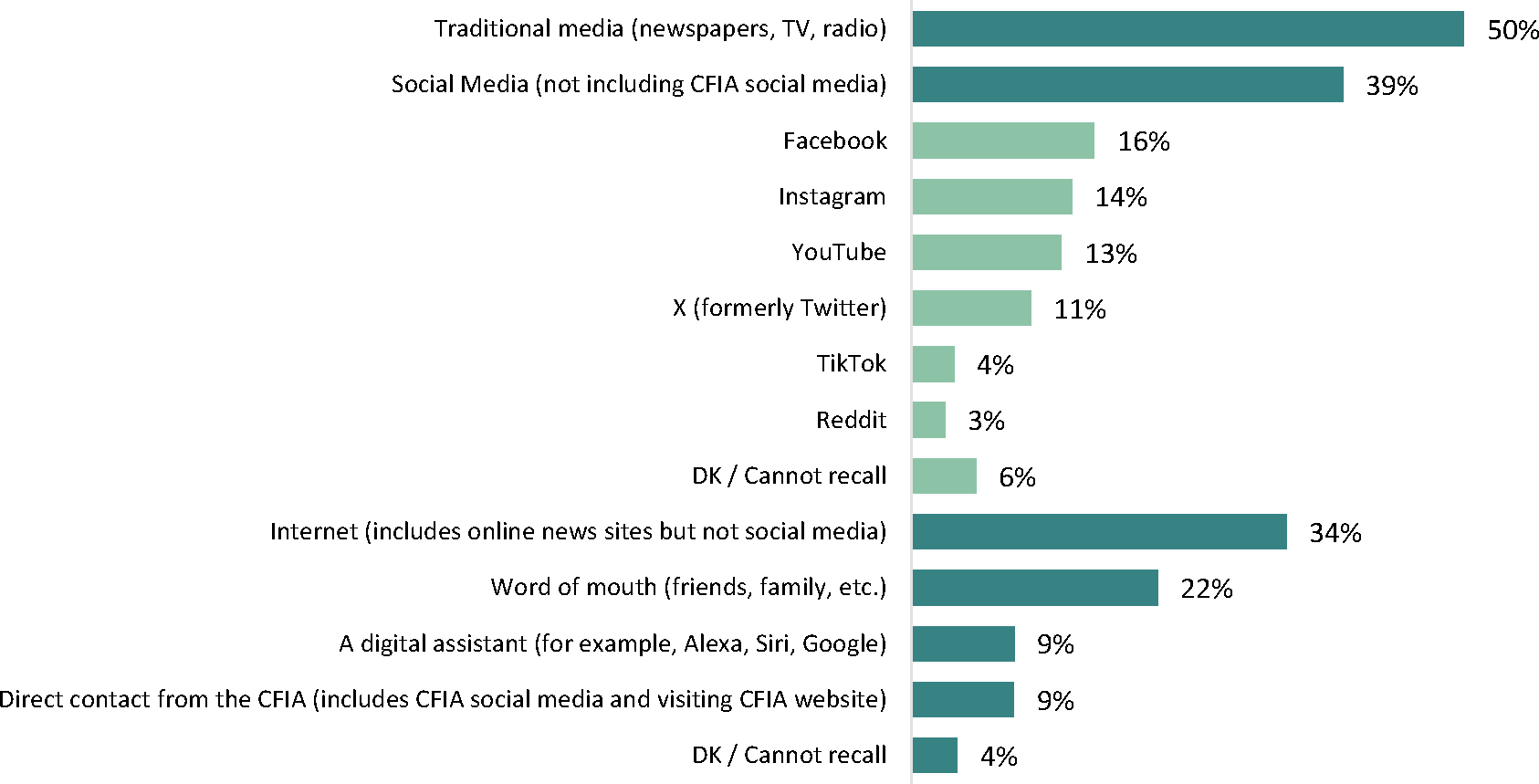

Nearly a quarter of respondents (23%) had recently seen, heard, or read something about the CFIA. When asked where they might have recently seen, heard, or read something about the CFIA, 50% cited traditional media such as newspapers, television, or radio and 39% cited social media (not including the CFIA’s social media) such as Facebook (16%), Instagram (14%), YouTube (13%), X (formerly Twitter, 11%), TikTok (4%), or Reddit (3%). Additionally, more than two thirds of respondents (34%) had recently seen, heard, or read about the CFIA on internet sources other than social media.

Understanding the CFIA

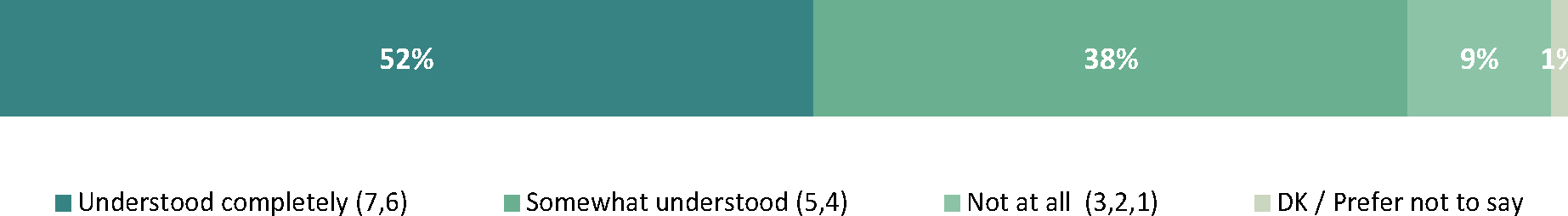

Those who had recently seen, heard, or read something from the CFIA were asked how well they understood the information. More than half of respondents (52%) understood completely (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) and 38% somewhat understood (a score of 4 or 5).

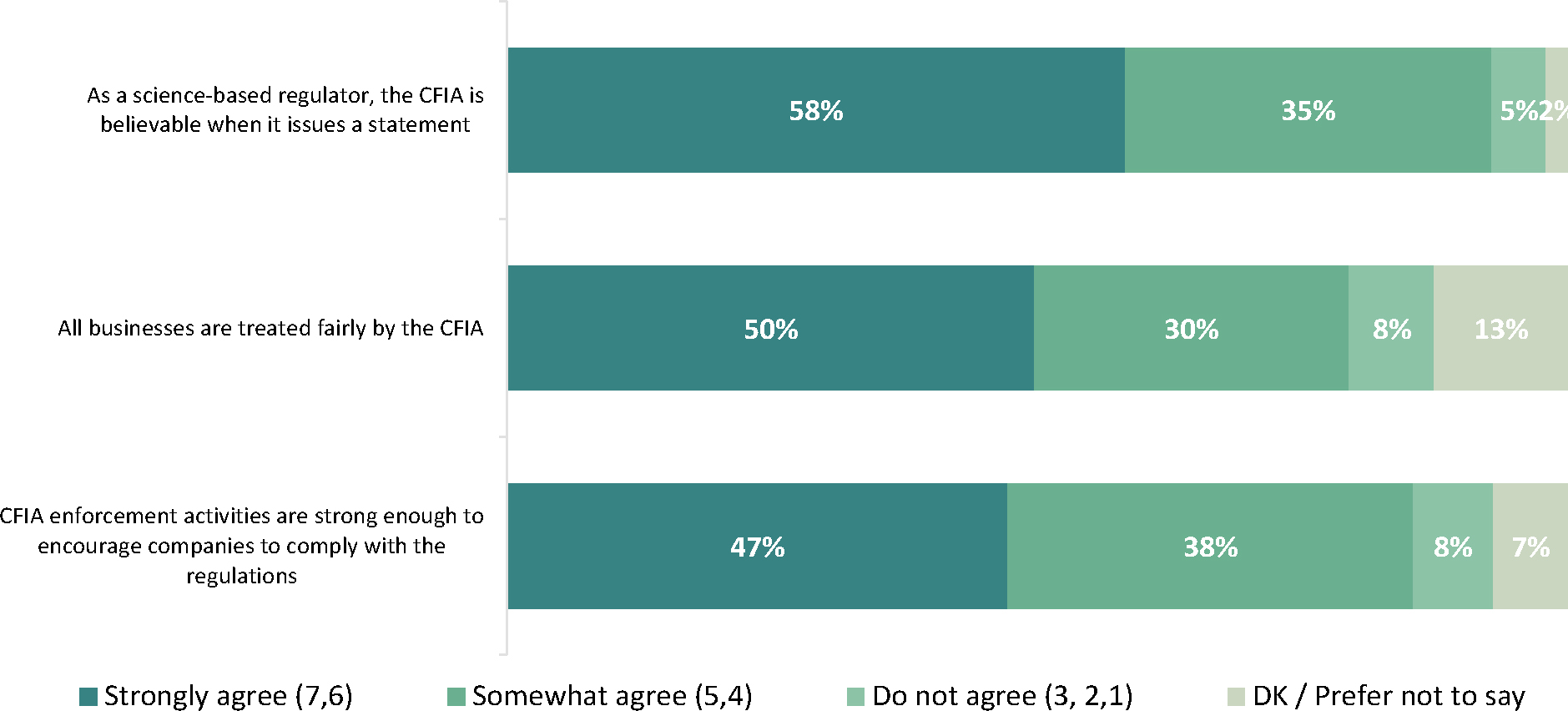

Respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed with various statements regarding the CFIA. Nearly 3 in 5 respondents (58%) strongly agreed that the CFIA is believable when it issues a statement (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale), 50% strongly agreed that all businesses are treated fairly by the CFIA, and 47% strongly agreed that CFIA enforcement activities are strong enough to encourage companies to comply with the regulations.

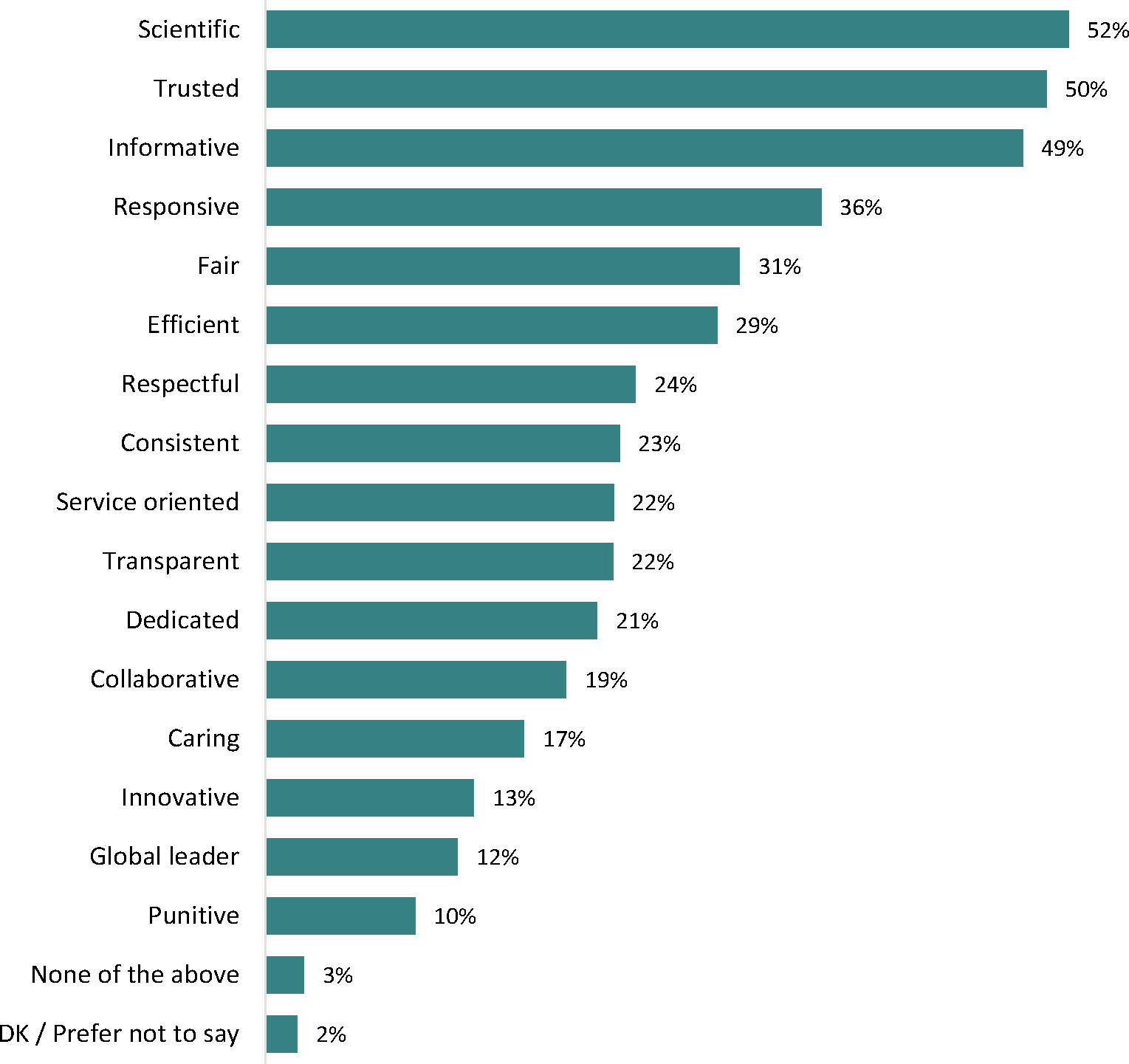

When presented with a list of adjectives and asked which ones best described the CFIA, the most popular terms selected included: scientific (52%), trusted (50%), informative (49%), responsive (36%), fair (31%) and efficient (29%).

CFIA’s role in food safety awareness

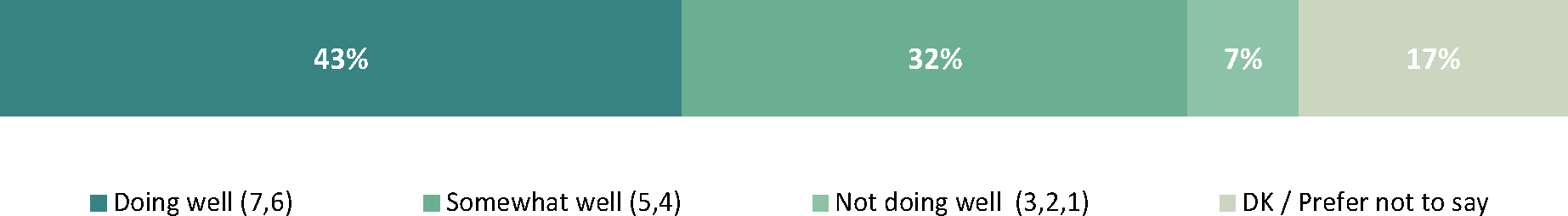

When asked how well they believed the CFIA was doing at safeguarding the food sold in Canada, 43% believed that the CFIA was doing well (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) and 32% believed it was doing somewhat well (a score of 4 or 5).

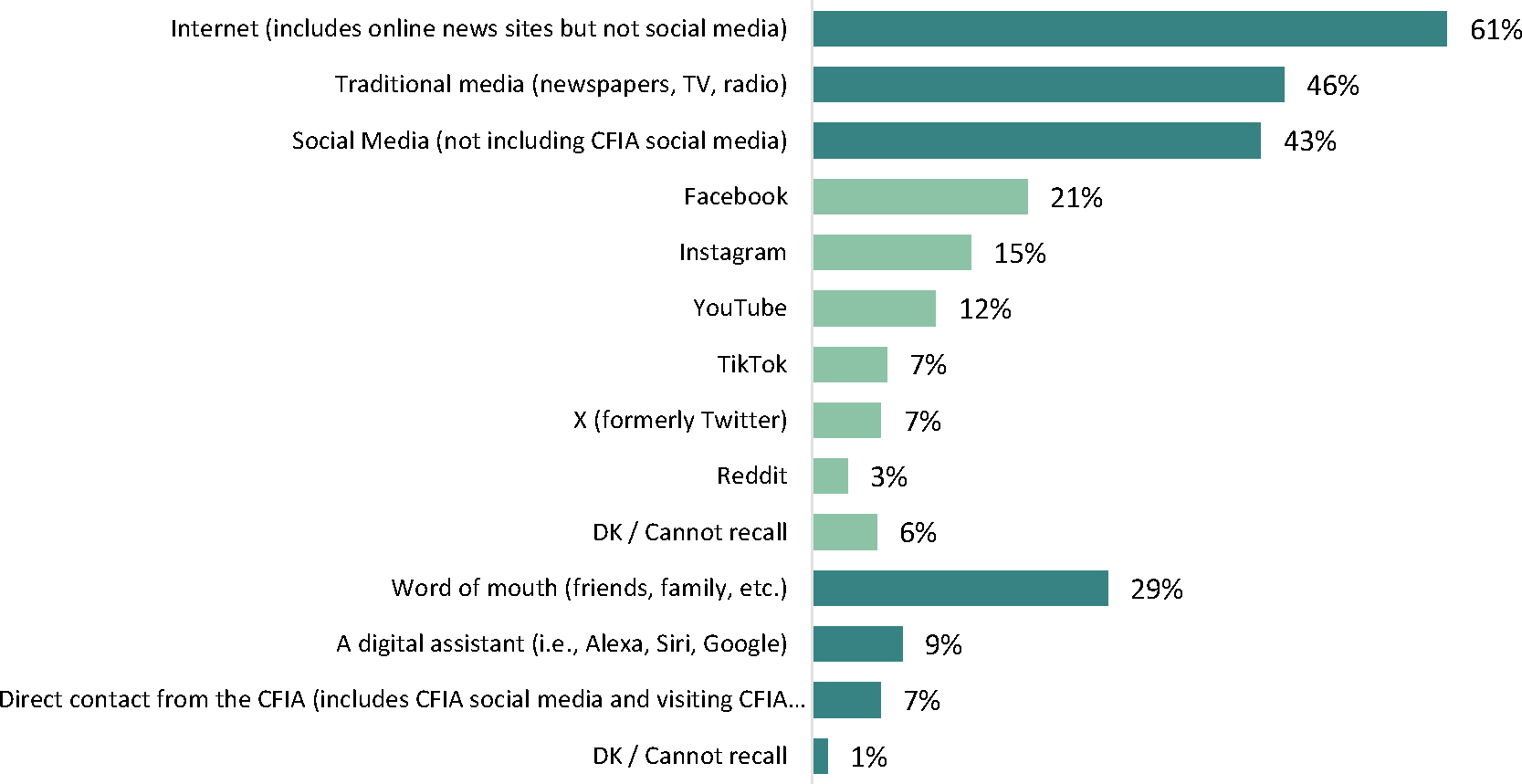

A quarter of respondents (25%) reported that they had looked for or read information specifically about food safety or food fraud over the past few years. Among these respondents, the internet (excluding social media) was the most common source of information (61%) followed by traditional media (46%) and social media (43%).

A majority of respondents (78%) felt the statement “I believe food recalls illustrate that the food safety system is working”, was true.

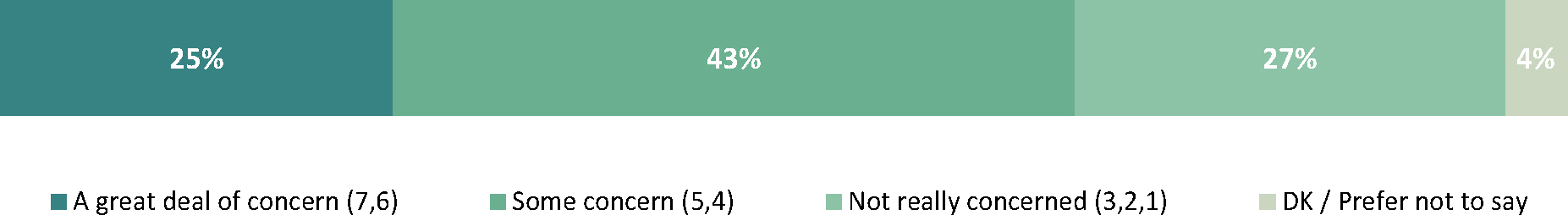

When it comes to food recalls, 25% of respondents would say they had a great deal of concern (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) while 43% had some concern.

Trusting the CFIA’s food safety procedures

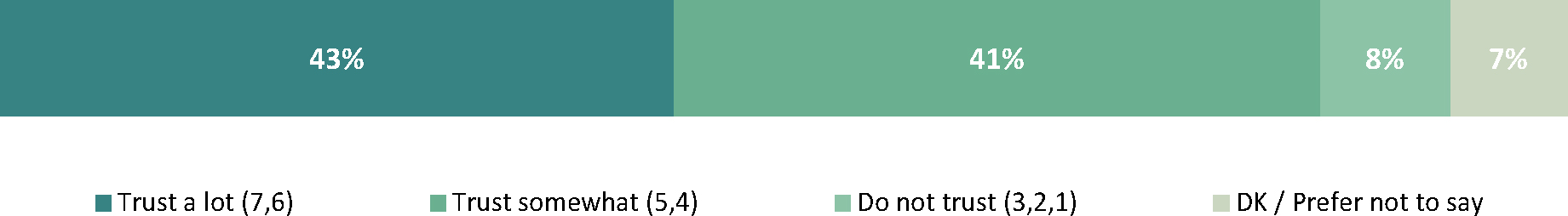

When asked how much they trust the CFIA to do what is right to help ensure that food is safe in Canada, 43% reported high trust (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) and another 2 in 5 (41%) said they somewhat trusted the CFIA to do what is right (a score of 4 or 5).

Respondents were also asked a series of questions related to food consumption and “best-before” dates.

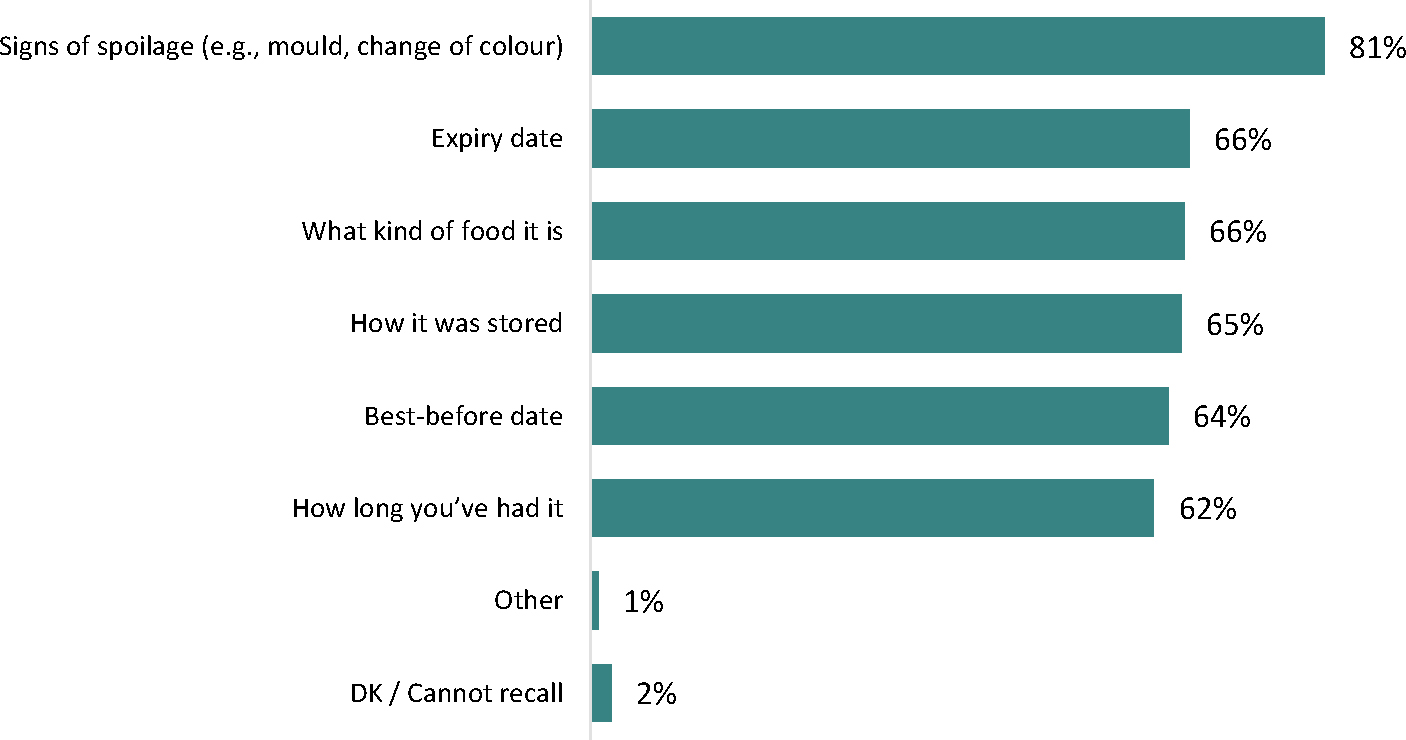

When it comes to deciding whether a food can still be eaten, respondents most commonly look for and consider signs of spoilage (81%), expiry dates (66%), what kind of food it is (66%), how it was stored (65%), “best before” dates (64%) and how long they have had the food (62%).

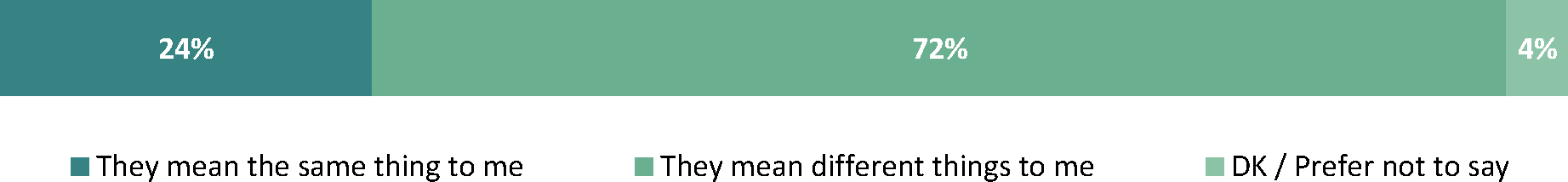

When it comes to “best before” dates and expiration dates, 24% reported that these terms meant the same thing to them while 72% felt the terms meant different things to them.

Other key findings related to date labels, including “best before” dates included:

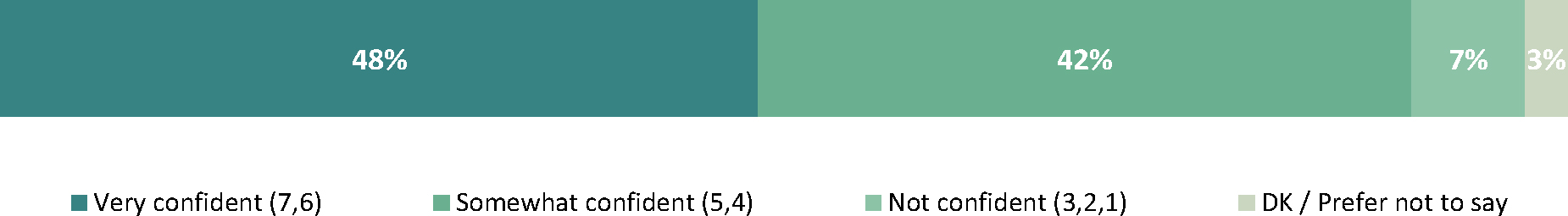

Nearly half (48%) were very confident that they know how to use date labels when judging if a food can still be eaten (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale)

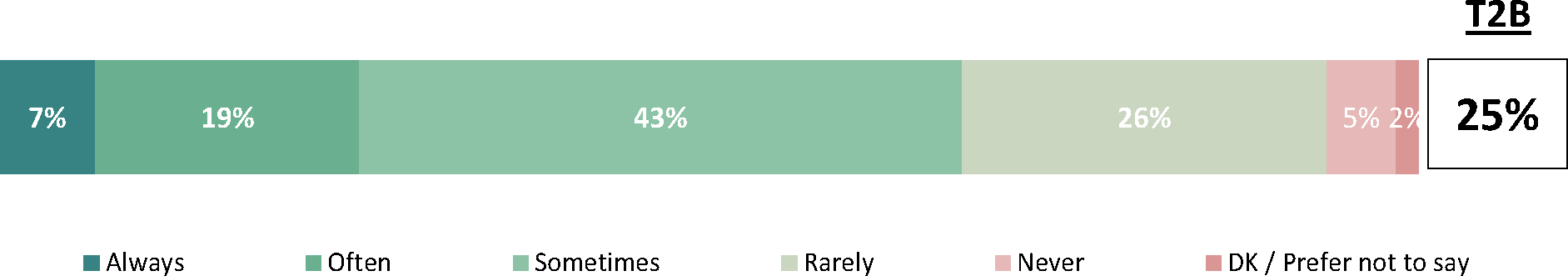

A quarter of respondents (25%) regularly throw out food when it has passed the “best before” date (7% always do while 19% often do) while 43% sometimes do this.

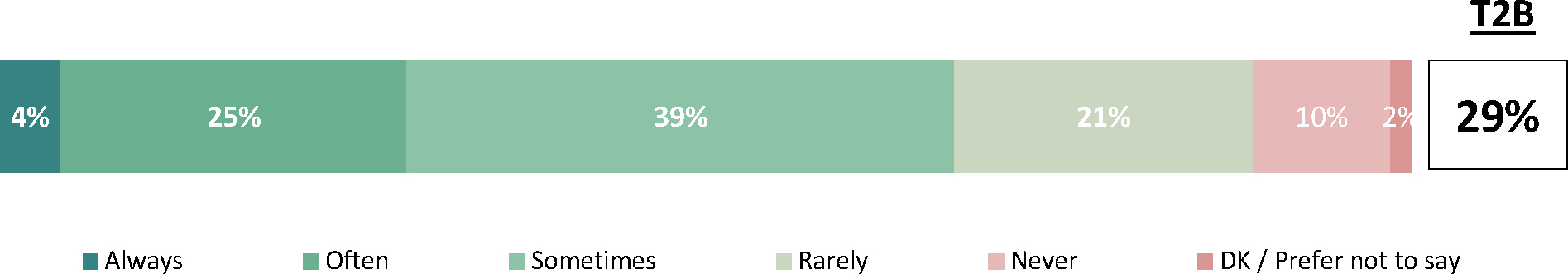

Nearly 3 in 10 respondents (29%) reported that they regularly purchase food that has been discounted because the “best before” date is approaching (4% always do while 25% often do) while 39% sometimes do so.

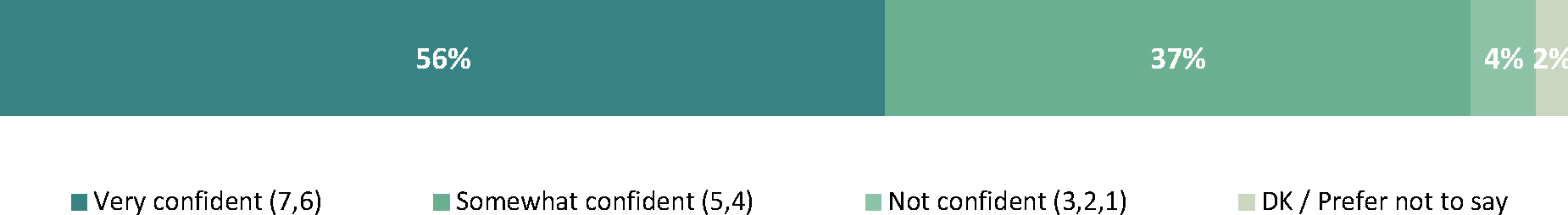

More than half of respondents (56%) reported being very confident in the safety of food sold in Canada (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale). Another 37% said they were somewhat confident (a score of 4 or 5).

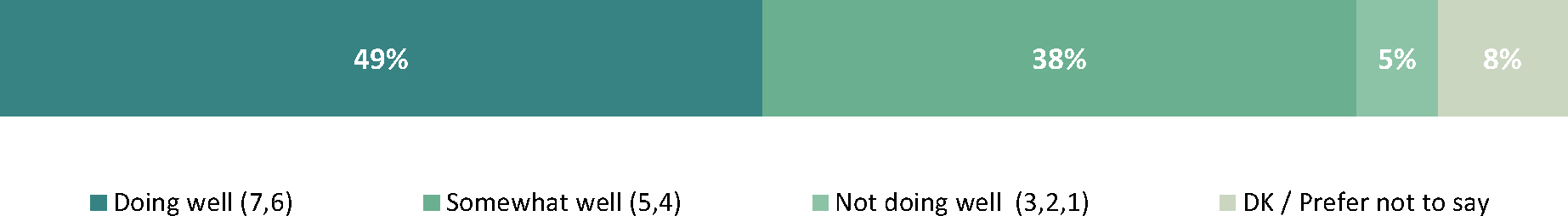

When asked to rate how well they believe the CFIA is doing when it comes to verifying that food sold in Canada is safe, 49% felt that the CFIA was doing well (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point) and 38% felt that the CFIA was doing somewhat well (a score of 4 or 5).

Other key findings related to some of the roles the CFIA plays when it comes to food safety included:

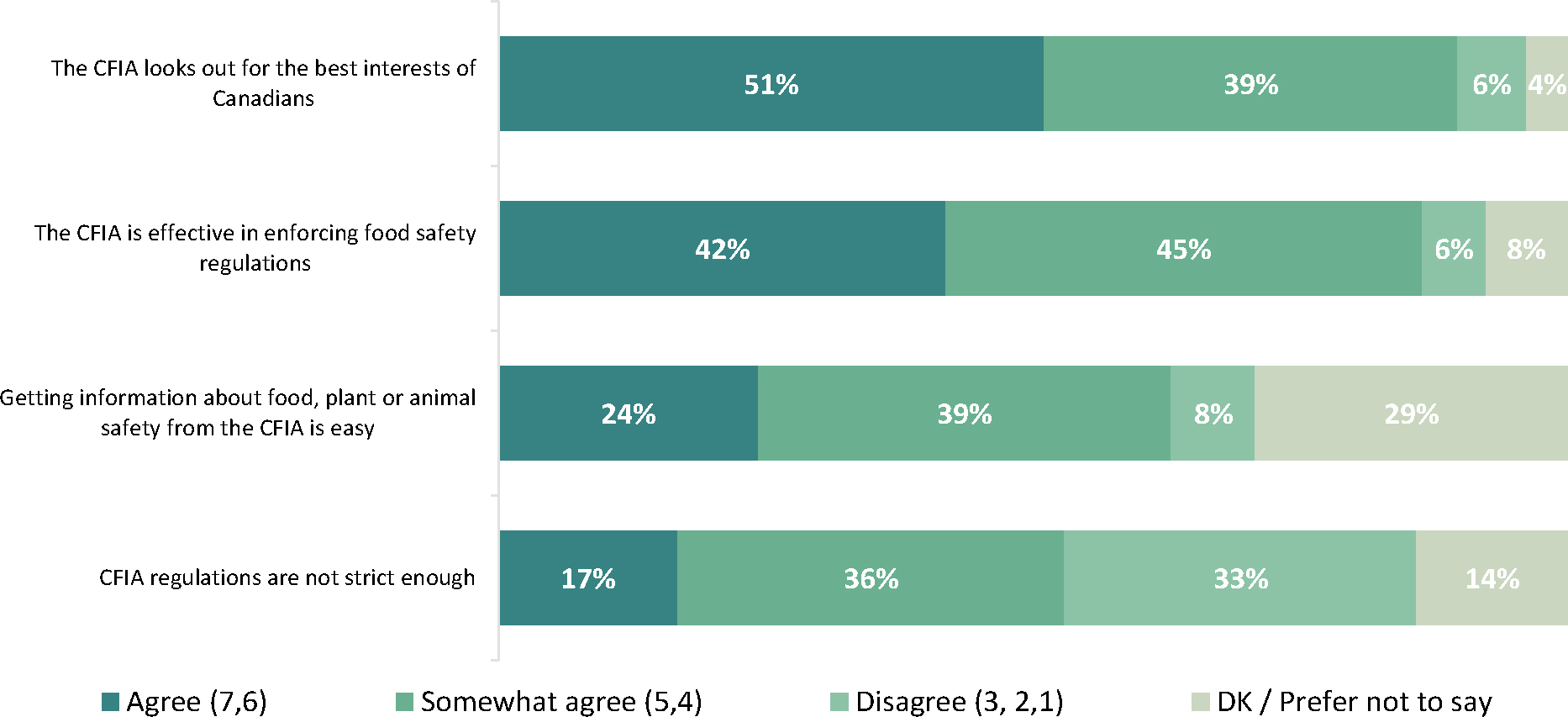

Just over half of respondents (51%) agreed (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) that the CFIA looks out for the best interests of Canadians,

More than 2 in 5 (42%) agreed that the CFIA is effective in enforcing food safety regulations.

Roughly a quarter (24%) agreed that getting information about food, plant or animal safety from the CFIA is easy while 39% somewhat agreed.

Less than a fifth (17%) agreed that CFIA regulations are not strict enough while 36% somewhat agreed.

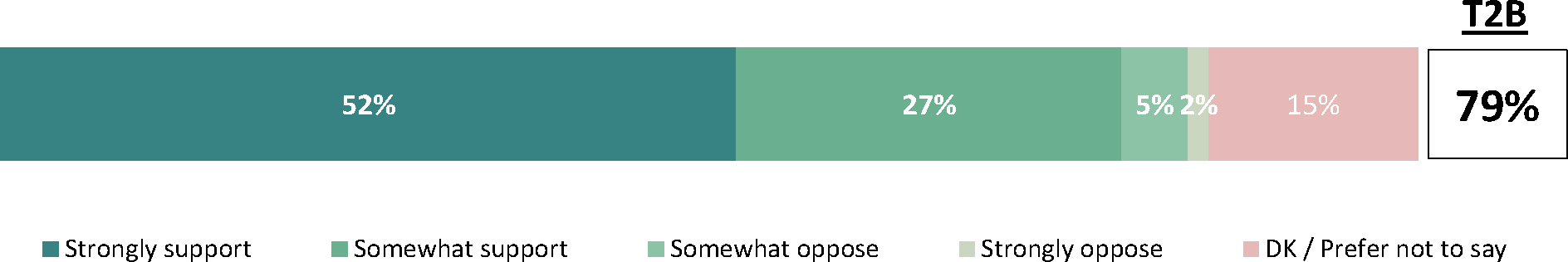

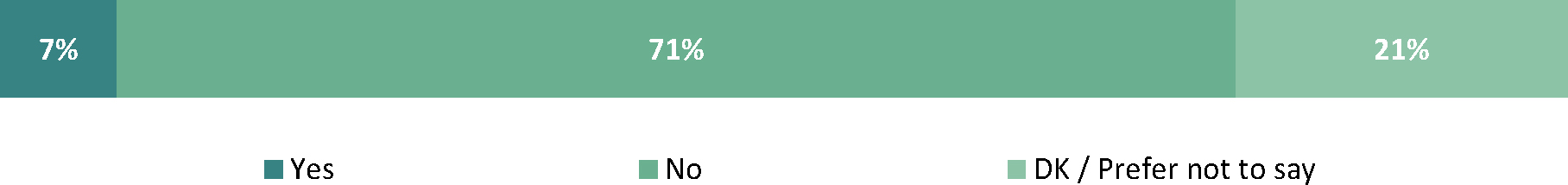

Overall, 79% support the CFIA publishing names of companies that receive administrative monetary penalties (AMP’s) due to having not complied with regulations.

Food fraud

Next, respondents were asked a series of questions related to food fraud.

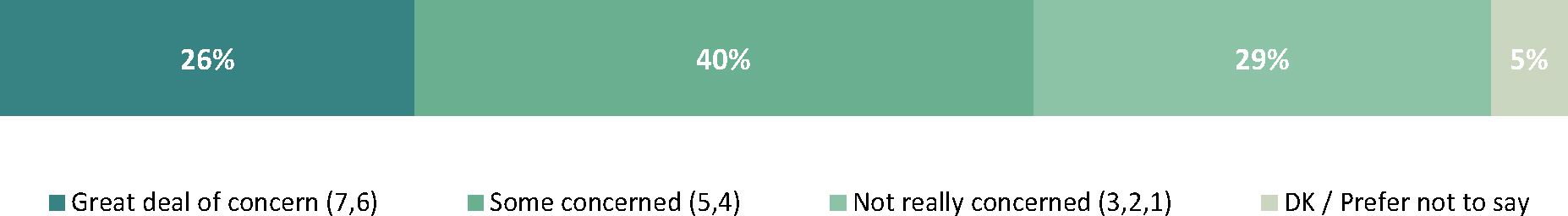

Just over a quarter of respondents (26%) reported a great deal of concern regarding food fraud when they go grocery shopping while 40% were somewhat concerned.

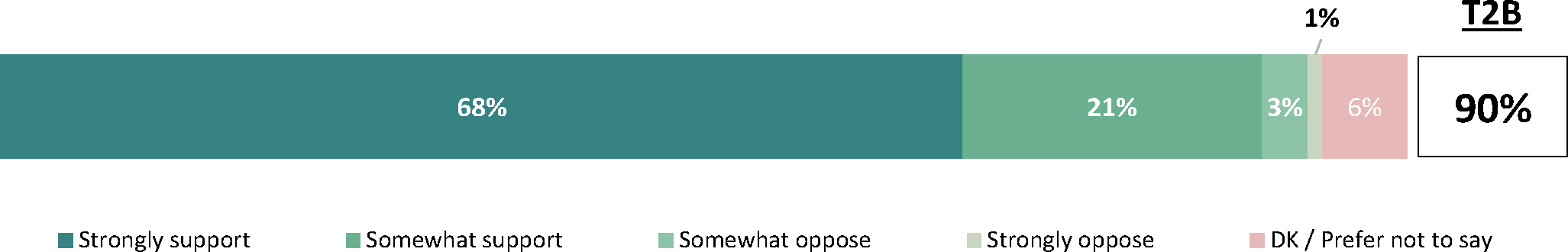

For the most part, respondents support the CFIA publishing names of companies that have been found to have committed food fraud (68% strongly support while 21% somewhat support).

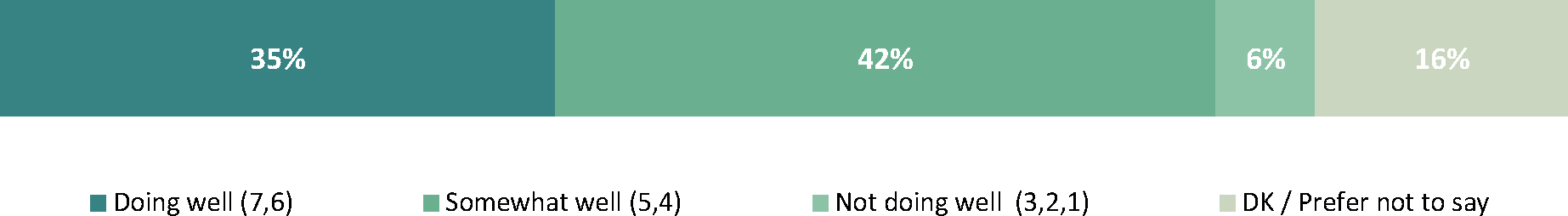

When asked how well they believed the CFIA was doing when it comes to safeguarding from misrepresented food sold in Canada, 35% believed that the CFIA was doing well (a score of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale). Additionally, 42% believed the CFIA was doing somewhat well (a score of 4 or 5).

Other key findings related to the role the CFIA plays in relation to food fraud included:

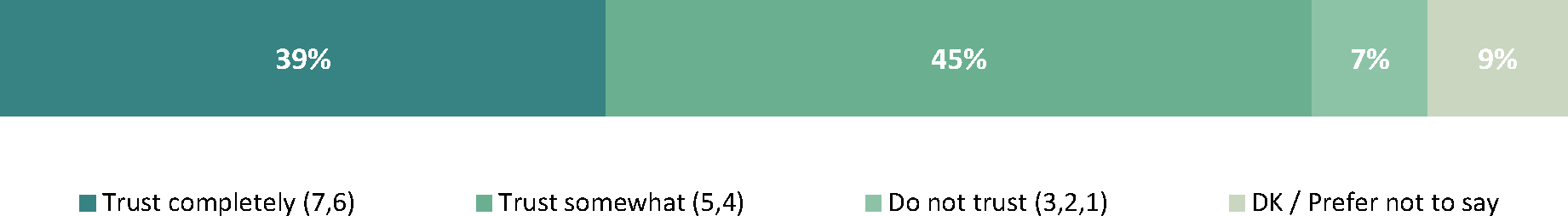

Nearly 2 in 5 respondents (39%) reported a high level of trust in the CFIA to inspect food product labels for ingredients to which people may be allergic or sensitive (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale).

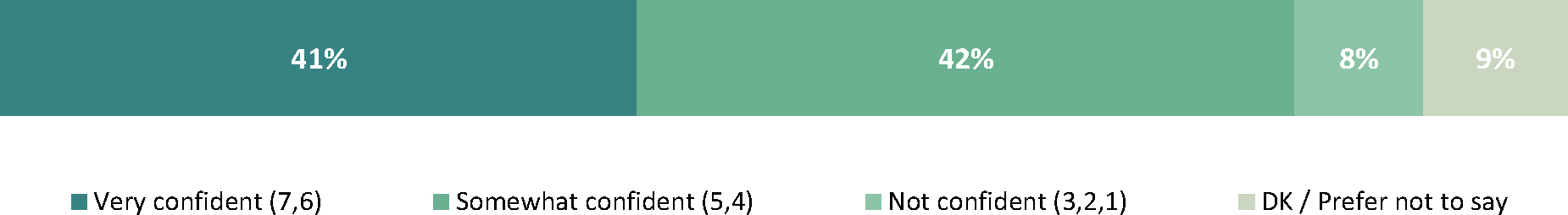

A similar proportion (41%) reported high confidence that the CFIA will take enforcement action to protect consumers from food fraud (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale).

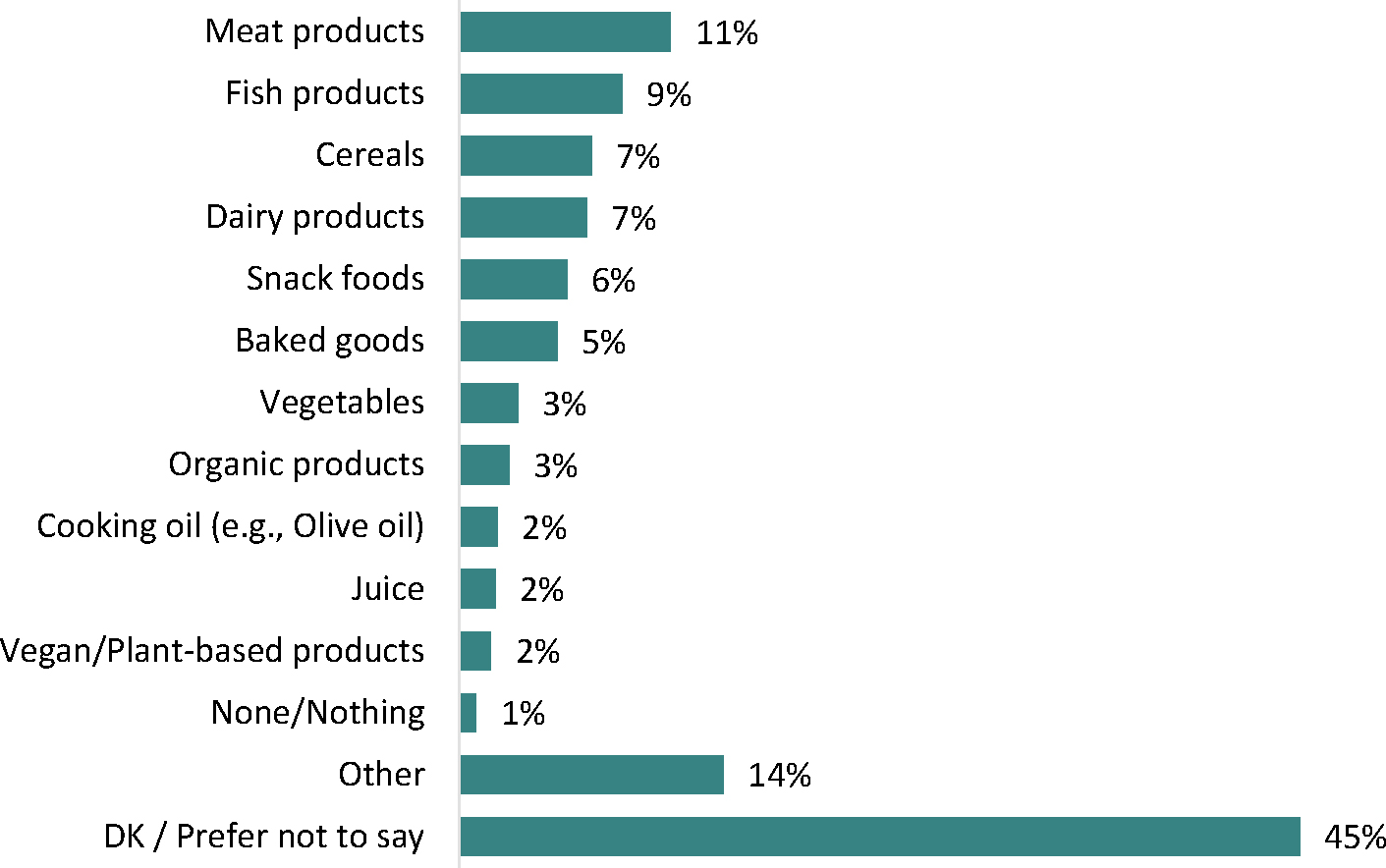

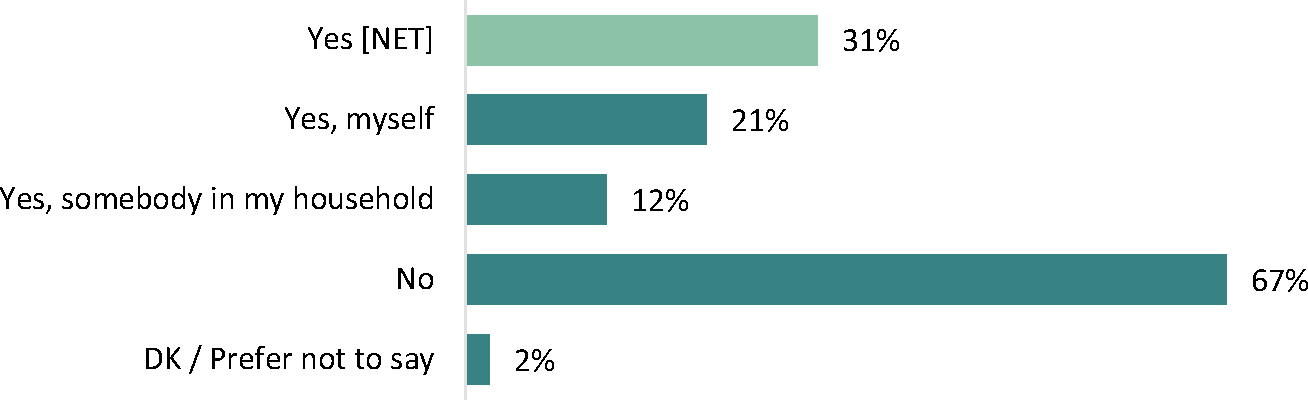

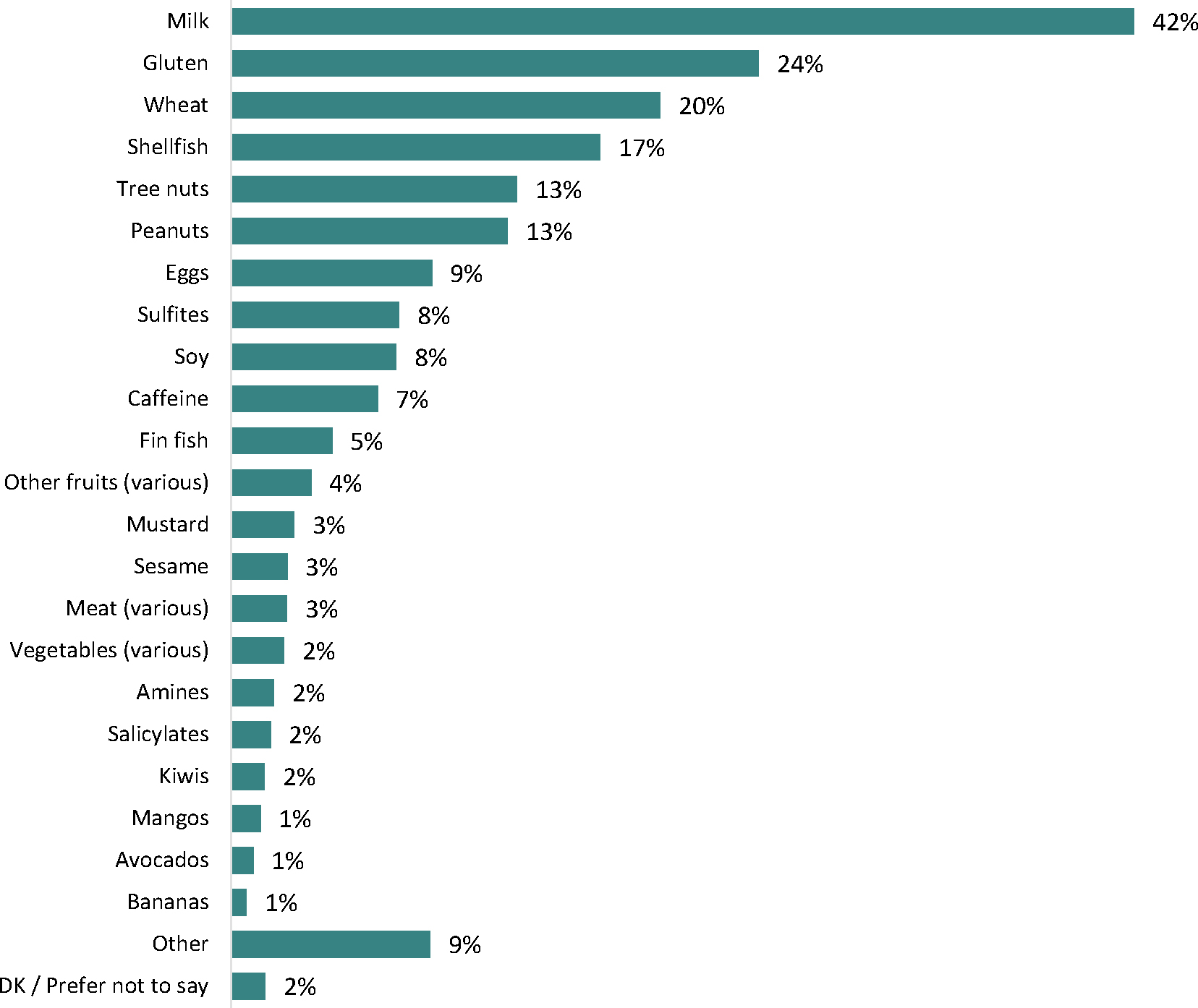

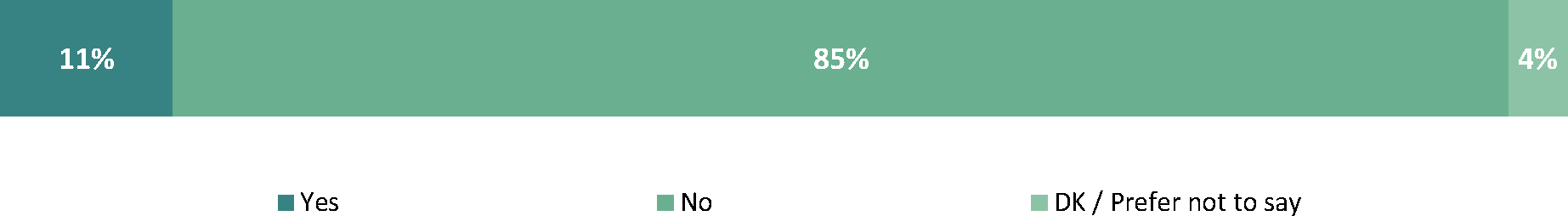

Less than 1 in 10 (7%) had experienced food fraud within the past year. Among these respondents (n=111), 11% believed they had encountered misrepresented meat products, followed by fish products (9%), cereal (7%), dairy products (7%), snack foods (6%), baked goods (5%), vegetables (3%), organic products (3%), cooking oils (2%), juice (2%) and vegan products (2%).

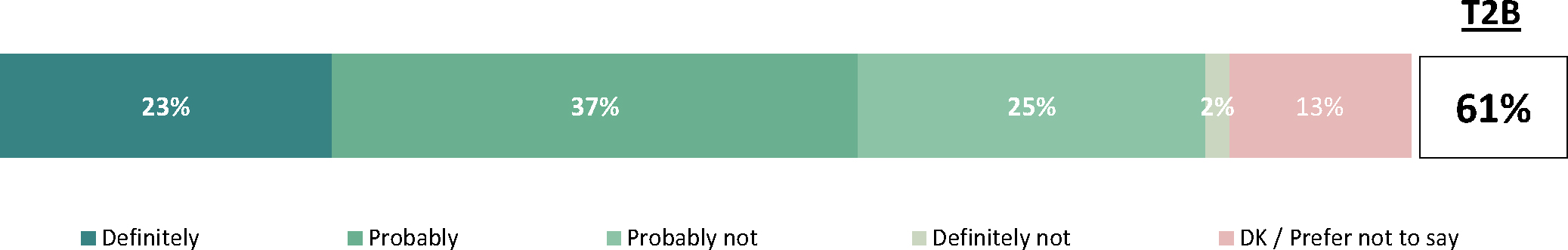

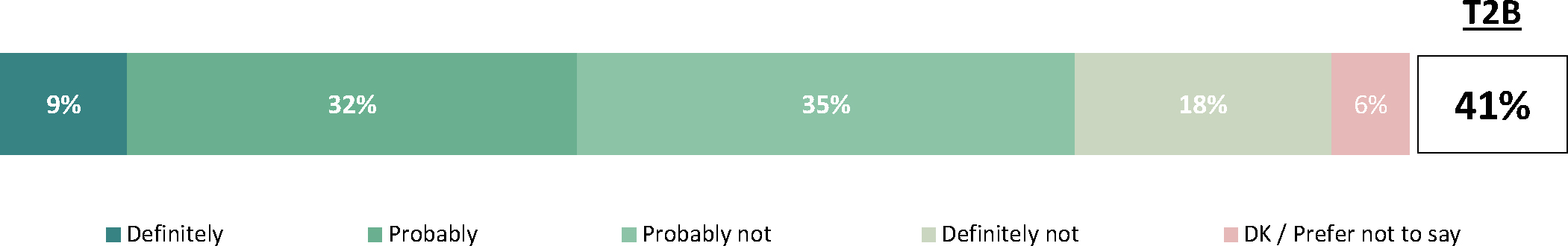

Nearly a quarter of respondents (23%) said that if they suspected food fraud, they would definitely report it to the CFIA, while more than one third (37%) would probably report it. Among these respondents, 41% would know how to report it (9% definitely, 32% probably).

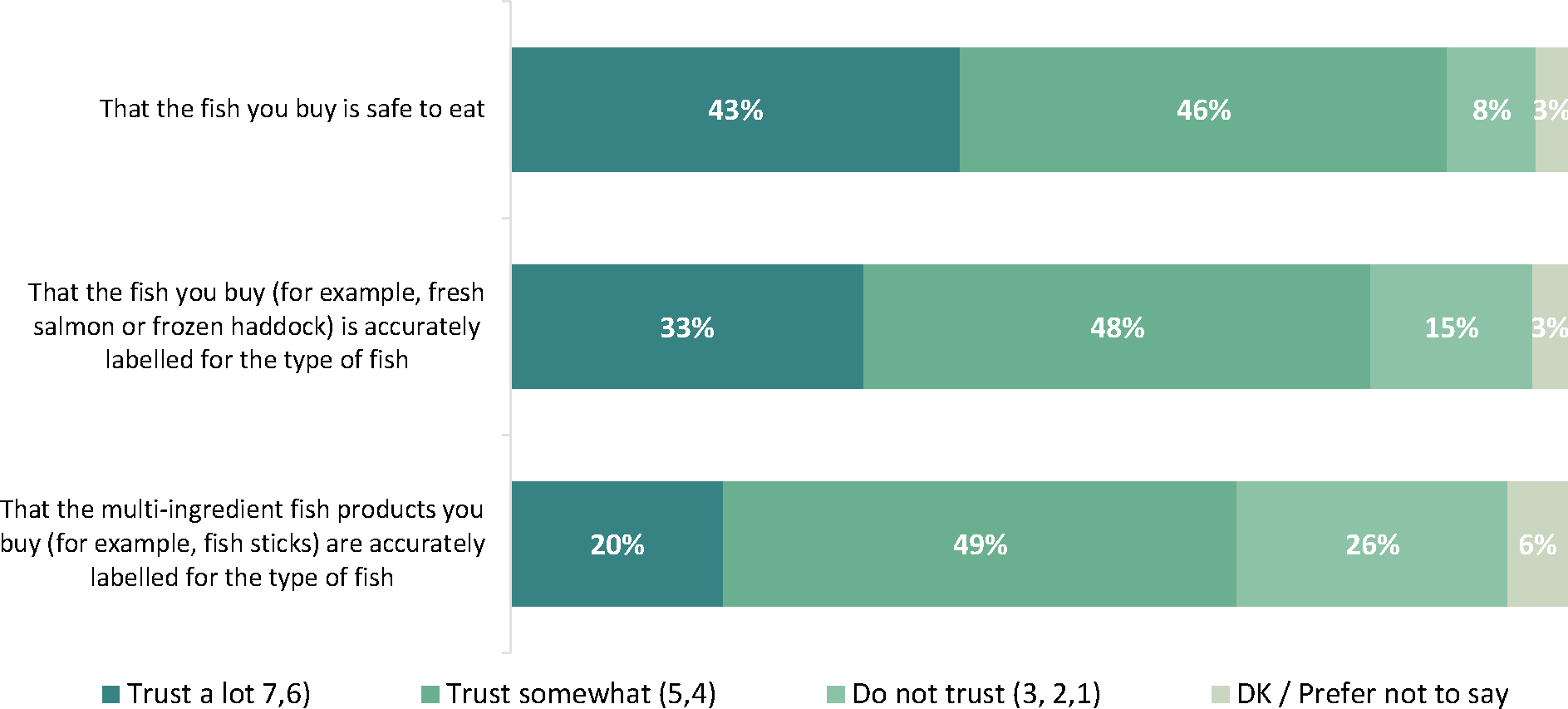

More than 1 in 10 respondents reported not eating or buying fish (13%). Those who eat or buy fish were asked to rate their level of trust on a series of statements related to fish products:

More than 2 in 5 respondents (43%) reported high trust (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) that the fish they buy is safe to eat while 46% reported moderate trust (scores of 4 or 5).

A third (33%) reported high trust that the fresh fish they buy is properly labelled for the type of fish that it is while 48% reported moderate trust.

When it comes to the multi-ingredient fish products that respondents buy (for example, fish sticks), 20% had high trust that these products are accurately labelled for the type of fish they contain while 49% reported moderate trust.

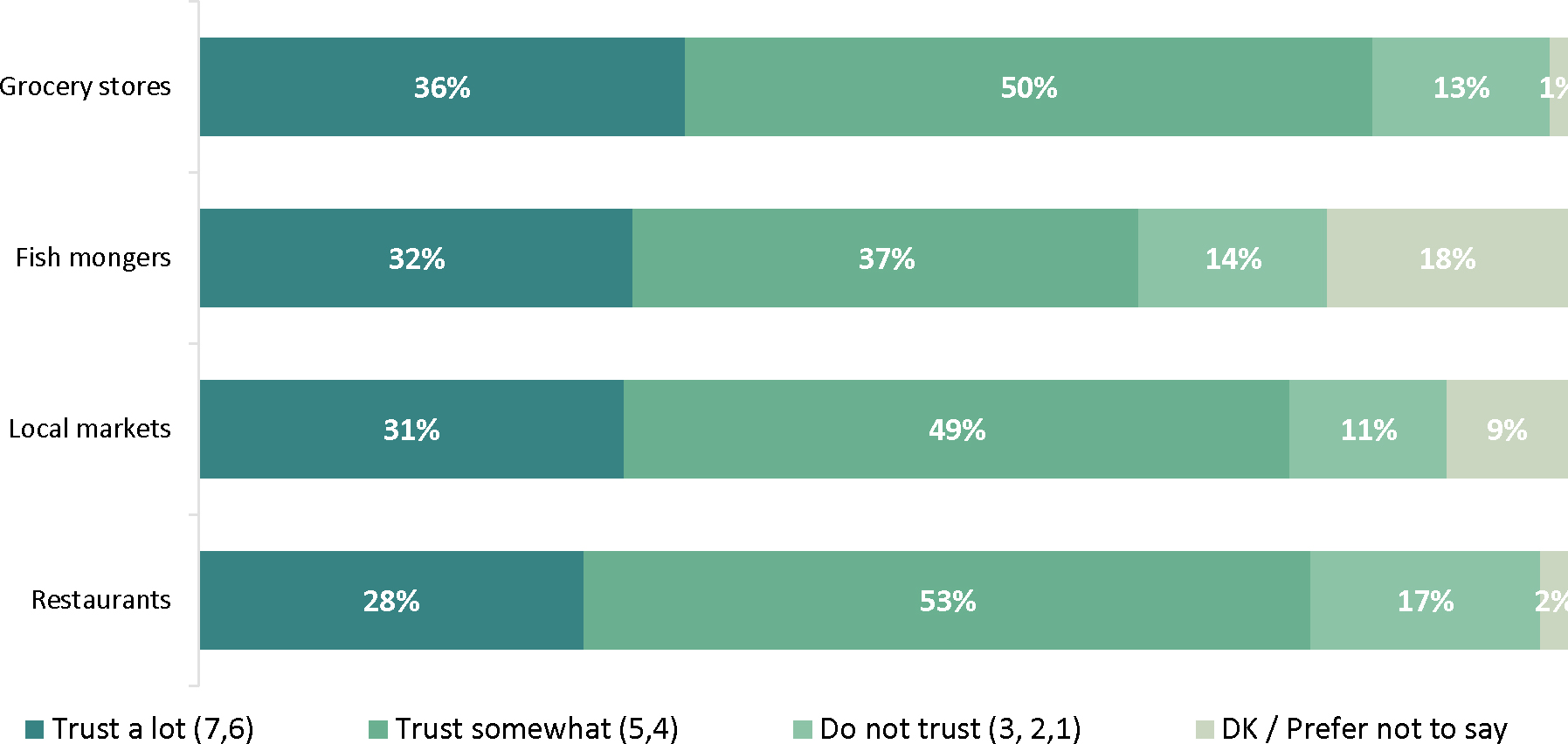

Respondents who eat or buy fish were also asked to which extent they trust various locations when it comes to the fish that they sell. Trust was highest when it comes to grocery stores with 36% reporting high levels of trust (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale). This was followed by fish mongers (32%), local markets (31%) and restaurants (28%).

Quantitative research results – telephone survey with Canadian food businesses

Awareness of food safety regulations

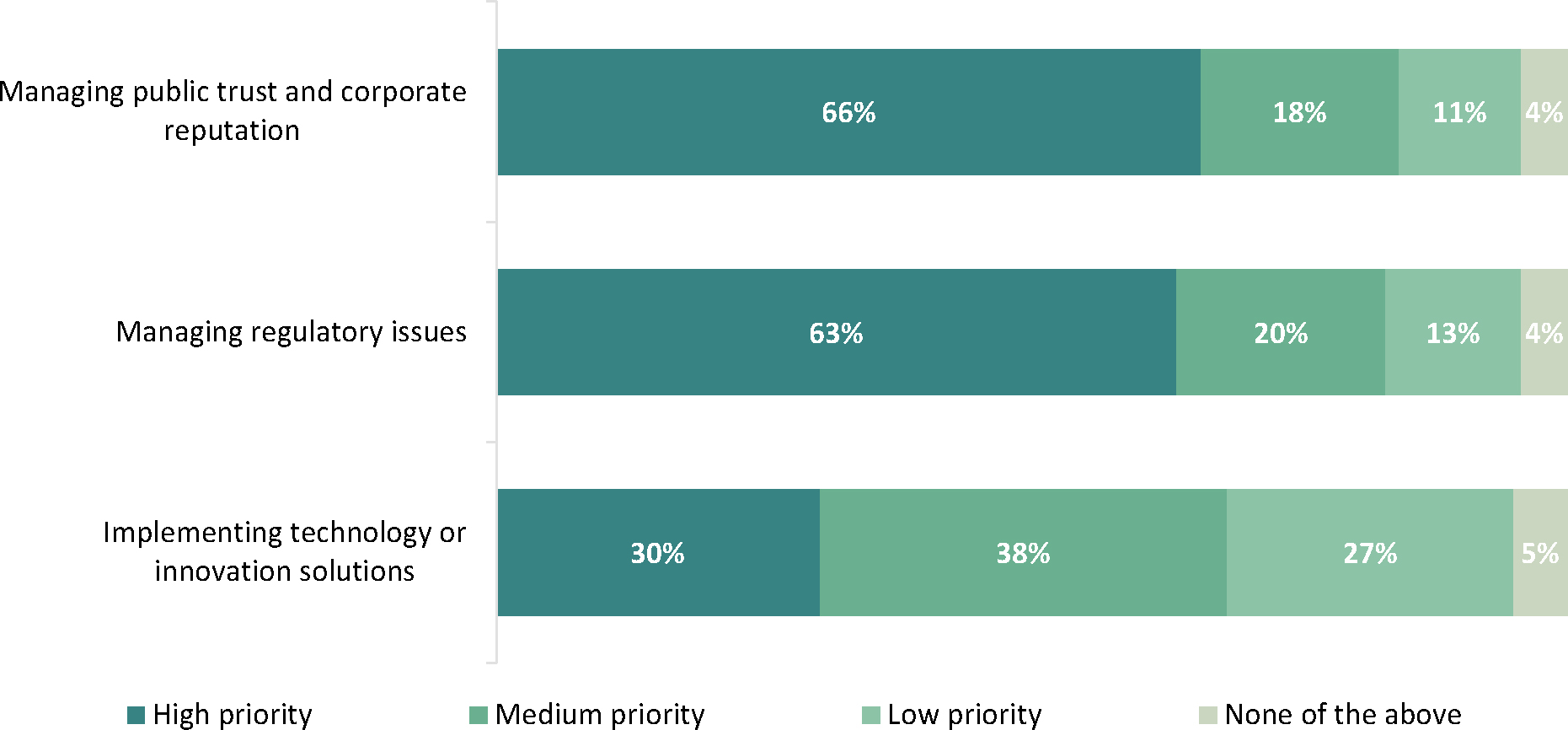

Two thirds of business representatives (66%) reported managing public trust and corporate reputation as a high priority and a similar proportion (63%) reported managing regulatory issues as a high priority. Fewer said that implementing new technology or innovative solutions was a high priority for their business (30%).

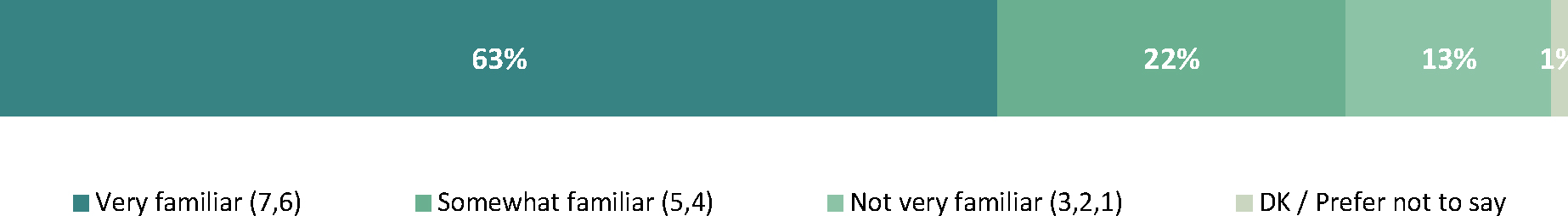

Nearly two thirds of businesses (63%) reported being very familiar (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) with the activities of the CFIA while 22% were somewhat familiar (scores of 4 or 5).

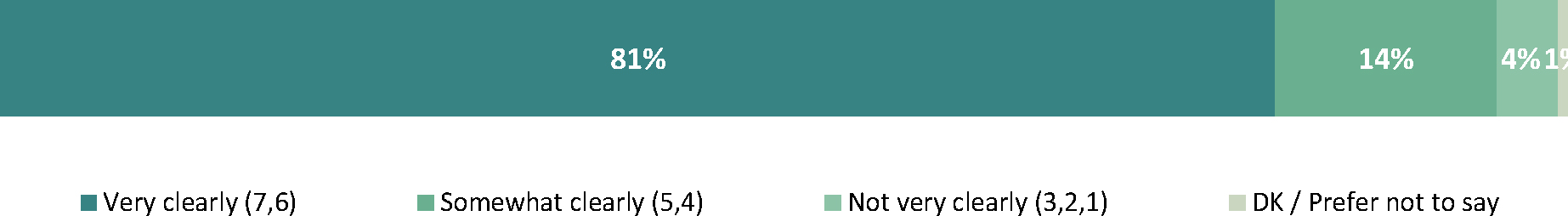

Roughly 4 in 5 (81%) believe they clearly understand the food safety regulations that apply to their business (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) while 14% understand the applicable regulations somewhat well (scores or 4 or 5).

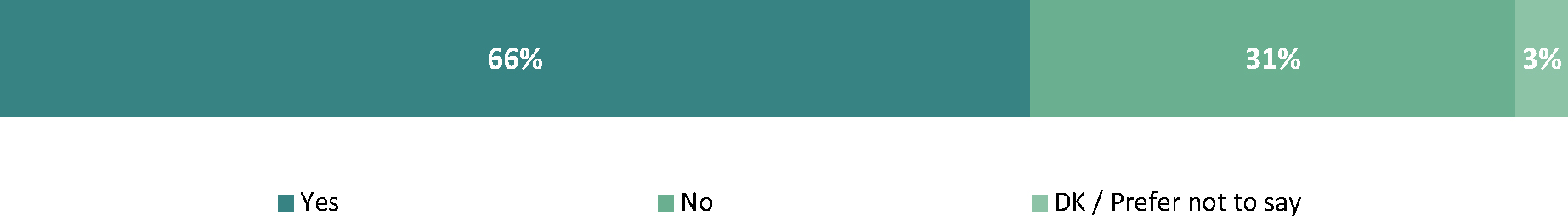

Two thirds of business representatives (66%) had recently seen, heard, or read something about the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SFCR).

Key findings among those familiar with the SFCR included,

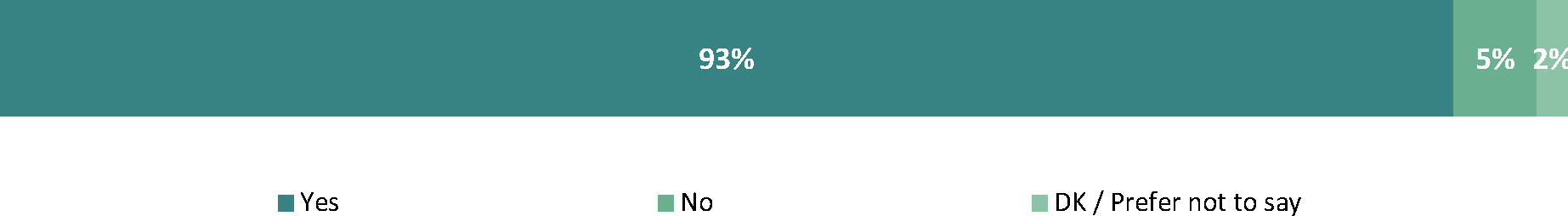

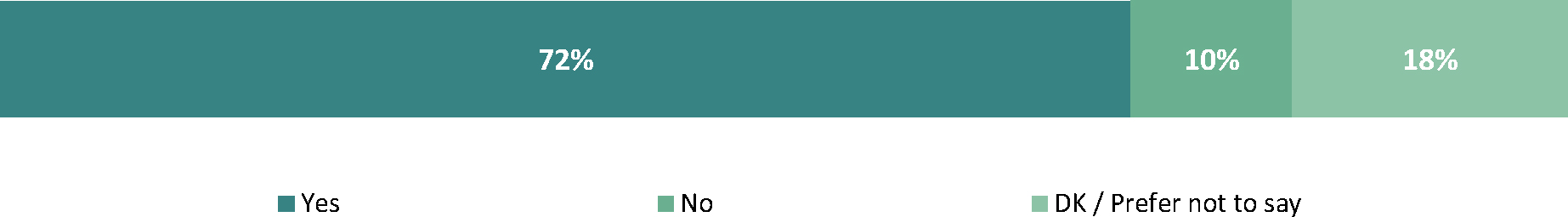

A majority (93%) believed the SFCR applied to their business while 72% believed that the SFCR applied to online sales of food products.

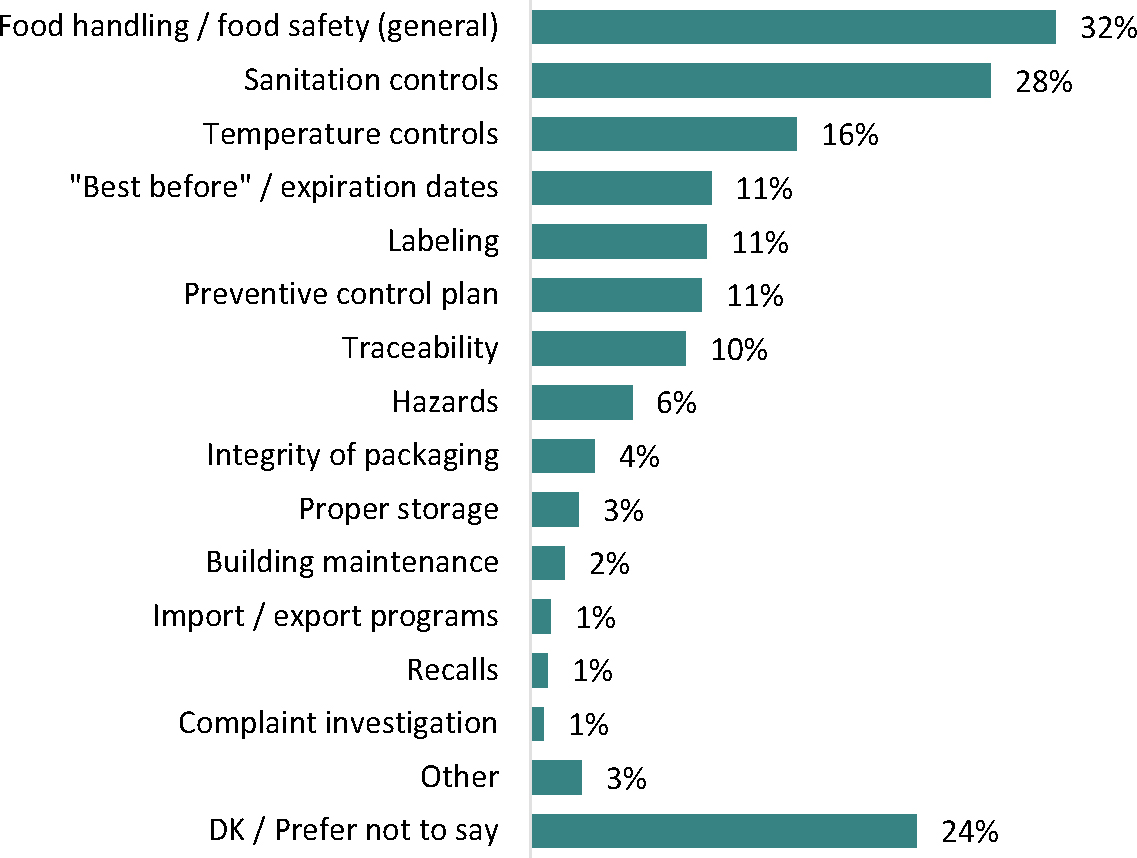

Business representatives believed that the key safety requirements of the SFCR were general food handling or food safety (32%), sanitation controls (28%), temperature controls (16%), “best before” or expiration dates (11%), labeling (11%), preventative control plans (11%) and traceability (10%).

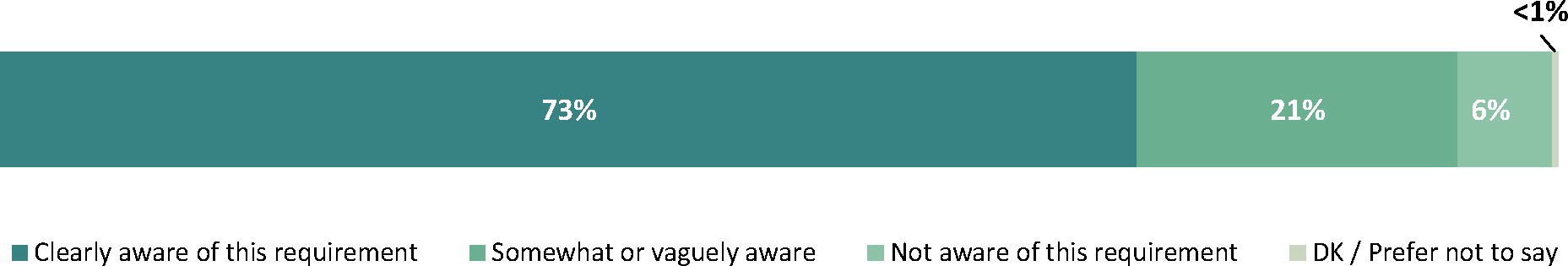

Nearly three quarters (73%) were clearly aware that a licence is required to import food products into Canada while 21% were somewhat aware.

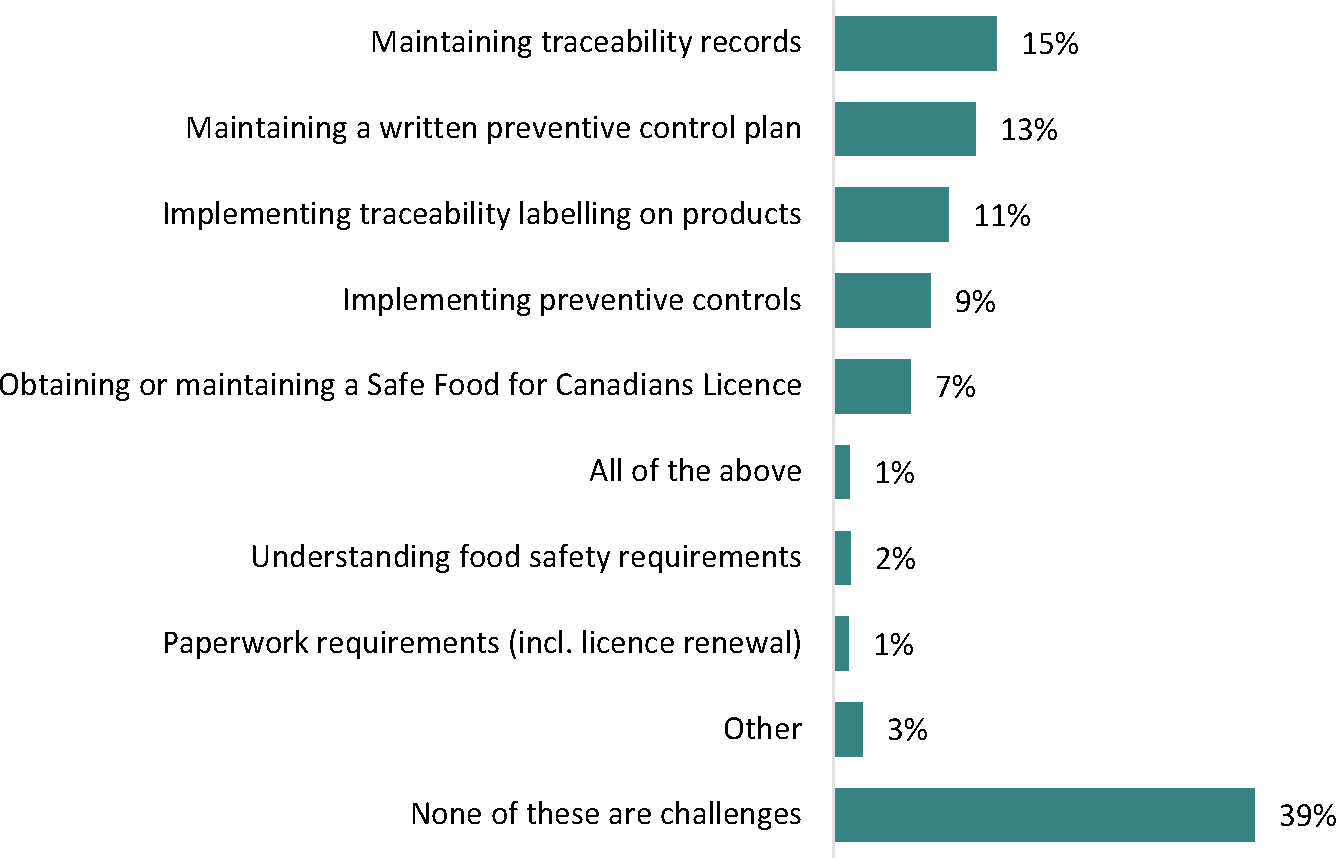

Maintaining traceability records was the biggest challenge of the SFCR (15%) followed by maintaining a written preventative control plan (13%) or implementing traceability labelling on products (11%).

Just under two fifths (39%) felt that none of the requirements were challenges for their business.

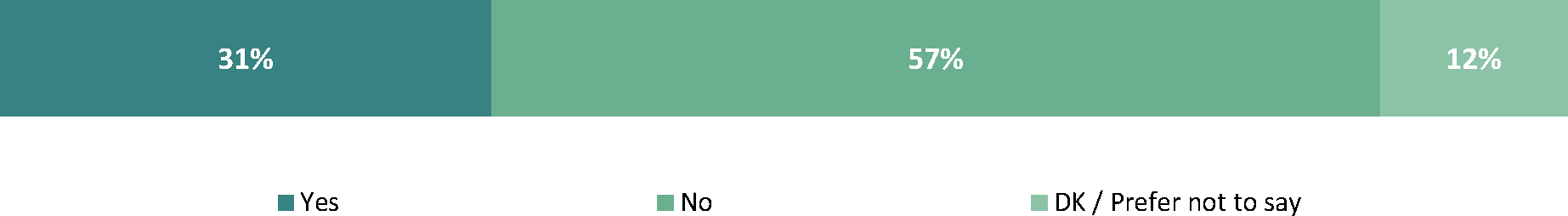

Nearly a third of business representatives (31%) reported that their business uses a private food safety or quality control certification system.

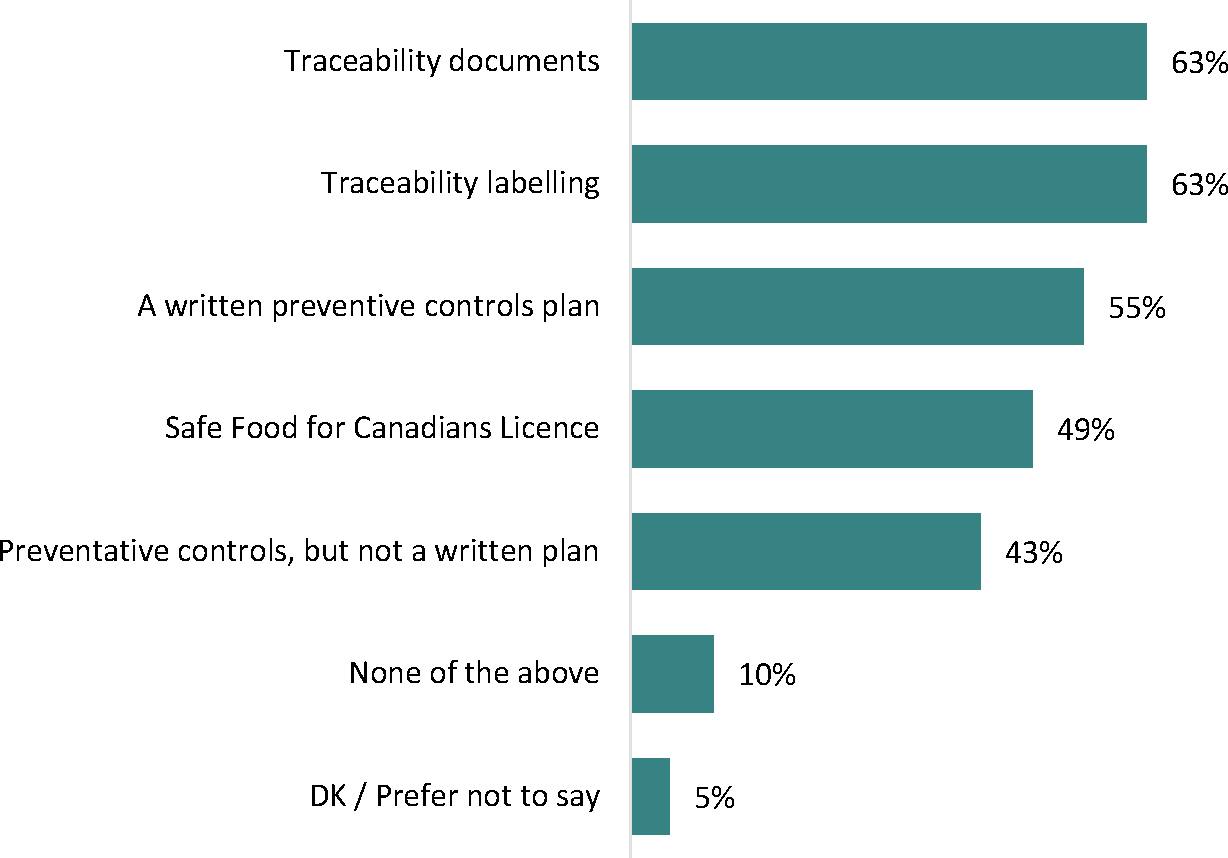

The most commonly used preventative measures used by businesses were traceability documents (63%) or traceability labelling (63%) followed by written preventative controls plans (55%) and having a SFCR licence (49%).

Transparency

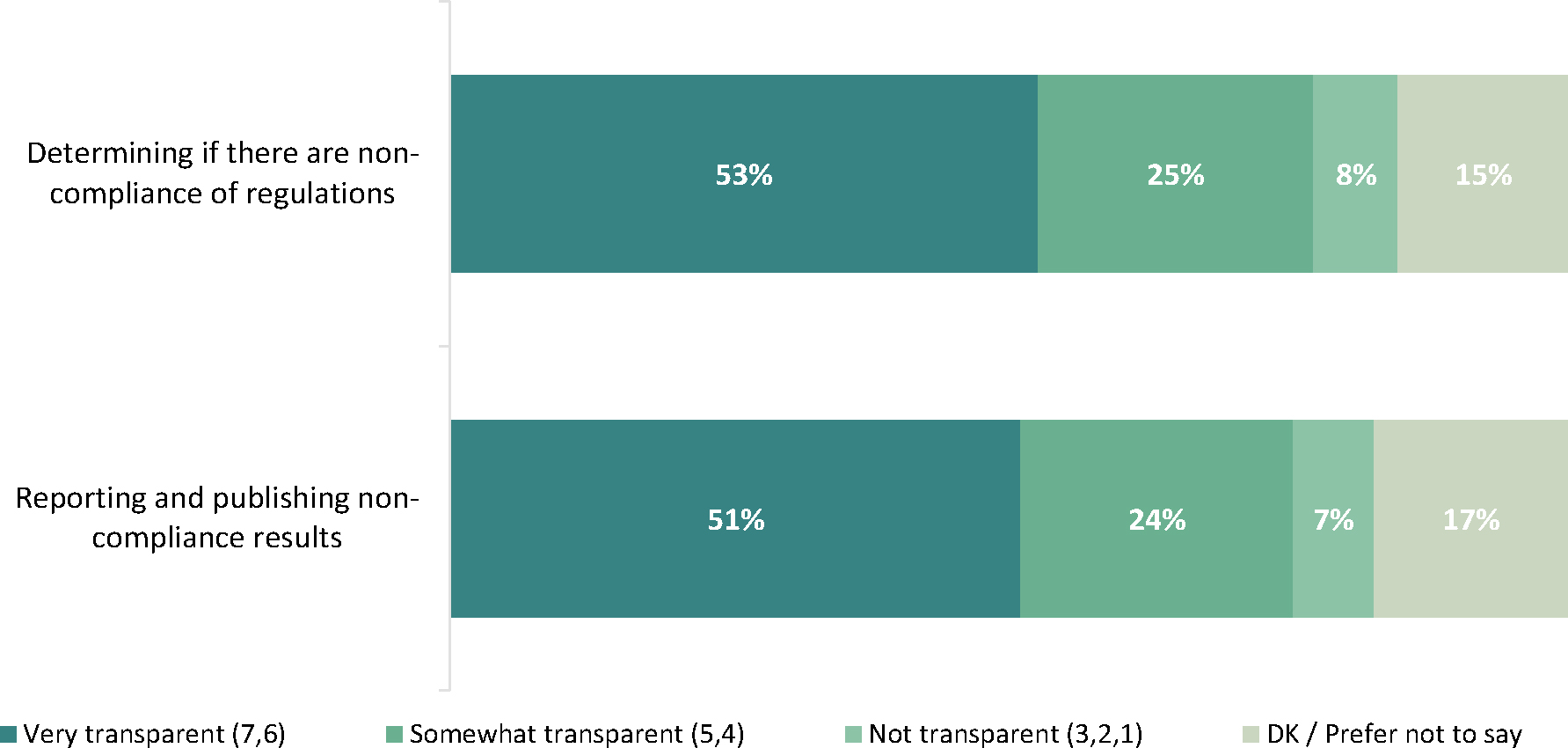

More than half of business representatives (53%) viewed the CFIA as very transparent (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) when it comes to determining if there are non-compliance of regulations while another quarter (25%) felt the CFIA was somewhat transparent (scores of 4 or 5) in this regard, while 8% believed they CFIA was not very transparent (scores of 1, 2 or 3).

Just over half (51%) felt that the CFIA was very transparent when it comes to reporting and publishing non-compliance results while nearly a quarter (24%) believed the CFIA was somewhat transparent in this regard. On the other hand, 7% viewed the CFIA as not very transparent.

“Best before” dates

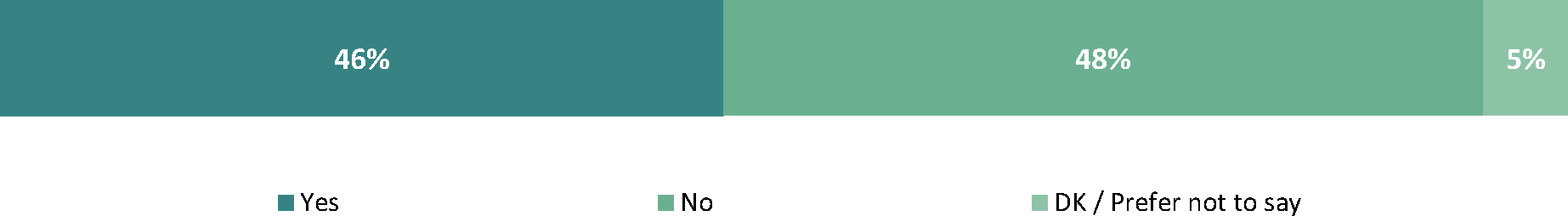

Nearly half (46%) reported that their business benefits from “best before” date requirements.

Nearly two fifths (39%) reported that their business experiences negative impacts from “best before” date requirements.

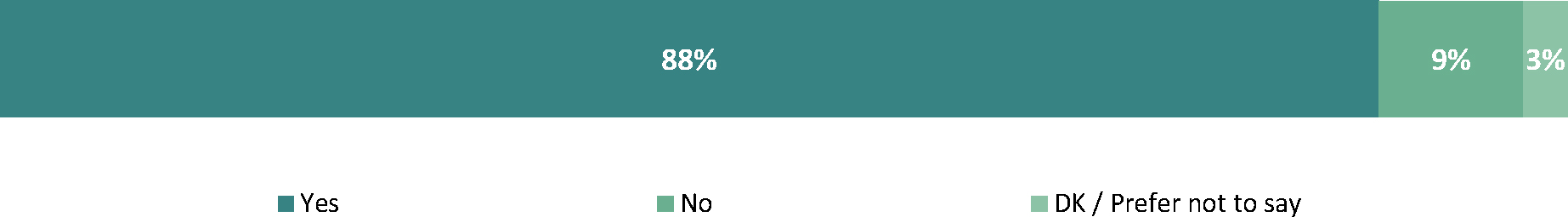

A large majority of business representatives (88%) believed that there is a connection between “best before” dates and food waste.

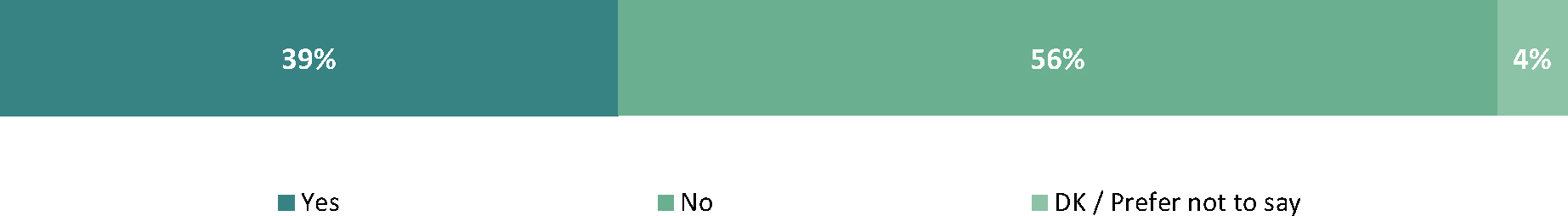

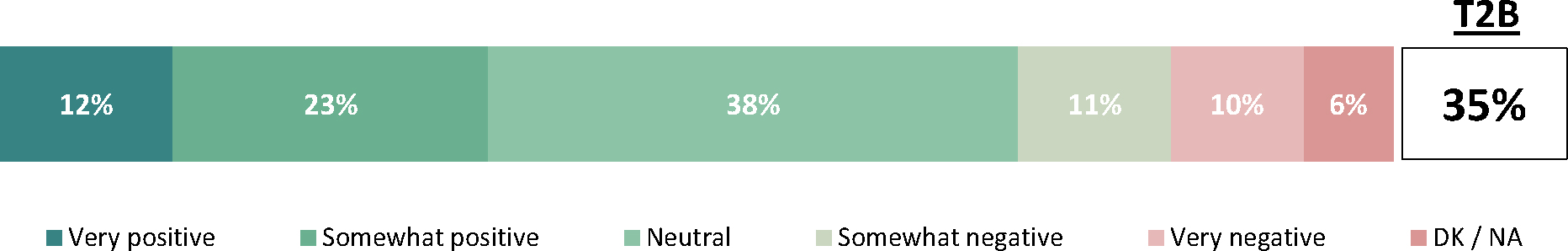

More than one third (35%) perceived that an elimination of “best before” dates would have at least a somewhat positive impact on their business while 21% perceived that it would have a negative impact.

Food fraud

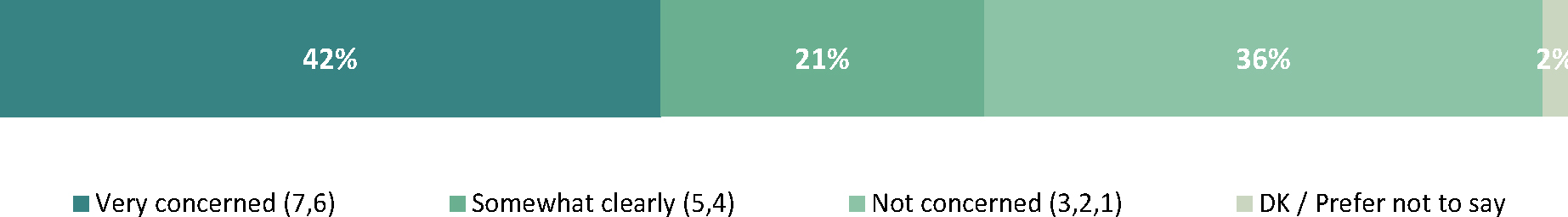

More than two fifths (42%) reported being very concerned with food fraud (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) while another 21% reported being somewhat concerned (scores of 4 or 5). Conversely, 36% were not very concerned with food fraud (scores of 1, 2 or 3).

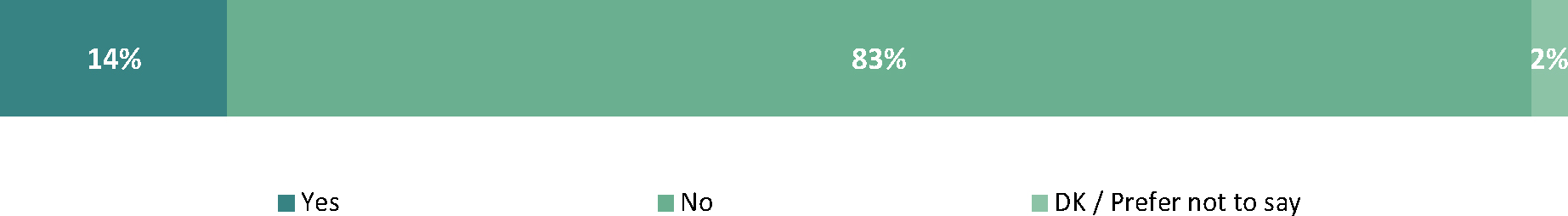

A minority of food businesses (14%) reported being affected by food fraud.

More than two thirds (68%) reported being very likely (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) to report a fellow industry member of suspected food fraud to the CFIA while another 16% would be somewhat likely to report them (scores of 4 or 5). Conversely, 13% reported being not very likely to report suspected food fraud to the CFIA (scores of 1, 2 or 3).

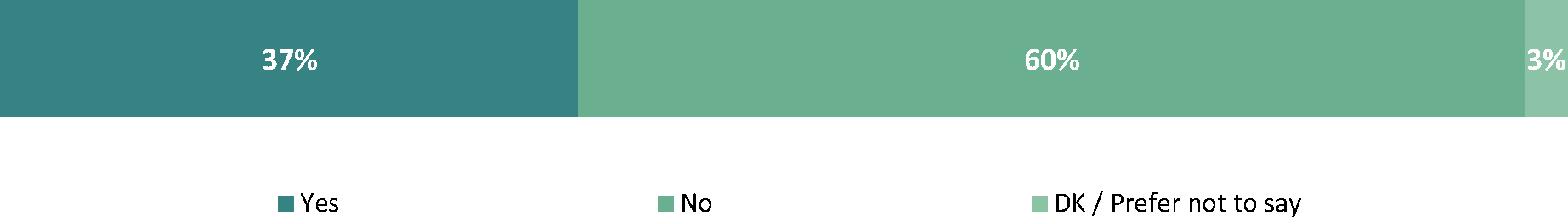

More than one third of business representatives (37%) indicated they knew how to report suspected food fraud to the CFIA while 60% did not.

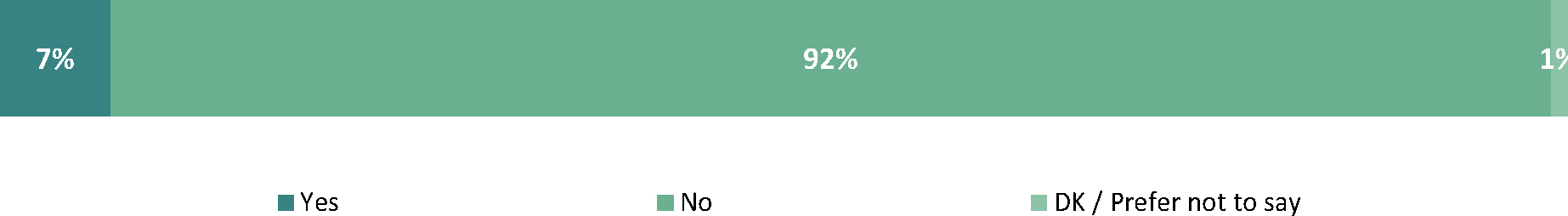

Less than 1 in 10 (7%) reported that their business had received consumer complaints related to food fraud or misrepresented food.

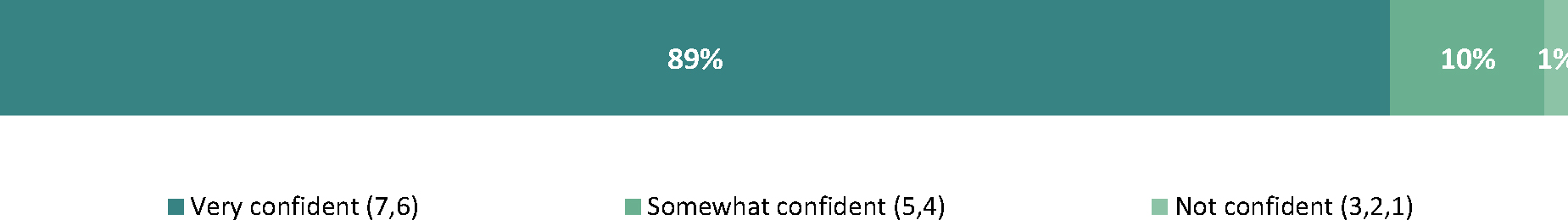

The majority of businesses that sell fish or seafood products (89%) reported high confidence that the fish or seafood products that they sell are properly labelled for the type of fish that they are (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale).

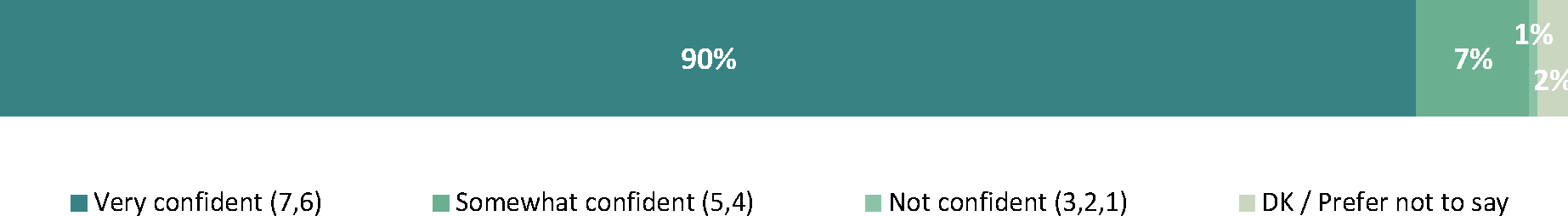

A majority of respondents were very confident (scores of 6 or 7) that all of the food products they sell are properly labelled (90%).

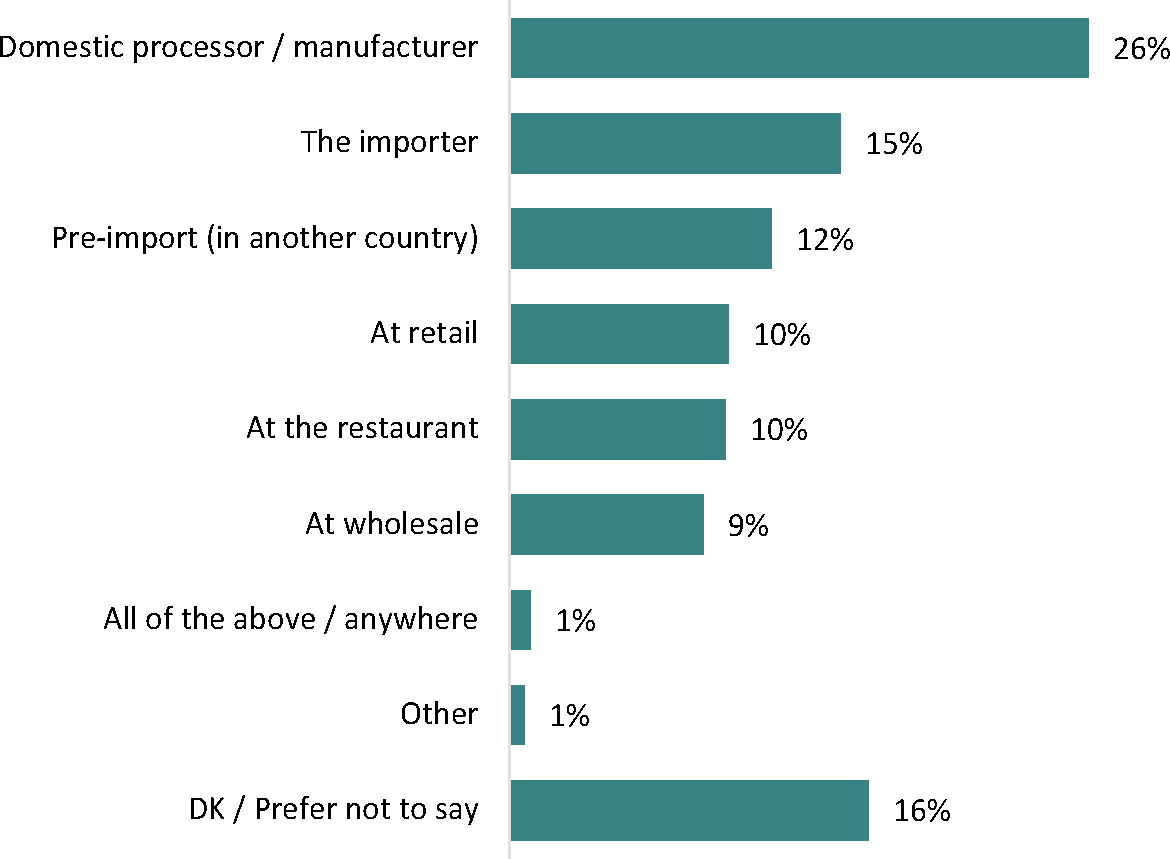

The most commonly suspected source of mislabelling was the domestic processor/ manufacturer (26%) followed by the importer (15%), pre-import in another country (12%), at retail (10%), at restaurants (10%), or at wholesale (9%). Many (16%) were unsure where mislabelling was most likely to occur.

Information search and understanding

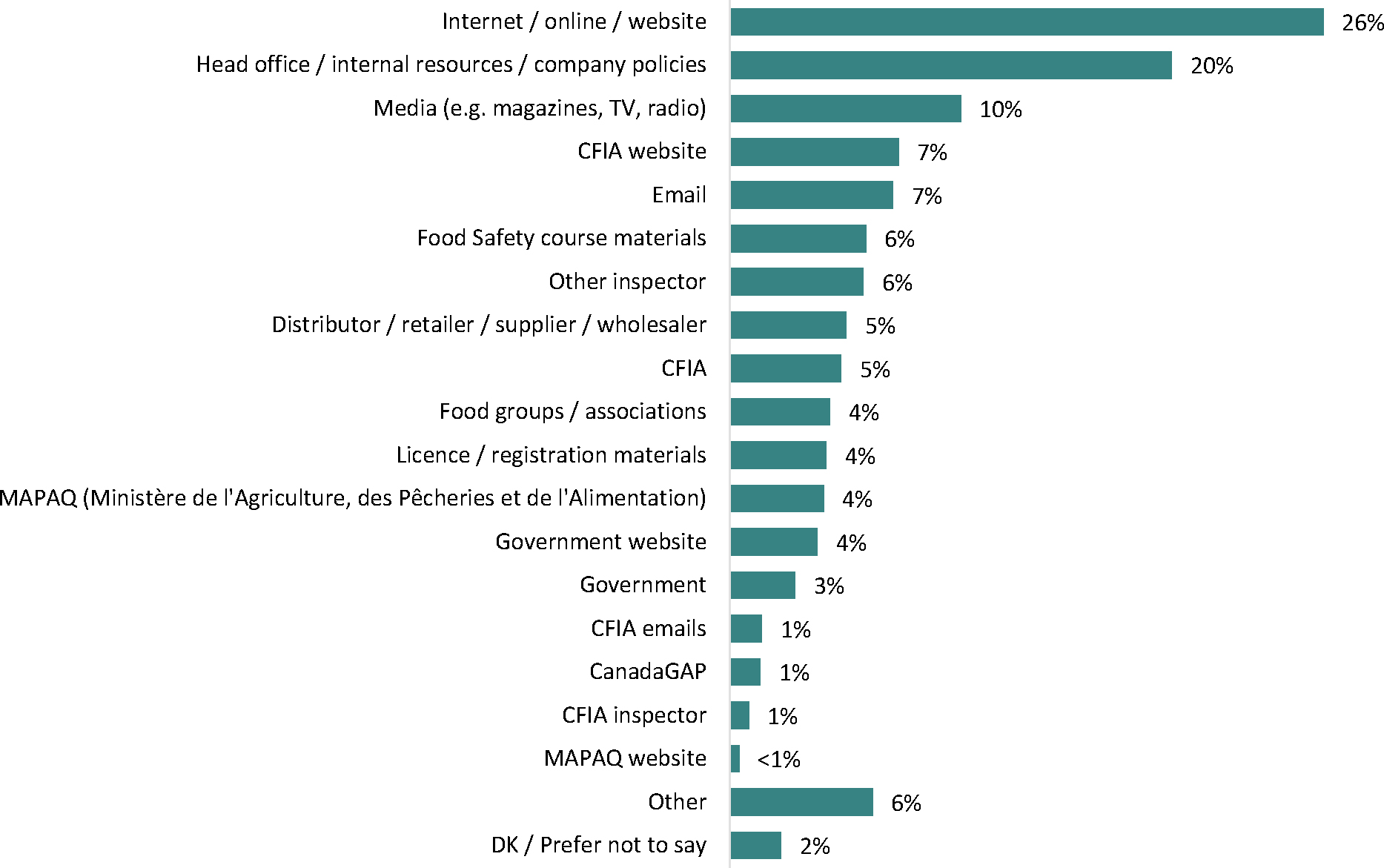

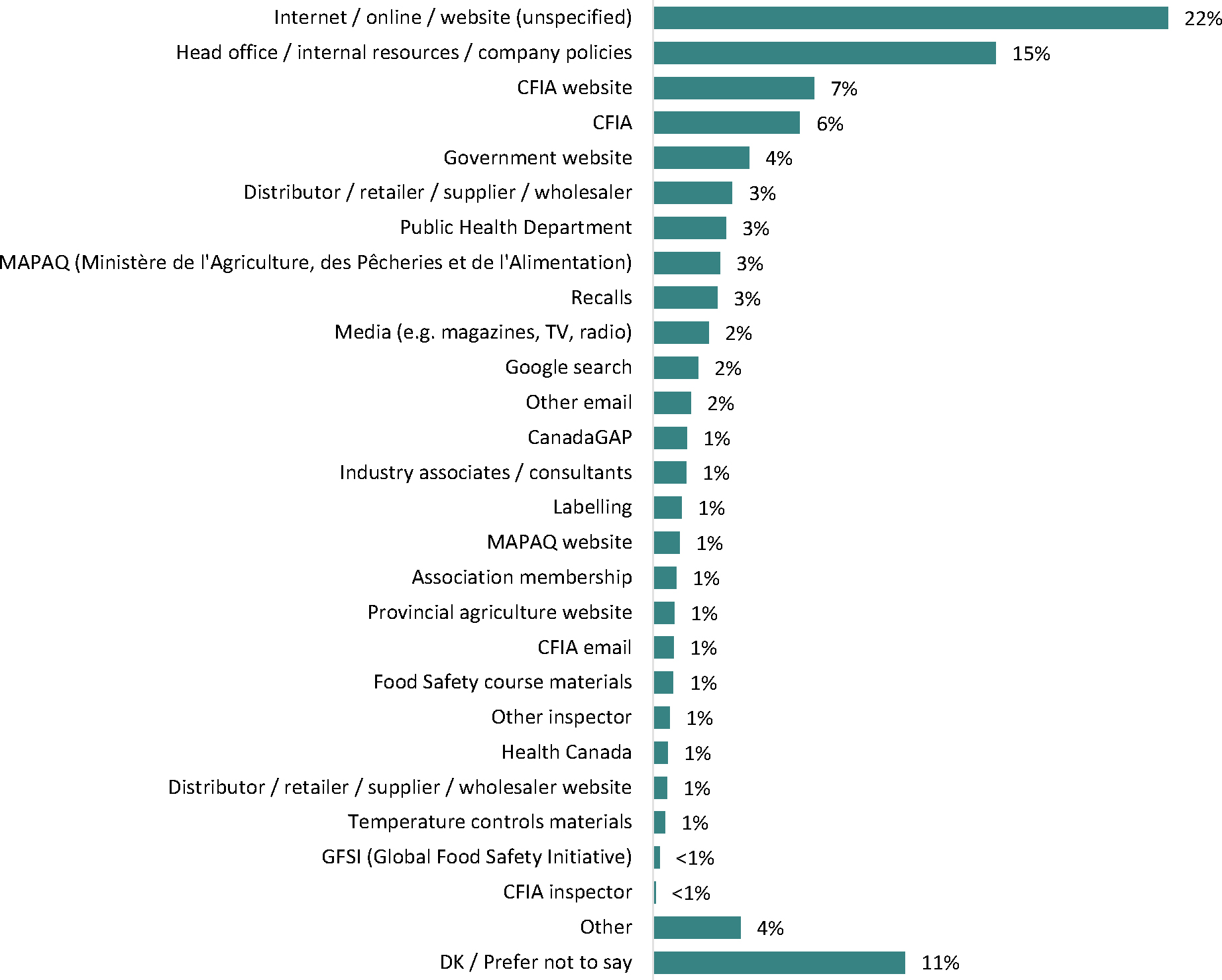

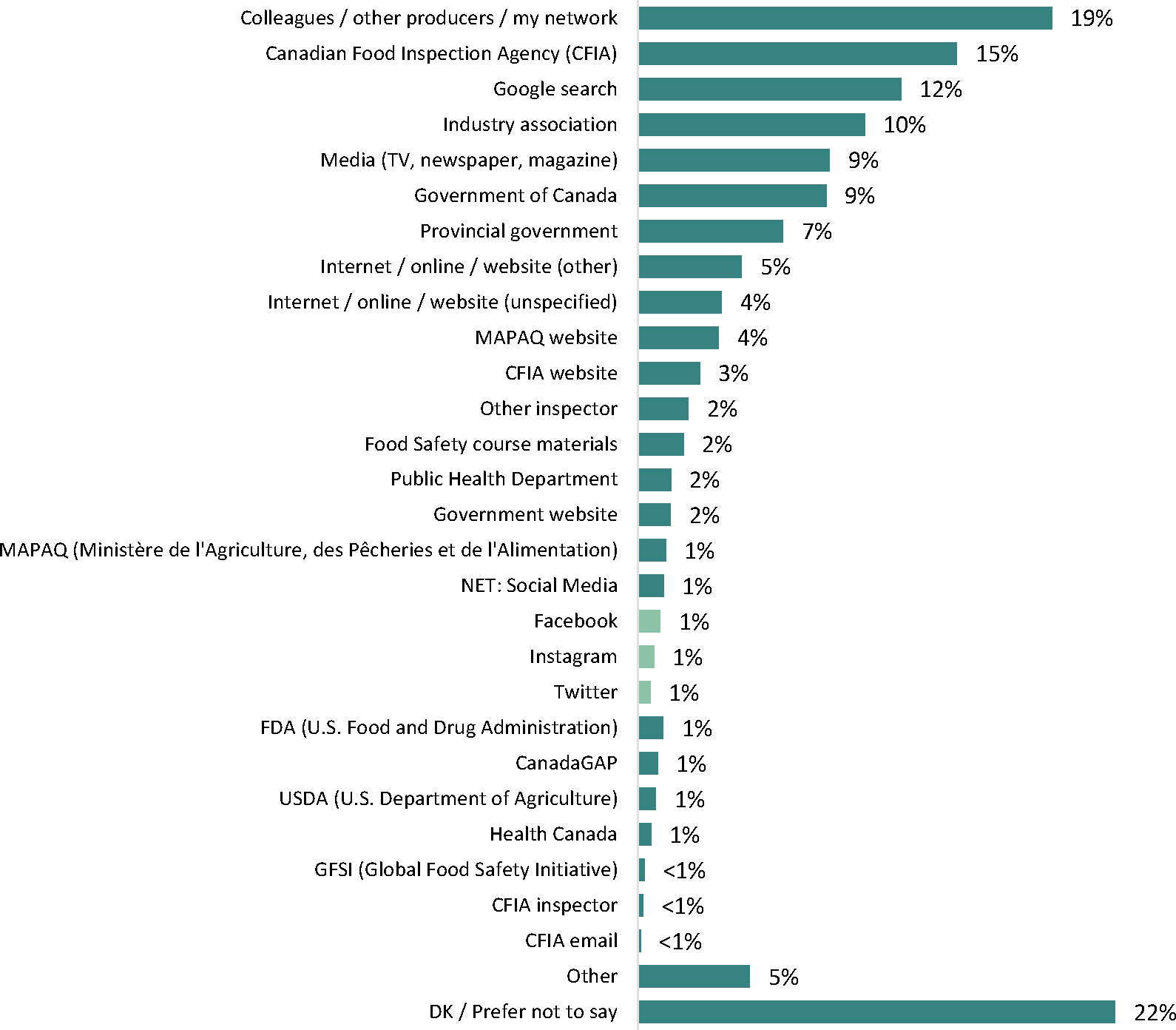

Business representatives most often use the internet as a source of information about food safety regulations or requirements (22%) followed by internal resources such as head office or company policies (15%).

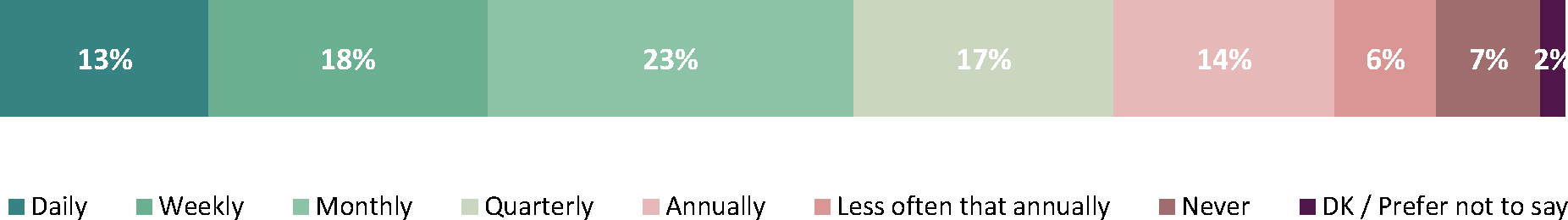

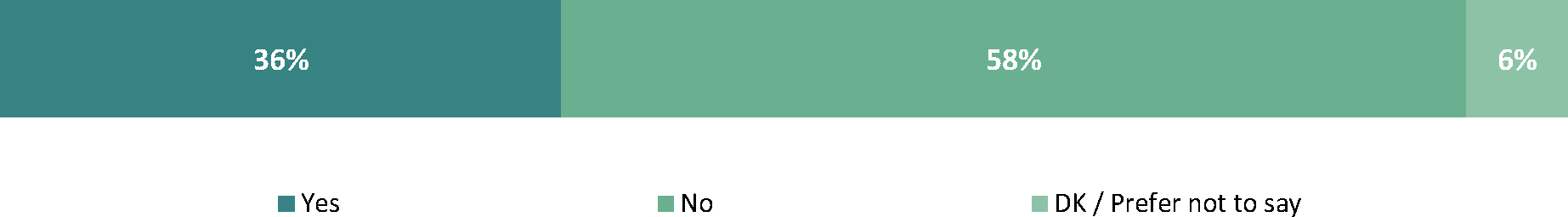

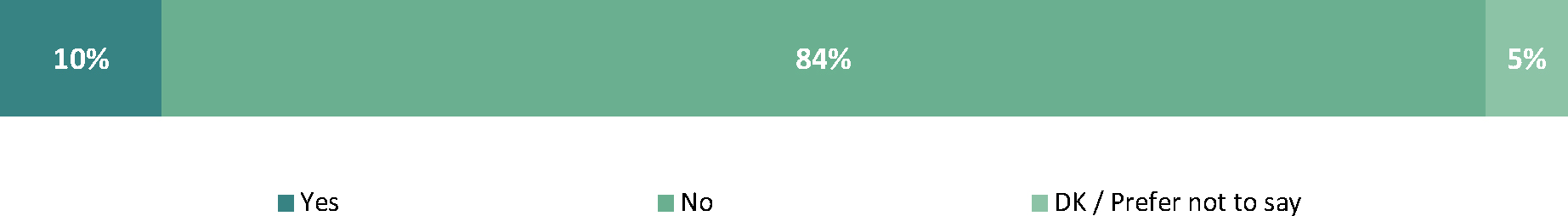

Business representatives were asked whether they had received any information from the CFIA within the past year. More than a third (36%) recalled receiving information from the CFIA while nearly 3 in 5 (58%) did not.

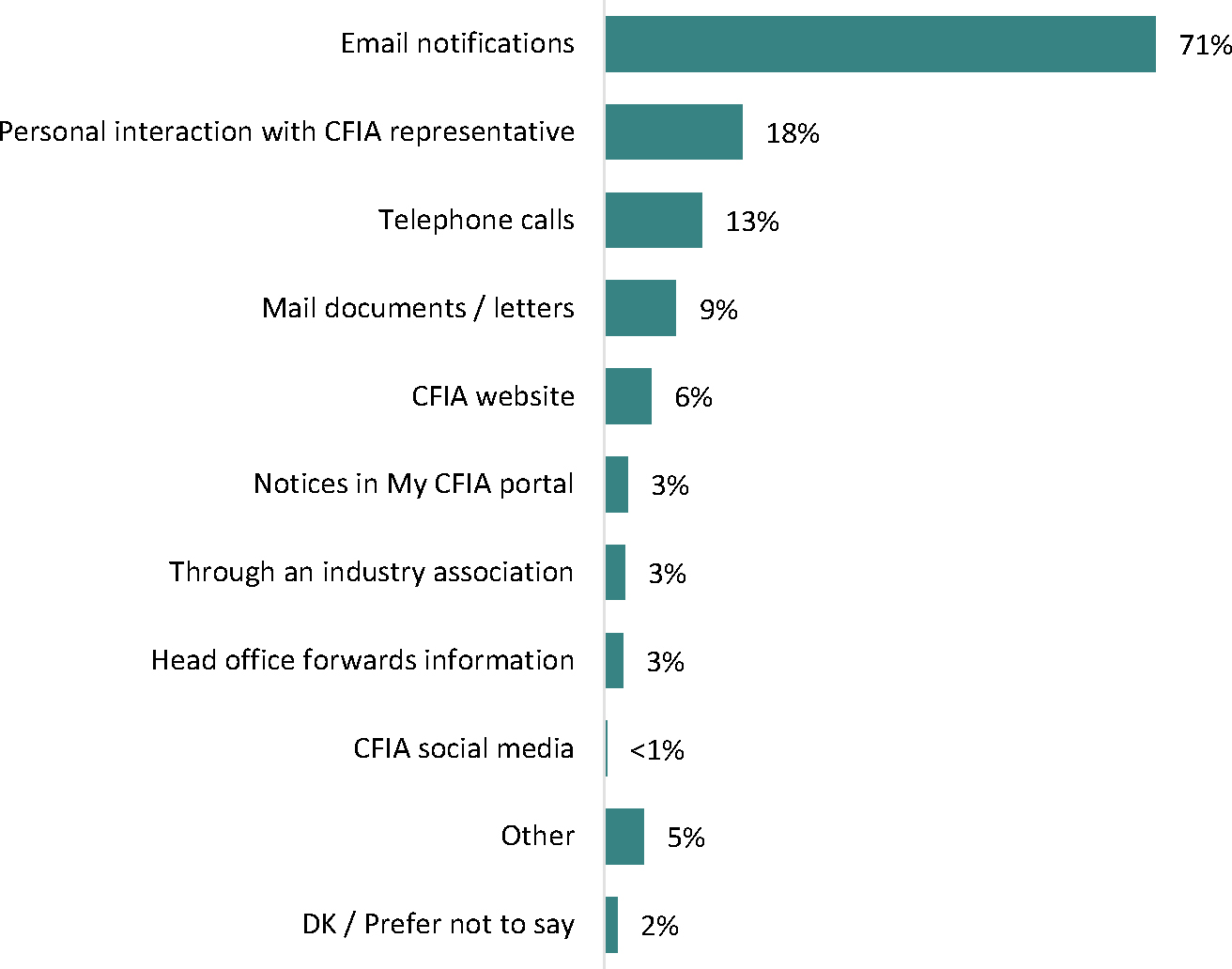

Those who had received information from the CFIA within most often reported receiving email notifications from the CFIA (71%) followed by personal interaction with a CFIA representative (18%) or telephone calls (13%).

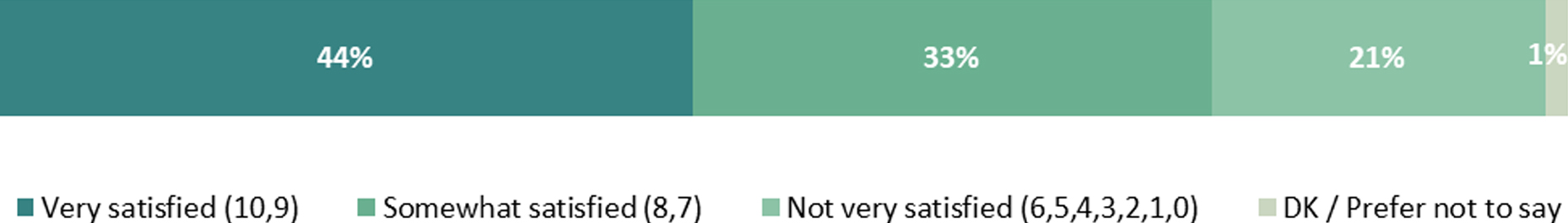

More than 2 in 5 (44%) reported high satisfaction with CFIA communications (scores of 9 or 10 on an 11-point scale) and another third (33%) reported moderate satisfaction (scores of 7 or 8). Conversely, a fifth (21%) reported low satisfaction with communications from the CFIA (scores of 6 or lower).

Other key findings related to CFIA communications included:

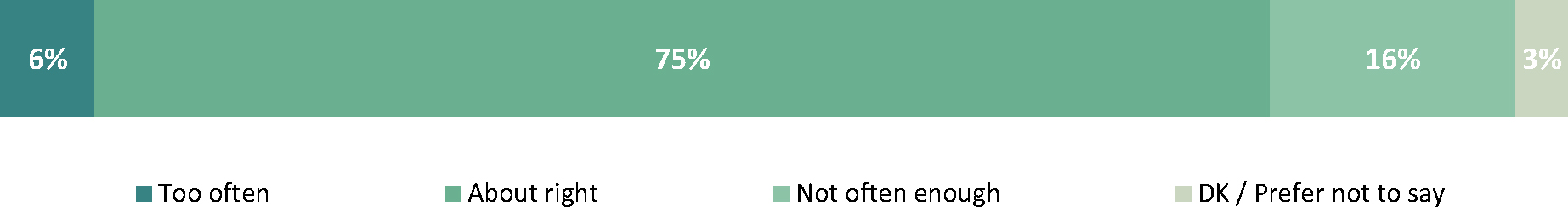

A majority felt that the frequency of CFIA communication was about right (75%) while 16% there was not enough communication and 6% felt there was too much.

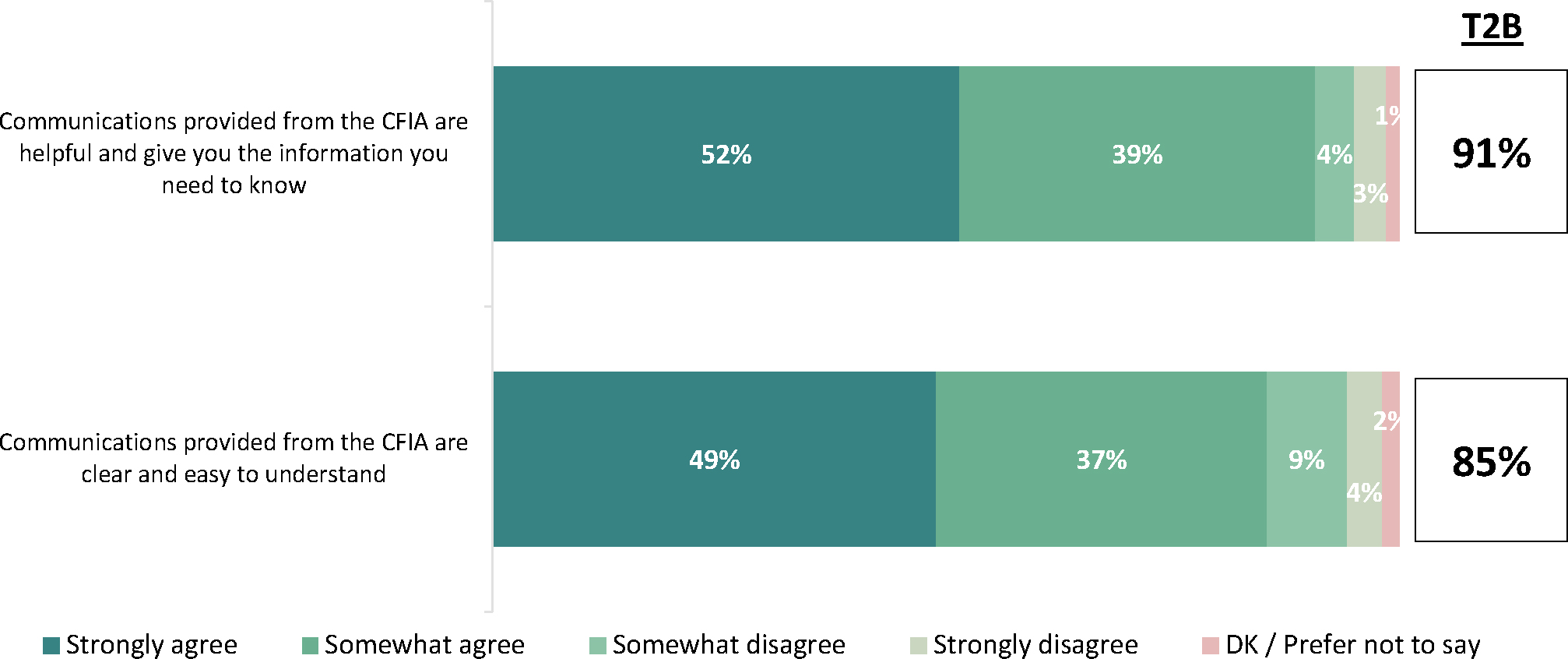

Most business representatives who had received information from the CFIA in the past year (91%) agreed that these communications are helpful and provide the information they need to know.

Similarly, 85% agreed that communications from the CFIA are clear and easy to understand.

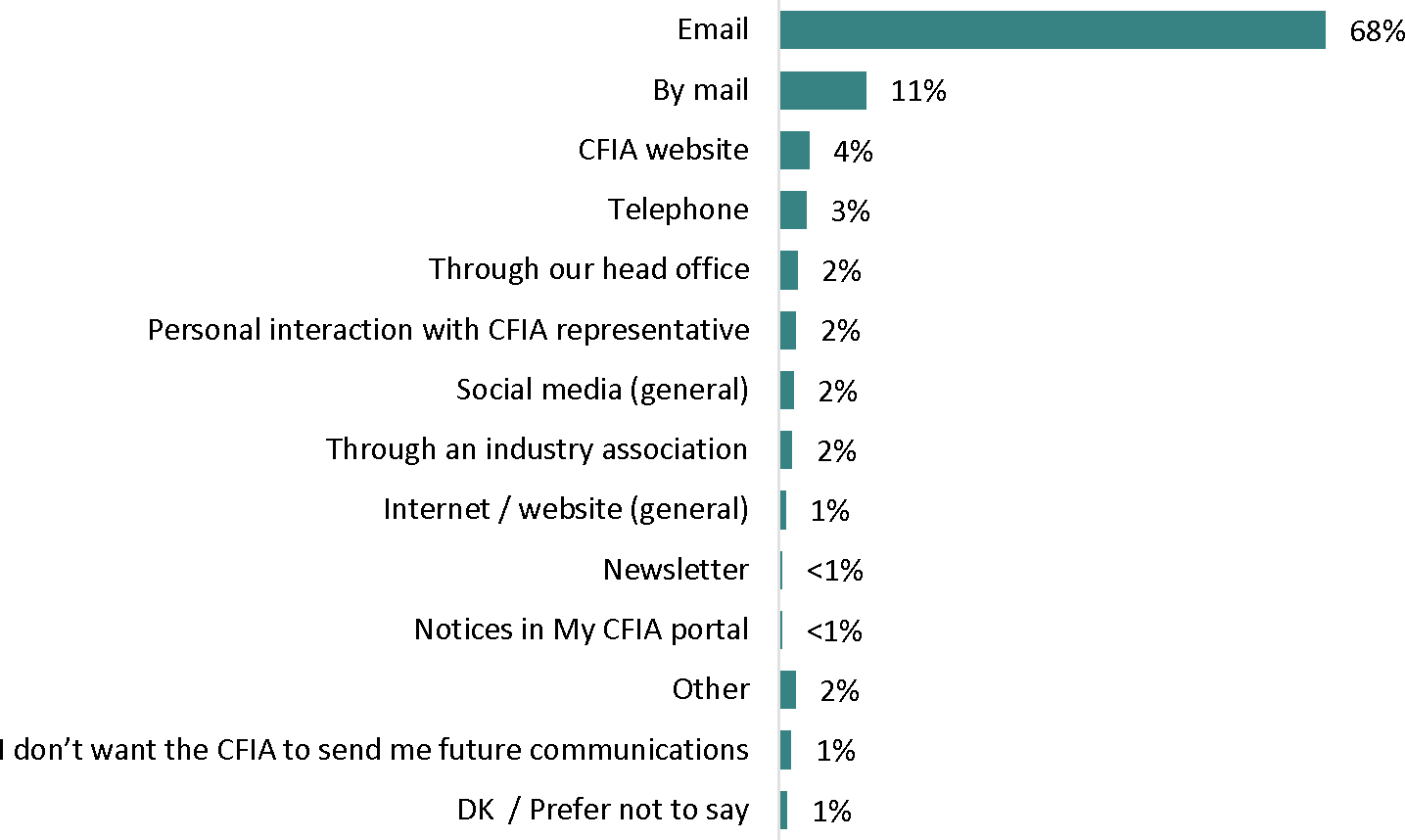

When it comes to receiving communication from the CFIA, email was the most preferred channel (68%) followed at a distance by mail (11%).

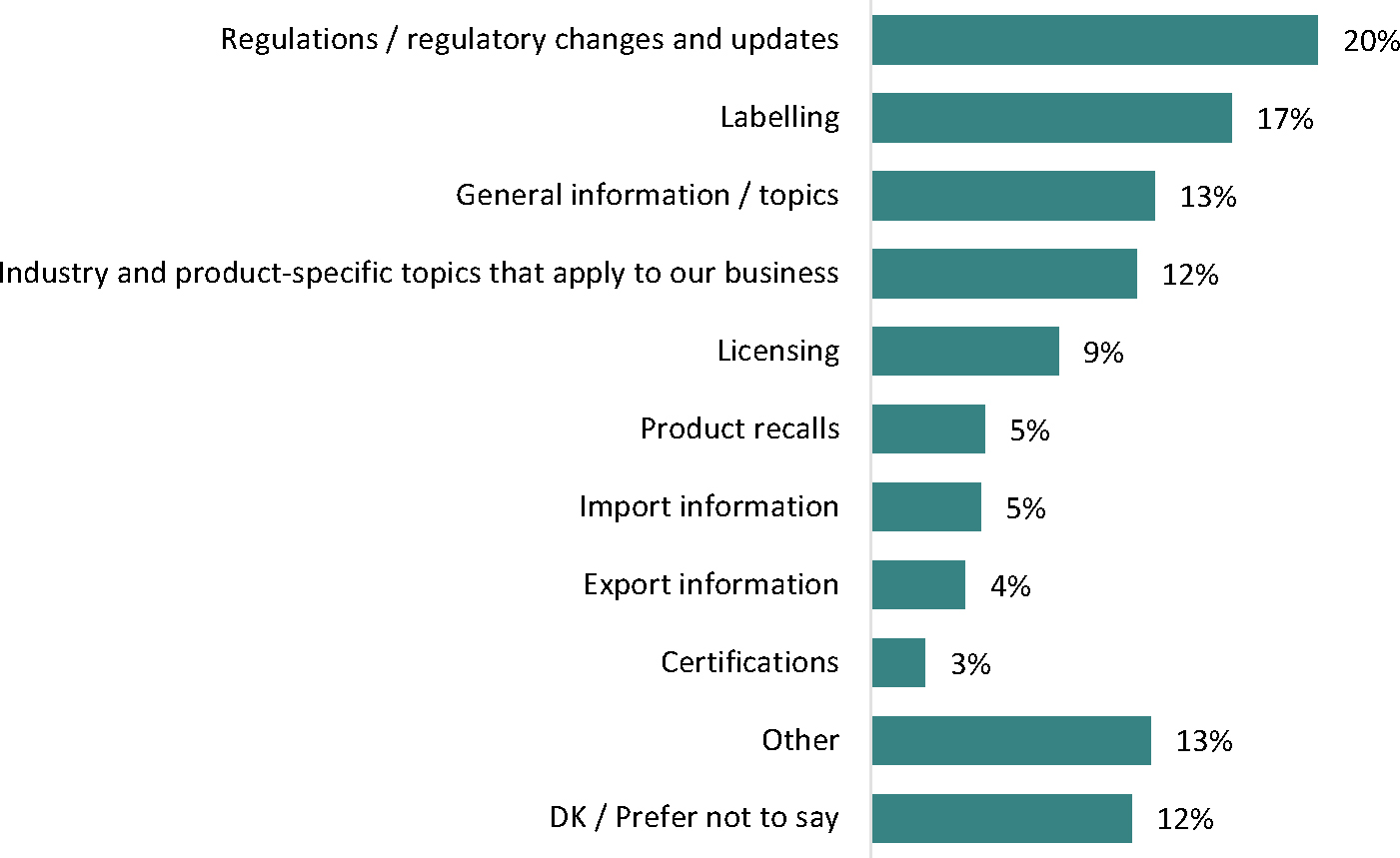

One in 10 (10%) reported difficulties getting the information they needed from the CFIA over the past few years. These respondents most often cited difficulties getting information on regulations or regulatory changes (20%), labelling (17%), general information (13%), and industry and product specific topics (12%).

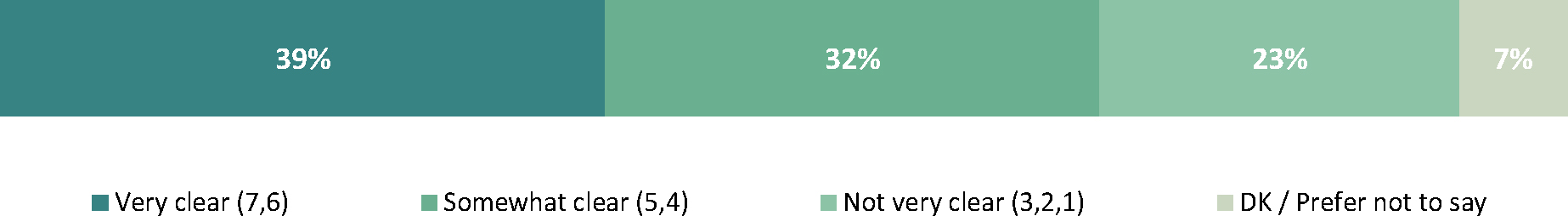

Nearly two fifths (39%) believed that the concept of “outcome-based” regulations was clear to them (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) while it was somewhat clear (scores of 4 or 5) for 32% of businesses. Conversely, 23% felt the concept was not very clear (scores of 1, 2 or 3).

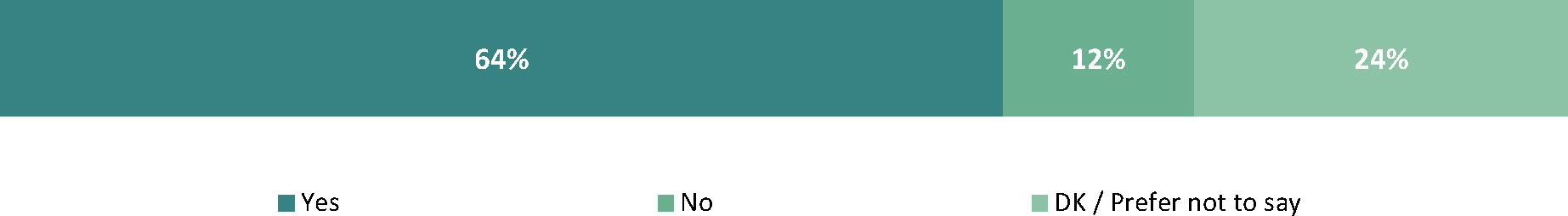

When asked to consider whether the SFCR are “outcome-based” regulations, nearly two thirds (64%) believed so while 12% did not. Nearly a quarter (24%) were unsure.

Ask CFIA

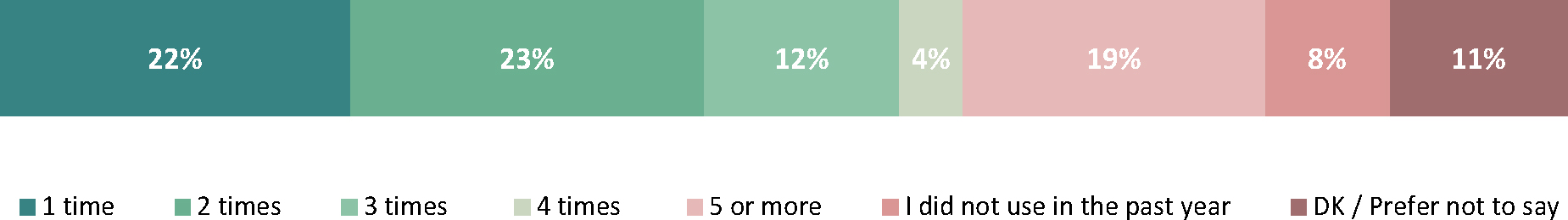

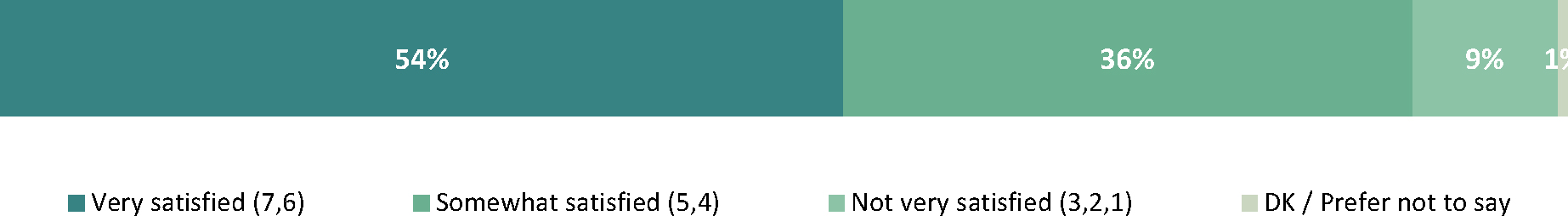

More than 1 in 10 (11%) business representatives reported having used the Ask CFIA service. Of these respondents, over half (54%) reported high satisfaction (scores of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) and more than a third (36%) reported moderate satisfaction (scores of 4 or 5).

These results are presented and discussed in-depth throughout the detailed results section of the report.

Detailed results

Research purpose and objectives

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has a mandate to verify food sold in Canada is safe and accurately represented. The CFIA achieves this through enforcement of Canada’s federal food legislation, including the Safe Food for Canadians Act (SFCA) and its regulations (SFCR) which introduced new requirements for food businesses as of January 15, 2019.

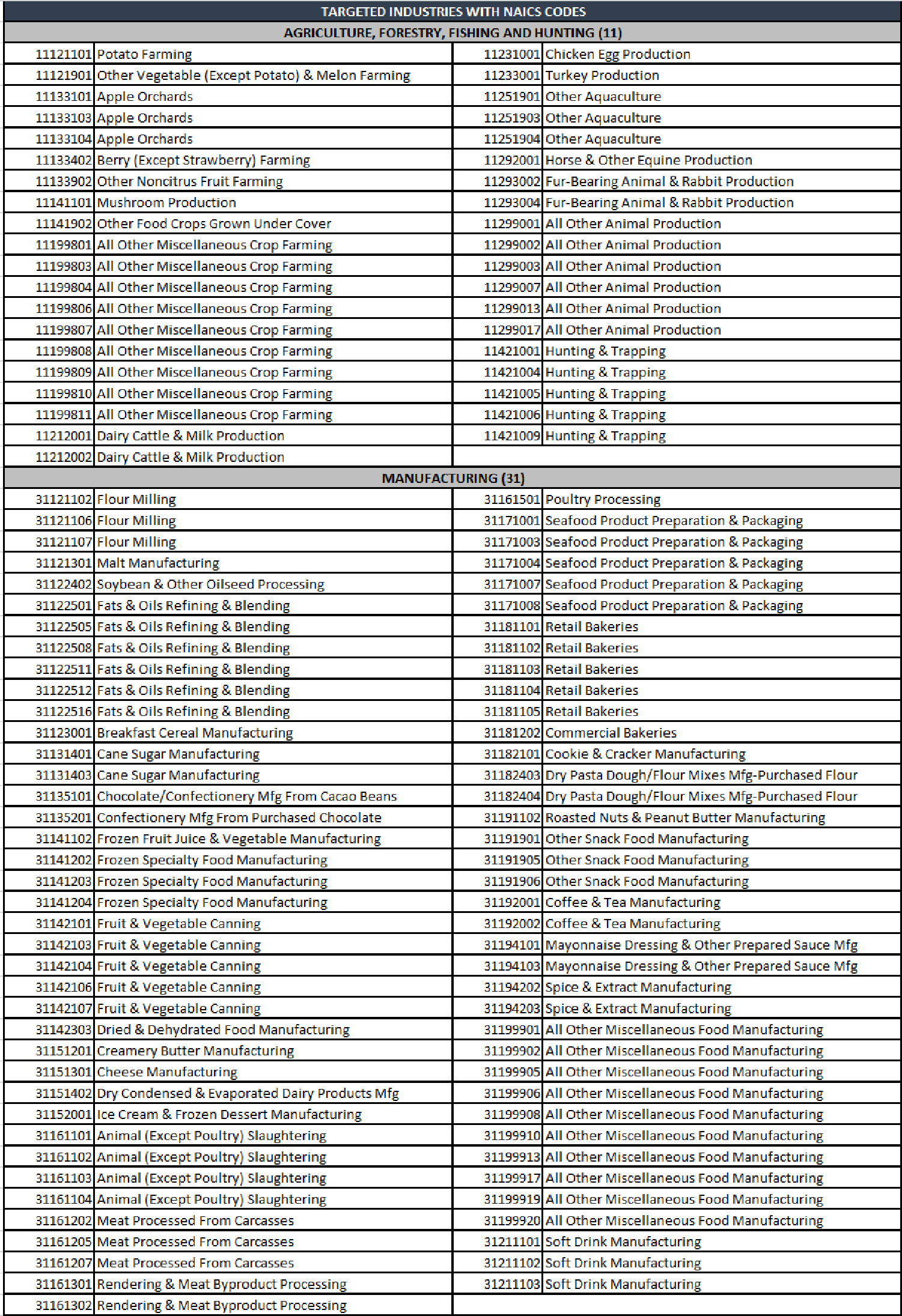

The SFCR generally applies to food for human consumption (including ingredients) that is imported, exported, or inter-provincially traded for commercial purposes. It also applies to the slaughter of food animals from which meat products to be exported or inter-provincially traded may be derived. The regulations had a graduated coming into force schedule that started in January 2019, beginning with businesses that were previously registered under commodity-specific regulations (for example, meat, eggs, fish and seafood, dairy), and ending in July 2020 for businesses in the manufactured food sector. SFCR introduced three fundamental components that apply to most food businesses: licensing, preventive controls and traceability requirements.

Some of the requirements were phased in based on food commodity, type of activity and business size. As of November 1, 2022, the CFIA is conducting compliance activities of the SFCR requirements for all food sectors, including the final sector to be on-boarded – the manufactured food sector (MFS).

A review of the provisions and operations of the SFCA, including an assessment of the resources allocated to its administration and enforcement, must take place every five years. The first review is scheduled to take place in 2024-25.

As part of the CFIA’s commitment to delivering timely information and guidance to regulated parties, the Agency continues to develop tools and services to help industry meet food safety requirements.

Food safety is a top priority for the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. The CFIA continually works to improve the overall health of Canadians. This includes ensuring that food is safely produced, accurately represented to Canadians, and properly labelled.

The CFIA develops and delivers programs and services designed to protect Canadians from preventable food safety hazards, to ensure that food safety emergencies are effectively managed, food is accurately represented, and to ensure that the public is aware of—and contributes to—food safety. Canada has a sound and internationally respected food safety system and food recall process. The SFCR provide clear and consistent rules for food commodities so that consumers can be confident that food on grocery shelves is safe to eat, whether it is produced in Canada or abroad. The regulations also help get unsafe food off the shelves faster by requiring businesses that import or prepare food for export or interprovincial trade to trace their food back to their supplier and forward to whom they sold their products.

In terms of ensuring that food is accurately represented, Canadian law prohibits the labelling, packaging, treating, processing, selling or advertising of any food in a manner that is false, misleading or deceptive to consumers. Food fraud can mislead consumers and is also a food safety issue (for example, if products contain undeclared allergens). The CFIA works to raise awareness of and protect consumers from food misrepresentation by conducting inspections, analyzing food samples and taking enforcement action. Combatting food fraud is a shared responsibility between government, industry and consumers. Since food fraud is meant to deceive consumers, it is not easy to know whether a food is fraudulent or not. Even so, consumers play an important role in identifying and tackling food fraud.

The objective of this research is to gain a better understanding of industry awareness, motivations, perceptions and attitudes about:

The various roles and responsibilities within the food safety system, in particular to measure the level of awareness of their own responsibilities in the system;

Federal food regulations as they apply to online sales and importing;

Resource needs and barriers to complying with regulatory requirements, to identify root causes of non-compliance and support development and implementation of compliance promotion, communications, and support service activities;

Current services and expectations on future services and programs, such as My CFIA;

Specific messaging, including compliance promotion tools and communications products;

The effectiveness and satisfaction of the SFCR communications and related communications from various services, such as My CFIA and Ask CFIA;

How requirements change for businesses may vary depending on demographic characteristics of ownership or clientele;

Satisfaction with guidance received from Ask CFIA and rating of overall experience in using the service; and,

Industry’s opinion on using third-party verification systems.

Additionally, the research will aim to gain a better understanding of the following among consumers:

Awareness and understanding of food safety and food fraud, and how the CFIA addresses them;

Awareness of the CFIA’s online food concern reporting tool;

Trust that CFIA takes enforcement action to protect consumers from food fraud;

Habits and concerns about food safety;

Habits and concerns about best-before dates;

Public trust that fish is accurately labelled and safe to eat;

Sources of information on food safety and food fraud;

Perceptions and concerns about food fraud;

Awareness and effectiveness of CFIA communications regarding food fraud; and,

Awareness and understanding of CFIA transparency regarding food fraud enforcement activities.

Qualitative research results – focus groups with consumers

Overall views on and experiences with food fraud

Defining food fraud

To kick-off the focus groups with consumers, participants were shown the following sentence and asked to provide some examples of what they felt would constitute food fraud.

Food fraud occurs when food is misrepresented.

The topic of product sizes came up often with many mentioning “shrinkflation” (when brands quietly reduce the size of their products but continue to sell them for the same price). Many also discussed how the weight listed on a product package can sometimes be greater than the actual weight of the contents in the package.

Many gave examples of misleading labelling, such as:

Products that claim to be “natural” or “healthy” but contain several “unhealthy” or artificial ingredients.

Items labelled as made with real fruit but are actually only made from a small percentage of real fruit in addition to artificial flavours.

Fish products that are farmed, but do not specify origin on package.

Meat that is mechanically tenderized but does not say so on package.

False claims of packaged products (for example, natural health products).

A smaller proportion of participants considered the following food fraud:

Fruits and vegetables or other products labelled as organic when they are not.

Dairy, meat or egg products that are labelled as “free-range” when they are not.

Fish products that are labelled incorrectly (for example, salmon that is actually another type of fish, calamari or mussels that are actually another type of fish or seafood, canned tuna that contains other types of white fish).

Products being labelled as 100% pure when they actually contain a mix of ingredients or use cheaper or artificial ingredients as filler.

After participants listed examples of what they thought may be classified as food fraud, the moderator specified that food fraud is classified as intentional misrepresentation of food.

Sources of information on food fraud

When asked whether they had seen, heard or read anything about food fraud in the past year, some recalled examples from social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or Reddit, the news, documentaries as well as friends and family. Some examples included the following:

Side-by-side images of product packaging before and after “shrinkflation”.

A Reddit post where someone purchased pancake mix and weighed the contents to find it was smaller than what the packaging listed.

Olive oil listed as organic when it was not actually, or labelled as pure olive oil when it actually contained a mix of oils.

Honey that is labeled as pure but has been diluted with cheaper ingredients.

Maple syrup that when tested, was not 100% maple syrup.

Salmon from grocery stores that was tested and determined as misrepresented and in reality, was another form of fish.

Calamari and mussels sold at high price points when they were actually less expensive types of fish being misrepresented.

Water being added to meat in order to inflate the size.

Artificial colouring being added to products such as salmon or jam to make them appear more appetizing and attractive to consumers.

For the most part, participants did not actively look for information on food fraud but rather came across news articles or posts on the topic. Only a few said that they searched for more information after learning about examples of food fraud through the news, documentaries or social media.

Level of concern with food fraud

When it comes to purchasing food products from grocery stores, most participants were not overly concerned about encountering food fraud and said this was not something they were actively looking for. With that said, many explained that they were cautious in general when purchasing groceries from a health-perspective or to get good value for their money.

Those who were more concerned with food fraud tended to be those with a food allergy or dietary restriction in their household as well as those who were health conscious. These participants tended to pay closer attention to ingredient lists and nutrition labels to ensure that the products they are buying are suitable for their dietary needs.

When asked which foods they felt were more subject to food fraud, animal products came up the most. Participants typically described skepticism in labels such as “organic”, “natural”, “free-range”, “grass-fed”, “triple A” or “halal” with the reasoning that they would not be able to distinguish if these products actually met these claims. Some had similar concerns regarding “organic” labelling on fruits, vegetables or packaged foods.

Some felt that processed or packaged foods may be subject to food fraud as it would be easier for companies to add cheaper ingredients as a way to save costs and consumers likely would not notice.

A few participants shared that while they have always been skeptical about companies being misleading or dishonest about the quality or ingredients in their products as a way to cut costs, they are slightly more concerned recently due to the economy.

When specifically asked about fish sold in Canada, most said that they trusted that it is for the most part, properly labelled as they had no reason to believe otherwise.

Of those who were less trusting, a handful had heard about fish being mislabelled from the news or other sources which decreased confidence. Others were worried about mislabelling from a sourcing standpoint. For example, some wondered whether a product labelled as wild-caught might actually be farmed, or whether a product labelled as a product of Canada might have actually been caught in another country and simply packaged in Canada.

“I’ve read some articles recently in different news outlets about fish mislabelling. I believe there was a case of it happening at [a grocery store] in Halifax […] some salmon was apparently not salmon. I’ve heard that it is a phenomenon that fish can be misrepresented or mislabelled. I do still eat the fish but I kind of accept that it might not necessarily be what I think it is.” – Female, 30, Nova Scotia

Some felt that fraud would be more likely to occur in packaged fish such as canned tuna or fish sticks, which may use a mix of less expensive fish rather than the type of fish listed on the package and consumers would be less likely to notice the discrepancy.

A majority of participants agreed that the fish sold in Canada is safe to eat, including most of those who were less trusting that fish was labelled correctly. Rather than concerns about food fraud, concerns about safety of fish mainly pertained to its freshness, as many referred to the distance it may travel before it gets to the grocery store. A few also mentioned slight concerns about mercury levels. However, those with concerns explained that they view it more as a quality concern rather than a safety concern and continue to eat fish.

When participants were asked to guess what percentage of fish sold in Canada was accurately labelled, responses typically ranged from 40%-80%, although many admitted that they had not thought about this before, and the topic of discussion made them perceive that fish mislabelling might be a bigger issue than they were aware of. Participants were informed that 92.7% of fish sold in Canada is properly labelled, which many felt was great to hear and would lessen concerns. While most were reassured, a few questioned how this statistic was calculated and what would explain the remaining proportion of fish that is not properly labelled.

“I think it’s pretty good. But I do have questions about the other 7%, and what exactly that means and what is being done about it?” – Female, 33, British Columbia « Ils disent 92%, mais comment ils ont fait pour vérifier pourquoi ça ne serait pas 100%? Comment ont-ils fait pour quantifier le 92%, c'est la question qu'il faut se poser. » – Male, 30, Quebec [« They say 92%, but how did they figure out it wasn't 100%? How did they quantify 92%, that is the question. »]

Participants were generally unsure at what point in the fish supply chain they believed fraud might occur, however some suspected this probably happened at the processing or packaging plants.

Personal experiences with food fraud

Overall, very few participants had personally experienced food fraud. That said, some admitted that they might not know if they had encountered or consumed a product that was fraudulent.

Of the few who felt they had experienced food fraud, the following examples were shared:

Cereal which contained an ingredient not listed on the box.

Product weight inconsistent with weight listed on package.

Product listed as a prepared meal with beef but was mainly comprised of soy protein and a smaller percentage of beef.

“Lean” ground beef which had a lot of fat after cooking, suspected to not be lean meat.

As a result of suspected food fraud, some participants said they chose not to purchase the product (if they noticed the issue in the store), did not buy the product again, did not consume the product out of concern for potential allergens, returned the product to the store, or emailed the company. None of the participants indicated having reported their concern with a government agency such as the CFIA.

If they were to encounter food fraud in the future, their actions taken would depend on factors such as the severity of the fraud, where they purchased the product, the amount of money they spent on the product, whether there had been any impact on their health, and the quantity of the product they purchased.

Many participants suggested they would return the product to the store they purchased it from to try to get refunded, especially if it was an expensive item. Otherwise, some said they might “cut their losses” if the item was not particularly expensive in order to avoid having to spend time taking the item back or contacting the company. Others would look on the package for a contact number where they could communicate the issue to the supplier/manufacturer directly. A few would search online to see if other people had similar experiences or would discuss the issue with friends and family and, depending on the health consequence or financial toll, they may recommend to others not to buy the brand or product.

If the fraud resulted in a health consequence such as food poisoning or an allergic reaction from an undisclosed ingredient, participants would be much more likely to take action, especially as it could prevent others from getting sick. In these cases, a couple of participants suggested that they may look up the government department that handles these complaints. However, if the encountered food fraud was something such as a minor labelling issue, many would brush it off or take less extreme actions such as contacting the store.

When asked what consequences they would expect if a company was found guilty of food fraud, many would want there to be an investigation to determine if the issue was widespread. Participants would want to see transparency in the process and for the companies responsible to be held accountable through financial penalties and bad press so that Canadians are made aware and can make informed choices on which brands and products to buy in the future. A few suggested that the amount fined should be commensurate with the size of the company, otherwise large companies may not be sufficiently impacted financially and might repeat the offense.

Views on how food fraud is managed in Canada

Participants were asked their opinion on how food fraud is managed in Canada. For the most part, participants felt that it is well managed and that overall, there is a high level of confidence that food in Canada is safe to eat, especially compared to some other countries. This sentiment came from the fact that in most groups, none or very few participants had experienced food fraud, or knew somebody else who had. Additionally, a few mentioned that when food safety issues occurred, as seen through food recalls, actions are quickly taken to inform Canadians and pull these products from shelves, which gave them reassurance.

Most assumed that there is a government agency responsible for managing food safety, however only a few mentioned the CFIA organically. There was some general agreement that there should be more awareness of the topic of food fraud, how the government is managing the issue as well as what to do if you encounter it. Some mentioned that they would be unsure where to report food safety issues or food fraud if they were to encounter it.

A few felt that the way food fraud or food safety in general is managed in Canada is good but could be improved. These participants typically had concerns about the length of time it can take for issues to get caught. A couple mentioned having seen news articles about food companies that were not following regulations, and when they looked into these articles, they found that the investigations had started years prior. For these individuals, this lowered confidence when it comes to how quickly food safety or food fraud issues are identified and then resolved.

Awareness of CFIA’s involvement in food fraud

Participants were informed that the CFIA is responsible for regulating food in Canada and verifying that companies are complying with the federal food rules.

While many had heard of the CFIA before, very few had ever thought about contacting the CFIA when they encountered food fraud or a similar food safety issue. Instead, they typically thought of contacting the store or the manufacturer.

As well, many repeated that they did not know much about food fraud in general so they had not thought about who they would contact if they were to encounter it. Those who had not had personal experiences with food fraud also felt they would probably think about contacting the store or contact the company directly rather than contacting the CFIA.

Many were apprehensive about contacting the CFIA regarding food fraud with concerns that it would probably take awhile to get a response, or it might not be worth the effort, especially if it was just a mislabelling issue rather than a food safety concern. There were also various concerns that engaging with a government of Canada agency would be cumbersome and time consuming which in turn would discourage some from considering this reporting avenue. However, if the food fraud was to result in a health consequence, more would consider contacting the CFIA.

“If it wasn’t severe, or health threatening or anything like that, I don’t think it’s necessary to take it that far. Maybe when it is health threatening, you know this is not just about getting your money back, you don’t want this to happen to somebody else, they should take this out of stores. Maybe then you’d be at the point to actually contact them.” – Female, 23, Manitoba

Additionally, some said that that they would first contact the store or manufacturer, and if unsatisfied with the response or actions taken, they would then contact the CFIA.

With that said, some felt that it was good to know that the CFIA could be a contact for food fraud concerns, as some explained they would trust a government department or agency to do more to look into the actual issue than the store where the product was sold or the manufacturer. These participants felt that there should be more awareness about the CFIA’s role in food safety and food fraud so that consumers know what actions to take if they experience it.

“I think the problem is that it’s not something that you really hear that much about. So, you don’t really know what the avenue is to do anything about it. Personally, I don’t know where I would go to report it, apart from complaining to the store or the company. I don’t even know what regulations are around it.” – Female, 65, Prince Edward Island

Participants were then shown the following screenshot of the CFIA’s online food concern reporting tool:

The screenshot shows a web page from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) intended to guide users on how to report a food complaint or concern

Here are the details presented on the page: Header: The top of the page includes the Government of Canada logo, and a menu bar that offers navigation options such as the home page link for Canada.ca and specific sections for the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and food safety for consumers. Title: “Find out where to report a food complaint or concern” Instructions: The page provides an interactive form where users are asked to answer a few questions to determine if their complaint should be reported to the CFIA or directed to a provincial, regional, or municipal authority. Important Note: A cautionary note indicates that the CFIA cannot provide medical advice. If the food issue has caused illness, users are advised to seek medical attention. Residency Question: There is a specific question asking if the user’s permanent residence is in the province of Quebec, noting that this information is required. Language Option: A button to switch the language to French (“Français”) is available at the top right corner of the page. This tool is part of the CFIA’s effort to streamline the process of reporting food-related issues and ensuring that concerns are directed to the appropriate authority.

Very few had seen or heard about this tool before. Of the few who had, some stumbled across it when searching for other food safety related information online, however they did not actually use the tool to report a concern or complaint.

The reporting tool was perceived by participants to be beneficial, however some felt that there should be more awareness about it. It was also suggested that in order to instill confidence in its effectiveness, the CFIA could promote the tool along with how it is being used to conduct investigations and prevent food fraud.

Views on food recalls

When participants were asked how concerned they were with food recalls in general (meaning, whether they were on high alert for recalls or do not pay much attention to them), responses varied from low to high concern.

Of those who were less concerned, many shared that the food items they have purchased in the past had never been recalled. Others shared that their low concern for food recalls came from their perception that quality control and standards were typically quite high. A few also had the impression that many recalls were voluntary and from a place of caution rather than because of a serious health concern.

“The reason why I’m not super worried about it is because generally I feel like a lot of recalls are done out of an abundance of caution, and it’s rare that a large number of people get really sick.” – Female, 33, British Columbia

Those who were moderately concerned with food recalls typically said that they do not actively look for recall notices, however when they happen to come across food recall notices, they will pay attention or see which items were affected.

“If I see something, I’ll look into it and make sure I try to, you know, learn what’s happening. But I’m not going to be actively looking for it everywhere I go.” – Male, 42, British Columbia

On the other hand, a few who said they were quite concerned with food recalls had purchased items in the past that had been recalled and worried about the health consequences, with a few explaining that they have had food poisoning in the past. A few also said that they will proactively search for food recalls every once in a while.

“I’ve had food poisoning, and I don’t want to ever have it again […] I pay attention to articles. I’ll share them with my family, my mother who’s elderly. I’m really aware of produce, and you know, kind of e-coli infiltration. And I’m just always looking. I mean, I’m not like crazy paranoid, but if I see an article I’m following it.” – Female, 34, Prince Edward Island

Finally, some participants shared that their concerns regarding food fraud were mostly related to protecting their children.

“I’ll always look over any kind of popular children’s product to make sure there’s no recalls on that […] I can consume things that might be moderately damaging, and I don’t care. But if anything affects my children, I’m far more concerned.” – Male, 37, British Columbia

Participants typically learn of food recalls from the news (some mentioned CTV, Global News website, CBC and CBC’s Marketplace or local newspapers), social media, from signage or information boards in grocery stores, or from friends and family. A handful of participants said they received email alerts. As well, a few mentioned being contacted by a grocery store when a product they purchased had been recalled (Costco was often mentioned in this context).

There was a perception among some that it is harder to get information on recalls than it used to be as many do not watch televised news and either don’t have social media, or do not see news-related information on social media anymore.

Only a small number of participants were aware of email alerts prior to the discussion.

“I recently learned about the government of Canada’s recall email subscription you can sign up for I learned about when I was at school talking about medical devices that were recalled. And I learned that you can sign up via email and you get a newsletter pretty much every day from the Government of Canada with any products at all that are called food or otherwise. A lot of times. It’s auto parts and cars. But I do often read them to be aware of things that might affect me like food.” - Female, 30, Nova Scotia