|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Images of gambling in film

Nigel E. Turner, Centre for Addiction and

Mental Health,

E-mail: nigel_turner@camh.net

Barry Fritz,

Masood Zangeneh,

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health,

Abstract

This article examines the depiction of gambling

in recent films. Often gambling is portrayed either very positively or very

negatively. The authors found eight overlapping themes represented in these

movies: (1) pathological gambling, (2) the magical skill of the professional

gambler, (3) miraculous wins as happy endings, (4) gamblers are suckers, (5)

gamblers cheat, (6) gambling is run by organized crime, (7) the casino heist,

and (8) gambling as a symbolic backdrop to the story. These themes suggest

that the portrayal of gambling in movies has a number of interesting

distortions. The discussion centres on how these distortions have an impact

on efforts to accurately disseminate information about gambling to the

general public.

Keywords: distorted images of gambling in

films, movies about gamblers, exaggerated skill, misinformation

Introduction

Gambling is the act of risking the loss of

something of value (usually money) on an uncertain outcome in the hope of

winning something of greater value (usually money). Gambling has often been a

popular topic for myths, operas, books, songs, and in recent years, motion

pictures. The current article examines images of gambling in motion pictures.

The portrayal of gambling in movies is complex and shaped by social,

historical, and cultural events and processes. While not all films that

include images of gambling are 'about' gambling, many include characters that

engage in some form of gambling activity.

Most people gamble as a means of

entertainment. However, according to Shaffer, Hall, and Vander Bilt, (1999), between 1.35% and 1.85% of the population

in

North America

develop a clinically

significant gambling pathology. Pathological gambling (PG) is an

addiction-like disorder. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (DSM-IV)

(American Psychiatric Association,

2000), lists PG as an impulse control

disorder that is characterized by persistent and maladaptive gambling

behaviours that have disruptive consequences on familial, occupational, and

social pursuits. The availability of gambling has varied over time from unrestricted

gambling to prohibition and back again (see Asbury, 1938; Rose, 1986). Over

the past 20 years there has been a tremendous increase in the availability of

gambling opportunities around the world (Room, Turner, & Ialomiteanu, 1999; Shaffer, Hall, & Vander Bilt, 1999).

According to Dement (1999), the

number of films that depict gambling has also varied over time. As shown in

Figure 1, between 1908 and 1930 only six films about gambling were produced.

However, during the depression and again after the end of World War II,

gambling became a popular subject in movies. In the past 10 years there

appears to have been an increase in the number of gambling-related movies.

Figure 1. Release dates for the movies reviewed in this article and for movies listed in Dement (1999)

Dement's (1999) book, Going for Broke is a thorough examination of movies that depict

pathological gambling. He examined a number of films in terms of the extent

to which the portrayals delivered accurate and appropriate messages about

problem gambling. Although some movies accurately portray the nature of

pathological gambling at least during some segments, Dement found that many

movies about pathological gambling had irresponsibly happy endings. Film images

in some cases reflected societal views on gambling. However, images in films

may also alter societal views of gambling (Dement, 1999). According to social

theory theory (Bandura,

1977), people learn by observing the behaviour of other people and the outcomes

of those behaviours. For example, it is commonly believed that images of

smoking in films may have encouraged people to smoke (Sargent,

Social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) would suggest that this might also apply to media images of gambling (see also Tremblay, Hoffman, & Drabman, 1998). For example, irresponsibly happy endings in movies about pathological gambling could encourage problematic gambling. It is therefore important to examine the images of gambling presented in films to determine what distortions are present in recent movies.

Dement focused only on movies that were about

problem and pathological gambling. Many films that depict gambling or have

images of gambling that are not about pathological gambling per se. In this

article we will extend Dement's work by looking

more broadly at films about gambling. The purpose of this article is to

examine gambling images in motion pictures and to find general themes that

are common across a number of movies. We examine how gambling has been

depicted in recent films, and explore the messages about gambling in these

films. One key topic will be the exploration of misinformation about

gambling.

Gambling is a well-established recreational

activity and it is not surprising that it makes its way into movies. The

first and second authors are recreational gamblers who play poker and enjoy

watching movies about gambling. For balance, the third author is a

non-gambler for political, psychological,

and personal reasons. In examining these films we are not trying to

raise an alarm about the encroachment of gambling into our society, nor are

we encouraging gambling in movies. Rather, it is our hope that understanding

the depiction of gambling in films will assist us in mapping out the

obstacles and opportunities that might be present along the road towards

greater public awareness of the potential negative side effects of gambling.

Method

Sample

Several hundred films were considered in the

process of conducting this study. Sixty-five films were viewed and discussed

in this article. The authors conducted a purposive sampling of films that had

a focus on gambling. The purpose was to allow us to construct a complete

understanding of gambling as seen in recent films. Most of the films listed

here are relatively recent films produced within the past 20 years, but we

have also listed a few older films that we felt were excellent exemplars of

themes. The chart in Figure 1 summarizes the release dates of the films

reviewed in this article.

The first two authors are both avid

enthusiasts of movies about gambling. Many of the films we discuss are

personal favourites that we have watched several times (e.g., Rounders, The Hustler, Vegas Vacation, The Godfather). Some of the films reviewed in this

article have been also discussed by Gluss and Smith

(2001), Dement (1999), and Hayano (1982). Some

films were included because they were found listed as gambling films in film

catalogues or by Web searches for "gambling movies" (e.g., Get Shorty).

Other films were suggested to us by recovering pathological gamblers,

counsellors specializing in problem gambling, recreational gamblers, video

rental store employees, and postings to the bulletin board of Gambling Issues

International (a listserve for gambling treatment

professionals). Our examination of movies was restricted to movies released

in cinemas (i.e., not television), and filmed in English (with one exception, Pig's Law).

Procedure

The authors conducted a purely exploratory

study of gambling in movies. The only starting point in our exploration was Dement's (1999) discovery of irresponsible endings in

films about pathological gambling. We started with this view, but wanted to

look at gambling broadly defined, not just pathological gambling.

In all cases, either the first or second

author viewed each film. In some cases both authors viewed the same film

separately. The authors then discussed the themes that they thought were

depicted in the film. The authors then collected the descriptions of movies

and organized them into general themes.

Results

Dement (1999) primarily focused his

examination on the irresponsible messages in many films about pathological

gambling. We took a different approach and instead extracted from these films

several different themes. Following along from Dement's work, we first identified movies about pathological gambling. However, we

also identified several other movies that focused more on the skill of the

professional gambler. As a result we collected these together into a separate

category of movies about professional or skilled gamblers. As we worked our

way through this list of films, we uncovered two other themes: miraculous

wins and negative stereotypes of gambling. Each time we added a movie to our

list, we searched for additional themes that were emerging.

As the number of films increased, we realized

that negative images of gambling could be further divided into themes of

"cheating," "suckers," and "crime." As more

films were added, the crime theme was sub-divided into movies about crimes

committed against a casino, and movies about criminals who run gambling

operations. These seven categories thus completed our venture into the themes

of gambling films.

However, we had an additional collection of

titles that did not fit into these categories. These films made reference to

gambling, but were not about gambling. We collected this last assortment of

movies into an eighth theme: movies in which a gambling venue or gambling

activity has a symbolic function in the story. These eight themes are not

distinct but overlap. Several movies were related to more than one theme.

Some of the films that we examined did not fit into any of the categories

discussed in the article (e.g., The Odd

Couple, Guys and Dolls). The

rest of the Results section is made up of a list of themes with a description

of the movies that illustrate each theme and detailed discussion of these

themes.

Theme one: Pathological/problematic gambling

Dement

(1999) identified numerous films that depicted a pathological gambler. Many

of these films included accurate portrayals of problematic gambling. However

this accuracy was often undermined by irresponsibly happy endings.

·

Fever

Pitch (Fields & Brooks, 1985) is an accurate

portrayal of pathological gambling, but the movie is severely undermined by a

Hollywood

happy ending.

·

The Gambler (Chartoff,

Winkler, & Reisz, 1974) is about a college

professor and gambler who is so egotistical that he believes

he can change reality by force of will. He is forced to fix a basketball game

to pay off a gambling debt.

·

The Great Sinner (Reinhardt & Siodmak, 1949) portrays a man who becomes addicted to

gambling after his first spin of a roulette wheel.

·

In Let It Ride (Giler & Pytka, 1989), the

main character is a pathological gambler who experiences an amazing winning

streak.

·

In Lost in America (Katz

& Brooks, 1985) a couple hits the road to "find themselves,"

but the wife loses the family's nest egg of over $100,000 at their first stop

―Las Vegas.

·

Owning Mahowny (Camon, Hamori, McLean, & Kwietniowski,

2003) is the true story of a

·

Pig's Law (Bonin, Veillet, & Canuel,

2001) is the story of a young woman who steals drugs to pay her gambling

debts. She is murdered as a result.

·

The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas (Spielberg, Cohen, &

·

In California Split (Altman

& Walsh, 1974), two gamblers go on a gambling spree and drinking binge.

·

In Vegas Vacation (Weintraub & Kessler, 1997) a man sits down at a blackjack

table and obsessively gambles away his life savings.

·

The Hustler (Rossen,

1961) is about a showdown between two highly skilled pool players.

·

White Men Can't Jump (Lester, Miller, Rappaport, & Shelton, 1992) is about men who try to

make a living gambling and playing basketball. The main character is a

skilled player, but addicted to gambling.

·

Two for the Money (Cohen, Robinson, & Caruso,

2005) depicts the inner workings of a sport advice service. The owner appears

to be addicted to everything that one can be addicted to including gambling.

Several movies have included characters who

have a problem or who develop a gambling problem during the movie. However,

few explore the reasons for the problem. The

Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas,

Vegas Vacation, and Lost in America show gambling problems developing rapidly. In most cases, no explanation of

the development of the problem is given whatsoever. In Owning Mahowny, we see the experiences,

temptations, and thoughts that explain Dan Mahowny's (Philip Hoffman's) gradual slide into greater and greater levels of

embezzlement. However, the origin of Mahowny's gambling problem itself is completely unexplored. Similarly, The Gambler includes a few scenes in

which Axel Freed (James Caan) justifies his

irrational behaviour as a conscious exercise of free will and power. However,

the development of the disorder per se is not explored.

The Flintstones in

Viva Rock Vegas is one of the few movies that explore the motivations for problematic

gambling. Fred Flintstone feels he needs to impress Wilma because of her

family's wealth. This is followed by a casino-manipulated series of wins (see

Turner, 2001, for a full review). The combination of emotional need and a

series of wins (intermittent reinforcement) are a reasonably accurate

explanation of problematic gambling. However, both Fred's addiction and his

subsequent escape from gambling occur too easily.

Dement (1999) describes several films about gambling

problem as irresponsible because they tack on a happy ending that leaves the

viewer with the impression that the gambler can win it all back. Fever Pitch, Let It Ride, Two for the

Money, and Vegas Vacation are

particularly apt examples of films with irresponsible happy endings. Owning Mahowny,

The Gambler, and The Hustler are probably the most "responsible" movies about problem gambling

that we have seen.

Very few of these films ever show the gambler

getting any help. In The Gambler and Dinner Rush (DiGiaimo, Greaney & Giraldi, 2000), another character encourages the

pathological gambler to seek treatment, but nothing more. Fever Pitch (1985) shows a gambler

attending a Gamblers Anonymous (GA) meeting. However, after the GA meeting,

the main character goes back to gambling, has a lucky streak, and wins back

just enough to pay off his $89,000 debt. Two

for the Money (Cohen, Robinson, & Caruso, 2005) has a brief episode

in which the two main characters attend a GA meeting, but then try to drum up

business for their sports advice service. Owning Mahowny (2003) shows Mahowny at the beginning and end of the movie talking to a therapist about how he

will live without gambling. The movie does not show very much about the

process of treatment, but the use of a treatment session to resolve the plot

is a vast improvement compared to most movies in this group.

The Hustler and White Men Can't Jump are of interest because they explore

problematic gambling in games of skill. Both illustrate how a highly skilled

player can be a pathological gambler if he lacks emotional control. In The Hustler a contrast is drawn

between Fast Eddie (Paul Newman) and Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleason). Fast

Eddie loses their first tournament together because of his over confidence

and his drinking. He is emotionally crushed by the defeat. In contrast, when

Minnesota Fats is defeated near the end of the movie, he graciously accepts

defeat, shakes Fast Eddy's hand and goes on with his life. But Fast Eddy gets

into a fight over the table fees and is barred from the games room.

Theme two: The almost

magical skill of the professional gambler

However, not all movies about gambling are

about problem or pathological gamblers. The second theme to emerge during our

exploration of movies was the depiction of the almost magical skill of the

gambler. This theme is most often related to skill games but the role of

skill in these games is often exaggerated.

·

In The Cincinnati Kid, (Ransohoff & Jewison, 1965) a

young and highly skilled poker player (Steve McQueen) tries to prove to

everyone that he is now the master of the game.

·

Maverick (Davey & Donner, 1994) is about an extremely skilled

gambler trying to get into a Winner Take All poker tournament.

·

Rounders (Stillerman, Demme, & Dahl, 1998), is about a skilled poker player who has a nearly magical ability to figure

out his opponents hand.

·

In Rain Man (Johnson &

Levinson, 1988) a man with autism is also mathematically gifted and is able

to count cards flawlessly.

·

James Bond films such as Never

Say Never Again (Schwartzman, & Kershner 1983), Diamonds are Forever (Broccoli, Saltzman, & Hamilton, 1971), and Thunderball (McClory & Young, 1965), often have at least one

episode where James Bond demonstrates a magical ability to win gambling

games.

·

The Hustler (1961) is a story about a pool

hustler player who makes his living getting people to bet against his ability

to sink impossible shots.

·

White Men Can't Jump is a story about basketball

hustlers. One of them is extraordinarily good at sinking 3-point shots, but

cannot dunk.

·

Two for the Money (Cohen, Robinson, & Caruso,

2005) depicts the career of a sport tout who is extraordinarily good at

picking winners for the first half of the movie.

In a skill-oriented game such as

poker, pool, basketball, horse racing, or sports betting, long-term success

is theoretically possible. With the exception of some of the James Bond

movies, these films illustrate play in skill games. However, the level of

expertise is often highly exaggerated. In one scene in Rounders, Mike (Matt Damon)

watches a group of professors playing poker for a few seconds, and then tells

each of them exactly what they are holding. The main characters in The Cincinnati Kid and Maverick also show a magical ability

to read their opponents' hands. In Rain

Man, the autistic savant Raymond's (Dustin Hoffman) mathematical skill makes a

blackjack game a sure victory. Card counting is indeed possible, but it only allows

a card counter an edge of 1% or 2% over the house. The Hustler and White Men Can't Jump illustrate

a magical ability to make impossible shots. Similarly, no matter what

game James Bond plays, he is always able to win and prove that he deserves

the designation of being lucky agent 007. He can even win games that he has

never played before or games of pure chance such as craps (Diamonds are Forever). Bond films have

been added to this category because these wins are portrayed as part of his

overall secret agent skill. These movies glamorize professional gamblers and make skilled play

seem like a sure thing.

Theme three: Miraculous

wins as happy endings

The wins discussed above

were the result of skill. However, many movies end with a miraculous win.

Dement (1999) calls these sorts of films irresponsible because they encourage

gamblers to hope to win.

·

Fever Pitch (1985) is the story of a

pathological gambler who goes on a spree and wins back the money he lost.

·

In Vegas Vacation (1997),

Clark Griswold (Chevy Chase) loses all of

his family's money, but then is given a winning keno ticket from a dying man.

·

In Let It Ride (1989) a

chronic loser, Jay Trotter, (Richard Dreyfuss) has an

incredible winning streak at the races. For one race, he picks a horse for

the sole reason that none of his racetrack friends have picked it.

·

In Rounders (1998), Mike wins the big showdown at

the end of the movie and goes off to

·

In Stealing Harvard (Cavan

& McCulloch, 2002), a young man needs money to pay for his niece's

education. He unsuccessfully tries to steal the money, gives up, and instead

wins the money he needs at a racetrack.

·

In The Good Thief (Seaward,

McLean, Wells, Woolley, & Jordan, 2003), Bob

the gambler (Nick Nolte) manages to quit heroin, find love, pull off a major

theft of a casino, and has an incredible lucky windfall at the casino.

·

The Cooler (Furst, Pierce, & Kramer, 2003) tells the story of a person with chronic

bad luck who works in a casino to "cool" the luck of winning

players. His luck changes when he falls in love.

·

In Two for

the Money, after a disastrous losing streak, Brandon Lang (Matthew McConaughey)

makes one last pick by flipping a coin. It wins.

The miraculous wins in these movies are often

simply the usual

Hollywood

happy ending.

People often go to movies for entertainment and escape so it is not

surprising that they want a happy ending. The movie Vegas Vacation, for example, was a comedy and so the writers

likely felt that they could not leave the Griswold family destitute.

Additional irresponsible comedy was added by the contrast between the father

(Chevy Chase) who lost virtually every time

he played and his underage son (Ethan Embry) who won every time he played.

Many comedies that have nothing to do with gambling have financially happy

endings. Stealing Harvard is

interesting in this respect because until the final scene the movie has

nothing to do with gambling. Gambling is merely used as the means towards a

happy ending.

However, the down side of the happy ending in

films about gambling is that it may encourage distorted expectations about

winning. Some viewers may take the magical ending seriously and be encouraged

to chasing losses while gambling.

The main character in The Cooler (2003) suffers from

contagious bad luck. The movie informs us that at one time he suffered from a

gambling problem that resulted in a massive debt. The mob boss/casino owner

had his legs damaged to punish him, but then employed him to kill the luck of

other players. He walks around the casino touching tables or merely walking

by slots and bad luck happens to the players. However, this all changes when

he becomes involved in a mutual love relationship and the opposite starts to happen―he develops a case

of infectious good luck. At the end of the movie, he walks out of the casino

with a huge sum of money. The Cooler is filled from end to end with superstition and erroneous beliefs. The movie

gives the viewer the impression that without the cooler on staff, the casino

would lose money.

The reification of luck

is not unique to gambling movies. In the recent movie Holes (Blank,

Theme four: Gamblers are suckers

There are a number of movies that portray

highly negative images of gamblers.

·

In Casino (De Fina & Scorsese, 1995), the casino's customers are

shown as suckers, criminals, or degenerates.

·

In Croupier (Cavendish, De Mardt, Olen, Ruppert, &

Hodges, 2000), the main character and narrator seems to view all gamblers as

addicts or cheats.

·

Mafia (Badalato &

Abrahams, 1998) is a parody of movies about organized crime such as Casino.

·

In Two for

the Money we are told that all the people who call the sports advice

service are "hooked." The character

Brandon

is told to "reel them

in."

Films in this category exhibit a negative

attitude towards the ordinary gambler, often viewing all players as addicts.

For example, in Croupier, the main

character and narrator calls the casino the "house of addiction"

and tells his girlfriend that gambling is about "not facing reality" and "ignoring the odds."

Later the narrator goes on to conclude that the gambler is not self-destructive,

but rather wants "to destroy everyone else." Similarly, in Two for the Money, Walter (Al Pacino) tells us that all of the customers of the sports

advice service are addicts. This attitude is also echoed in an interview with

the real person on whom the character

In Casino, the key scenes that reveal the

movie's attitude towards the players are those narrated by Sam

"Ace" Rothstein (DeNiro), in which he

describes the operation of the casino or the counting room. During these

scenes, he makes a number of comments about the suckers who come to

Mafia is a parody of Casino. It takes the negative view of

gamblers one step further by explicitly making fun of the

players. The slot machines come with

names such as "Kiss your Money Good-bye," "Last Red

Cent," and "Big Loser." There is also a table game

called "You Absolutely Can't

Win" where the customers put their money on the table and the dealer

takes the money, stuffs it in a hole and says "thank you for

playing." Another dealer uses a vacuum cleaner to remove bets from the

table. The narrator goes on to say that "smart ones" just send the

casino the money and save "the plane fare."

Theme five: Gamblers cheat

Several movies show people cheating in order

to win. In some movies the casino is also shown cheating, but more often it

is the player.

·

In Rounders (1998), Mike's friend Worm seems to be a pathological liar. No matter how

often Mike tells him not to cheat, Worm keeps cheating.

·

In Cincinnati Kid (1965),

the dealer tries to help the main character by stacking the deck. The

Cincinnati Kid refused to allow any cheating.

·

In House of Games (Hausman & Mamet, 1987), a

poker player talks a psychiatrist into helping him cheat.

·

The Sting (Bill, Phillips, Phillips,

Phillips & Hill, 1973) is centred around using a

fake off-track betting parlour to lure a Mafia leader into a major con.

·

In Maverick (1994), in the

final hand at a poker table, the cards are stacked to draw all the players

into the showdown for a huge pot of money.

·

In Lucky Numbers (Daniel, Ephron, Krane, Lazar, & Ephron Resnick, 2000), three

friends conspire to rig the lottery.

·

Eight Men Out (Pillsbury, Sanford, &

Sayles, 1988) focuses on the alleged fix of the 1919 World Series by

gamblers.

·

In The Flintstones in Viva Rock

Vegas (2000), Fred Flintstone is treated to an unusually long winning

streak and then the casino owner throws a switch and Fred loses everything.

·

In Austin Powers: International

Man of Mystery (Moore, Myers, Todd, Todd, & Roach, 1997), one of Dr.

Evil's henchmen, Number Two, is playing blackjack with X-ray glasses so that

he can read the next card in the deck.

·

In Waking Ned Devine (Holmes, Murray, & Jones, 1998), two men discover the dead body of a

friend who appears to have died of a heart attack upon winning a major

lottery. They try to claim the prize.

·

The Cooler (2003)

shows a player, the main character's son, cheating at craps.

·

Shade (Hammond, Hartley, Schnepp, & Niemanm, 2003) is about a gang of poker hustlers who are

anxious to prove that they are better at cheating than The Dean (Sylvester

Stallone).

·

Croupier (Cavendish, De Mardt,

Olen, Ruppert, & Hodges, 1998) has several scenes of players or dealers

cheating.

·

In

·

In Finder's Fee (Arragon, Wallin, Williamson,

& Probst, 2001), a man discovers a wallet

containing a winning lottery ticket.

·

Rat Race (Daniel, Zucker,

& Zucker, 2001) depicts a race staged by a

casino owner to give his high rollers something unique to bet on.

·

In The Grifters (Scorsese, Harris, Painter & Frears, 1990), a

con artist works for a bookie, placing bets to change the odds at the track.

According to these movies gamblers are dishonest

people. Finder's Fee, for example,

suggests that even honest nice people will cheat when the prize is large

enough. Rat Race suggests that

people will do anything whatsoever to win a prize. In Austin Powers, The Sting, and Waking

Ned Devine the cheaters are successful and keep their wins. However, in Rounders, Casino, and The Cooler the cheaters are caught and dealt with rather harshly.

In Croupier, cheaters were dealt

with in a more legal manner being either barred from the casino or arrested.

However, in The Cincinnati Kid and Rounders the

main character refuses to win by cheating.

The casino also cheats

in some movies. In four movies―Viva Rock Vegas, The

Sting, Croupier, and

Theme six: Organized crime runs the game

The management of the casino is also

portrayed in a negative light. Several movies draw a strong link between organized

crime and casinos. While organized crime has definitely been involved in

gambling in the past, this stereotype appears to be persisting.

·

In The Dinner Rush (DiGiaimo, Greaney, & Giraldi, 2000), the owner of a restaurant is threatened

by the Mafia over his son's gambling debts.

·

Casino (1995) depicts gangster involvement in

·

In The Godfather (Ruddy

& Coppola, 1972) and The Godfather II (Coppola, 1974), the Mafia Corleone family runs casinos in

·

In The Flintstones in Viva Rock

Vegas (2000), a rich criminal runs the casino.

·

In The Mask (Engelman & Russell, 1994), gangsters run

·

Mafia (1998) is a spoof on Mafia movies such as The

Godfather and Casino.

·

Get Shorty (1995) is centred on a loveable

"Shylock" played by John Travolta, in search of a gambler who owes

him $15,000.

·

In The

Cooler (2003) the casino is run according to the "old school"

which means gangster style.

·

Bugsy (Beatty, Johnson, & Levinson, 1991)

is about the life of Benjamin "Bugsy"

Siegel, who in the 1940s set up the Flamingo, the first major destination

casino on the Las Vegas Strip.

·

In Walking Tall (Briskin, & Karlson, 1973; Burke, Schiff, Foster, Amritraj, Hoberman, & Bray, 2004) a man returns

home and finds that a corrupt casino owner controls his town. The casino uses

loaded dice to cheat the players.

Gambling produces a lot of money and criminal

involvement is not surprising. Movies such as Casino, Bugsy, and The Godfather series are based in part on actual events and are

reasonably accurate portrayals of the historical link between gambling and

organized crime (Asbury, 1938; de Champlain, 2004). However, in our view modern

The link between gambling and criminals is also

hinted at in many other films discussed in this article including James Bond

movies, The Hustler, The

Theme seven: Stealing from a casino

Another popular

genre of gambling-related film is the casino heist movie. This theme is

closely linked to the "gamblers as cheaters" theme, but instead of

stealing by cheating, the characters try to steal the casino's money

directly. There have been several recent examples of films in this genre.

These films often make the thieves seem glamorous and their theft seems

justified.

·

Both versions of Ocean's

Eleven (Weintraub & Soderbergh,

2001; Milestone, 1960) are about a casino heist. The robbers are likeable and

funny.

·

3000 Miles to

·

In Croupier (2000), the main

character, who works in a casino, becomes involved in a plot to rob his own casino.

·

The Mask (1994) contains all the

stereotypes of crime and gambling. Dorian's gang of thieves robs a casino and

attempts to blow it up with people still inside.

·

Lady Killers (Ashley, Greenspun,

& Preisler, 2004) follows the exploits of an

eccentric group of criminals who successfully rob a riverboat casino.

·

Reindeer Games (Moore, Weinstein, Katz, & Frankenheimer, 2000) is one of the few films set in a

seedy casino. The casino owner is heavily armed.

·

In The Good Thief (2003), a

thief addicted to drugs and gambling successfully robs a

Monte

Carlo

casino.

Movies that depict people trying to rob

casinos do not seem to have any difficulty showing the thieves as heroes. It

is as if the audience is being invited to feel some sort of satisfaction of

vengeance against the casino. In Ocean's

Eleven (2002), there is a strong hint that the casino operator is a

criminal, so in trying to rob the casino the heroes are merely taking money

back from the underworld. In The Good Thief the casino management is shown as being snobbish. In The Good Thief and in Ocean's Eleven, the crime does pay and

the thieves are successful. The idea that casinos deserve to be robbed is

most clearly stated in Lady Killers when Professor G.H. Dorr (Tom Hanks), tells his landlady that that there is

no crime in robbing the casino because her "gains are ill gotten."

The thieves in these films are not always

heroic. The Mask depicts the

thieves who plan to steal the "Orphan fund" as evil. In 3000 Miles to Graceland Thomas J.

Murphy (Kevin Costner) is a psychotic killer. However, another thief, Michael

Zane (Kurt Russell) is heroic and manages to end up with love, a family, a

boat, and a lot of money.

Theme eight: Gambling as a symbolic

backdrop to the story in the film

This theme is different because it does not

actually involve gambling per se, but the incidental appearance of gambling

or gambling-related places in movies. Even movies directed towards children

may have scenes of

·

Looney Tunes Back in Action (Abbate, DeFaria, Goldmann, Simon,

Weinstein, & Dante, 2003) is an adventure involving Daffy Duck, a

security guard, and a plot for world domination. The characters have to go to

·

Mars Attacks (Franco & Burton, 1996). This

movie is a comedic retelling of the War

of the Worlds. Some scenes are set in

Las Vegas.

·

Leaving

·

Pay It

Forward (Abrams, Levy, Reuther, & Leder, 2000) is a movie about a boy who tries to make

the world a better place with random acts of kindness. The boy's mother works

in a casino as a waitress.

·

In Stealing Harvard (2002),

the financial salvation of the story comes from gambling.

·

Four Dogs Playing Poker (Hoffman, Salinger, & Rachman, 1999) is a violent movie about art theft that

uses poker as a metaphor for the intrigues of the plot.

·

Fear and Loathing in

·

Snake Eyes (De Palma, 1998) is a dramatic movie

about a politically oriented crime. The movie is set in a casino in

·

Shark Tale (Damaschke,

Healy, Segan, Bergeron, Jenson, & Letterman,

2004) Oscar owes $5000 to his boss. His girlfriend gives him $5000, but he

bets it on a sea horse. This crisis leads Oscar into his role as (fake) shark

killer.

The cameos of

Leaving Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas depict the seedy side of

Snake Eyes and Four Dogs Playing Poker use gambling as a metaphor for the

high-risk games that the various characters are playing. Other films use

gambling as a plot device to create a crisis (Shark Tales, Viva Rock Vegas), or a solution (Stealing Harvard). Shark Tales (2004)

also uses Oscar's disastrous foray into gambling as a metaphor for his

short-sighted dreams of grandeur during which he ignores the fish that really

loves him. Pay it Forward uses the

randomness of gambling as a backdrop to Trevor McKinney's (Haley Joel Osment) attempt to make the world a better place through

random acts of kindness. The symbolic meaning of gambling as used in these

films varies from glamour to decadence, and from

hope to hopelessness. What binds this assortment of films together into a

theme is the use of gambling in a symbolic manner.

A taxonomy of themes

As discussed above, we identified these themes by reviewing numerous films and summarizing their content. We have organized these themes into a general taxonomy of films that is presented in Figure 2. First these films can be divided into two categories: films in which gambling is a central focus of the film, and others where gambling is a relatively minor topic but serves a symbolic role in the film. The films that are about gambling can be further divided into those that present generally negative views of gambling (e.g., pathology, crime, cheating) and those that present a generally positive image of gambling (e.g., magical skills and miraculous wins). The positive image is mainly related to the ability of the player to win (by skill or by miracle), but some of these films also add additional positive images by hinting at a glamorous and exciting lifestyle (The Good Thief, James Bond films, Rounders). Negative images of gambling are more common than positive images of gambling. Negative images were further divided into pathological gambling, suckers, cheaters, organized crime, and robbing casinos.

Release

dates and trends in themes

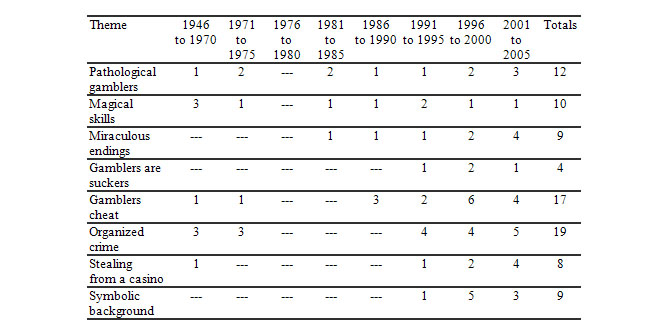

As a final analysis we also looked

at the release dates to see if we could detect any trends in relative

frequency of themes. Table 1 summarizes the release dates of the films by

thematic category. Overall, the two most common themes were cheating and

organized crime. Movies about pathological gambling appear to be the most

stable category of film, occurring at a steady rate throughout the past 40

years. The theme of magical skill appears to have declined. Out of the 17

movies released between 2001 and 2005, only one, Two for the Money (2005) could be said to show magical skill. In

contrast, films with lucky endings have been quite common in recent years.

Movies specifically about gambling and organized crime (e.g., The Godfather series) have declined

somewhat in recent years (see exemplars in the section on Organized Crime).

However, when we added to this list the number of movies that hint at

organized crime (e.g., Ocean's Eleven,

The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas, Shade, Owning Mahowny)

then the numbers in this category show no sign of decreasing. The most

noticeable trend is the number of recent films about a casino heist. The

movies in this study were not sampled randomly nor were they sampled

consistently across time. As a result we cannot draw any firm conclusion

about trends over time in themes. Table 1 is offered here only as a guide to

future research.

Discussion

As stated in the introduction, the purpose of

this article is to examine the images of gambling found in motion pictures.

It is our hope that an understanding the depiction of gambling in films will

assist us in mapping out the obstacles and opportunities that might be

present along the road towards greater public awareness of the potential

negative side effects of gambling. In this article, we identified and

described eight overlapping themes represented in movies about gambling. In

summary these themes are as follows: (1) pathological gambling, (2) the

magical skill of the professional gambler, (3) miraculous wins as happy

endings, (4) gamblers are suckers, (5)

gamblers cheat, (6) gambling is run by organized crime, (7) the casino heist,

and (8) gambling as a symbolic backdrop

to the story in the film. Figure 2 organizes these themes into a taxonomy of film themes.

Figure 2. Taxonomy of films about gambling

with exemplars for terminal categories.

Note: Bold titles indicate terminal

categories with exemplars.

Throughout the history of movies,

gambling-related stories have been present. Movies about gambling are most often inhabited by problem gamblers (e.g., The Gambler), cheats (e.g., Shade), criminals (e.g., The

Godfather, Ocean's Eleven), spies (e.g., Diamonds are Forever), people

with incredible luck (e.g., Stealing

Harvard), and professional gamblers (e.g., Rounders, The Hustler). With the exception of The Odd

Couple (1968), we have come across few movies that show ordinary

people gambling in a non-problematic manner.

Table

1

Themes and release dates of movies

Note that several movies appear in more than one

category.

Hayano (1982) noted that movies set in

the old west were often neutral about gambling (e.g.,

Tombstone, Maverick). The games were shown as

part of ordinary life. In contrast he found that films set in cities included

negative depictions of gambling, including a strong link with crime. Negative

images of gambling still persist, but today, these are mixed in with images

of incredible luck. It seems that when

movie producers turn their attention to gambling, they insist on illustrating

extremes. This is likely due to the pragmatics of telling an exciting story,

but it leaves the audience with false stereotypes and erroneous images of

gambling.

There appears to be ambivalence towards

gambling in many of these films. On the one hand, gambling venues are shown

as exciting and glamorous places where men dress in suits and women dress in

evening gowns (Ocean's Eleven, Rounders, The Good Thief), and spies prove that they can beat the odds (Diamonds are Forever, Austin Powers, Loony

Tunes Back in Action). On the other hand, many films suggest that casinos

are run by criminals (The Godfather,

The Cooler) or deserve to be robbed (Ocean's

Eleven, The Good Thief, 3000 Miles to

Graceland,

The Lady Killers). As another example, in The Godfather, Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) tells us that gambling is just a "harmless

vice" that people want, whereas drugs are a "dirty business."

However, when Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) launches his new career as a legitimate businessman―a casino owner―he does so by organizing the simultaneous murder of all of his enemies.

Some movies provide important insights into

the nature of pathological gambling (e.g., The Gambler, Owning Mahowny, The Hustler). However, others make light of the

disorder or indulge in the wishful thinking common with pathological gamblers

(e.g., Let It Ride, The Cooler, Fever

Pitch, The Good Thief). In some movies people develop a problem too

quickly (Viva Rock Vegas, Lost in

We have also found a number of errors in the

depiction of games in these films. For example, in the film

Tombstone

there were several errors in the layout of the faro tables shown in the film

and the manner in which the game was conducted (see Howard, 2004). Similarly

the cheating by the casino in Walking

Tall (1973, 2004) made no sense given the rules of craps. Because the

players roll the dice and can bet on many possible outcomes, loaded dice

would be an advantage to the player, not the house. In Two for the Money, the sports touts place an extraordinary

emphasis on the outcome of single games. Real handicapping is a process of

finding a small advantage across numerous games and playing the odds. Another

error is the exaggeration of the power of skill in leading to a win. In Rain Man, for example, a man with

autism is somehow able to learn to count cards in blackjack so well that he

can predict virtually every hand. Finally, Shade was completely out of touch with the modern reality of

high-stakes poker.

Some movies appear to

be confused about the concepts of luck and skill. James Bond films frequently show Bond

playing games of chance (baccarat and craps) as if they were games of skill. Whatever the game, Bond always has the skill to

outplay his opponents. In contrast, Let It Ride portrays horse racing as if it was a game of pure

random chance.

Many movies portray a distorted reality in

which fantastic wins (e.g., Let It

Ride, The Cooler, Fever Pitch) or magical skills (The Hustler, Rain Man, Rounders, Diamonds

are Forever) lead to success. Other films present a distorted image of

how the casino makes money (The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas, The Cooler,

Walking Tall). Fred Flintstone

loses because the casino owner pulls a switch that sets the games from

"win" to "lose."

Similarly The Cooler suggests that the casino

can only make it if it employs someone with bad luck to protect its profits.

In many cases these distortions coincide with erroneous beliefs about beating

the odds held by many pathological gamblers (see Ladouceur, & Walker, 1996; Wagenaar, 1988). Bandura (1977;

1986) has argued that people learn through the imitation of models. In this

respect films with happy endings due to wins such as Fever Pitch, The Cooler, and Vegas

Vacation might be teaching potentially harmful lessons about gambling. Vegas Vacation is particularly

distributing because it shows a youth obtaining a fake identification card

and then winning on every game he plays. Any message that one might gain by

watching the father's (Chevy Chase)

disastrous gambling is undermined by the success of his son (Ethan Embry).

Gupta and Derevensky (1997) have shown that children's attitudes towards gambling are shaped by

parental modeling of gambling. They found that children often learn how to

gamble from their families. However, little research has been conducted on

youths to determine how they are influenced by movies about gambling.

Summary

Movies present the

audience with very distorted images of gambling. In

addition they often fail to provide the audience with portrayals of

responsible gambling. The film images of incredible luck are more likely to

encourage irresponsible gambling. It could be argued that the purpose of a movie

is to provide fantasy, rather than education. In addition, as works of art

films have no obligation to be accurate. However, it is important to consider

to what extent the producers and distributors of a film should be responsible

for its content. It is likely that a film that encouraged excessive drug use

or showed true happiness stemming from an addiction would at the very least

come with a warning about its content. The

This discussion of films has a number of

limitations. The films discussed were neither a random sample, nor a

comprehensive sample. We cannot generalize in terms of the relative frequency

of the themes discussed. We have also limited ourselves for the most part to

films shown in English, although Web searches identified several films that

were not in English. In addition we have only superficially looked at the timeline

of the movies we examined to see if there are trends in the themes or the

number of films changing over time. A future direction of research would be

to examine movies about gambling across time in a more comprehensive manner

to see if there are indeed shifting trends in the themes in these movies.

References

American

Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic

and statistical manual of mental disorders.

Washington,

DC:

Author.

Asbury,

H. (1938). Sucker's progress: An

informal history of gambling in

America.

New York: Thunder Mouth Press.

Bandura,

A. (1977) Social learning theory.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory.

de Champlain, P., (2004). Mobsters, gangsters and men of honour: Cracking the

Mafia code.

Toronto:

HarperCollins.

Dement,

J.W. (1999) Going for broke: The

depiction of compulsive gambling in film.

Lanham,

MD:

The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Dorion,

J.P., & Nicki, R.M. (2001). Epidemiology of

problem gambling in

Prince Edward

Island: A Canadian microcosm. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 46, 413–417.

Gluss,

H.M. & Smith, S.E., (2002). Reel

people: Finding ourselves in the movies. Keylight:

Los Angeles.

Griffiths, M. D. (2004). An empirical analysis of the

film, "The Gambler." eCOMMUNITY: International Journal of Mental Health

& Addiction, 1(2). Accessed

May 1, 2007 from http://www.ijma-journal.com/issues/issue/1/2

Gupta,

R., & Derevensky, J. (1997). Familial and

social influences on juvenile gambling behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 13(3), 179-192.

Hayano,

D. (1982). Poker faces: The life and work of professional players.

Berkeley,

C:

Howard,

M. (2004). Bucking the Tiger –

The Traditional Game of Faro. Available at http://www.bcvc.net/faro/

Kearney,

Ladouceur, R., &

Walker

, M., (1996). A cognitive perspective

on gambling. In P.M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Trends in cognitive and behavioural

therapies (pp. 89-120).

Chichester,

NY: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Room, R. Turner, N.E., & Ialomiteanu, A. (1999) Community effects of the opening

of the Niagara Casino: A first report. Addiction,

94, 1449-1466.

Rose,

I.N. (1986). Gambling and the law.

Los Angeles: Gambling

Times.

Rush, B., Moxam Shaw, R., & Urbanoski,

K. (2002). Characteristics of people seeking help from specialized programs

for the treatment of problem gambling in

Ontario. Electronic Journal of Gambling

Issues: eGambling:, 6, 32–54 [Online]. Accessed

April 30, 2006: http://www.camh.net/egambling/issue6/research/index.html

Sargent,

J.,

Shaffer,

H. J, Hall, M.N., Vander Bilt, J. (1999) Estimating

the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the

Smith,

G.J., & Wynne, H.J. (2004). VLT gambling in

Alberta: A preliminary analysis.

http://www.abgaminginstitute.ualberta.ca/documents/research/VLT_Gambling_Alberta.pdf

Tremblay,

G.C., Hoffman, L., & Drabman, R. (1998). The

effects of modeling and experience in young children's persistence at a

gambling game. Journal of Gambling

Studies, 14 (2), 193-210.

Turner,

N.E. (2001). The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas: A review. Electronic Journal of Gambling Issues: eGambling, 3. Accessed April 30, 2006: http://www.camh.net/egambling/issue3/review/index.html#flintstones

Twain, M.

(2004). The professor's yarn. An excerpt from Life on the Mississippi, 1882. Reprinted in J. Stravinsky (Ed.), Read 'em and weep: A bedside poker companion (pp 209- 215)

New York: Harper

Collins.

Wagenaar,

W.A. (1988). Paradoxes of gambling behavior.

London:

Films reviewed

Abbate, A., Goldmann, B., Weinstein, P., deFaria,

C., Doyle, L., Simon, J. (Producers), & Dante, J. (Director). (2003). Looney tunes: Back in action [Motion

picture].

United States:

Warner Bros.

Abrams,

P., Levy, R.L., Reuther, S. (Producers), & Leder, M. (Director). (2000). Pay it forward [Motion picture].

United States: Warner Bros.

Altman,

R. (Director & producer), & Walsh, J. (Producer). (1974).

Arragon, B.V., Wallin K., Williamson S. (Producers), & Probst, J.

(Director). (2001). Finder's fee [Motion picture].

Ashley, D., Greenspun, A. (Producer), & Preisler,

G. (Producer & Director). (2004). Lady

killers [Motion picture].

Badalato, B., (Producer), &

Abrahams, J. (Director). (1998). Mafia [Motion pictures].United States: Buena Vista Pictures.

Beatty,

W., Johnson, M. (Producer), & Levinson, B. (Producer & Director).

(1991). Bugsy [Motion picture].

United States:

Columbia

TriStar Films.

Bill, T.,

Phillips, J., Phillips, M., Phillips, M.S., (Producers), & Hill, G.R.

(Director). (1973). The sting [Motion picture].

Blank,

L.D.,

Bonin, J., Veillet,

C. (Producers), & Canuel, E. (Director).

(2001). Pig's law [Motion picture].

Broccoli,

A.R, Saltzman, H. (Producer), & Hamilton, G.

(Director). (1971). Diamonds are

forever [Motion picture].

Burke, J, Schiff, P., Foster, L., Amritraj,

A., Hoberman, D. (Producers), & Bray, K.(Director) (2004). Walking

tall. [Motion picture].United States: MGM.

Briskin, M. (Producer), & Karlson, P. (Director) (1973). Walking tall [Motion Picture].

Camon, A., Hamori,

A., McLean, A. (Producers), & Kwietniowski, R.

(Director). (2003).

Owning Mahowny [Motion

picture].

Cassavetti, P., Nabulsi, L., Nemeth, S. (Producers),

& Gilliam, T. (Director). (1998). Fear

and loathing in

Cavan, S. (Producer), &

McCulloch, B. (Director). (2002). Stealing

Harvard [Motion picture].

Cavendish,

J., De Mardt, M., Olen, B., Ruppert,

C. (Producers), & Hodges, M. (Director). (1998). Croupier [Motion picture].

Cazès,

L., Stewart, A. (Producers), & Figgis, M.

(Director). (1995). Leaving Las Vegas [Motion picture].

Chartoff,

R., Winkler,

I.

(Producers), & Reisz, K. (Director). (1974). The Gambler [Motion picture].

Cohen, B. (Producer), &

Cohen, J,. Robinson J. G. (Producers), & Caruso, D.J.

(Director), (2005). Two for the money.

Coppola,

F.F., (Producer & Director). (1974). The

godfather: Part II [Motion picture].

Damaschke,

B., Healy, J., Segan, A.L. (Producers), Bergeron,

B., Jenson, V., & Letterman, R., (Directors). (2004). Shark tale [Motion picture].

Daniel,S., Ephron, N., Krane, J.D., Lazar, A. (Producers), & Ephron Resnick, N. (Director).

(2000). Lucky numbers [Motion

picture]. Unites States:

Paramount

Pictures.

Daniel,

S., Zucker, J. (Producers), & Zucker, J. (Director/Producer) (2001). Rat race [Motion picture].

United States:

Paramount

Pictures.

Davey,

B., (Producer), & Donner, R. (Director &

Producer). (1994). Maverick [Motion

picture].

De Fina, B. (Producer), & Scorsese, M. (Director).

(1995). Casino [Motion picture].

De Palma,

B. (Producer & Director). (1998). Snake

eyes [Motion picture].

DeVito,

D., Shamberg, M., & Sher,

S. (Producers), & Sonnenfeld, B. (Director).

(1995). Get shorty [Motion picture].

DiGiaimo,

L., Greaney, P. (Producer), & Giraldi, B. (Director). (2000). The dinner rush [Motion picture].

Engelman,

B. (Producer), & Russell, C. (Director). (1994). The mask [Motion picture].

Fields,

F. (Producer), & Brooks, R. (Director). (1985). Fever pitch [Motion picture].

Franco,

L.J. (Producer), &

Furst,

S., Pierce, M.A. (Producers), & Kramer, W. (Director). (2003). The cooler [Motion picture].

Giler,

D. (Producer), & Pytka, J. (Director). (1989). Let it ride [Motion picture].

United States:

Paramount

Pictures.

Goldwyn,

S. (Producer), & Mankiewicz, J.L. (Director),

(1955) Guys and dolls [Motion

Picture].

Hammond,

C., Hartley, T., Schnepp, D. (Producers), & Niemanm, D. (Director). (2003). Shade [Motion picture].

Hausman,

M. (Producer), & Mamet, D. (Director). (1987). House of games [Motion picture].

Hoffman,

S.E., Salinger, M. (Producers), & Rachman, P.

(Director), (1999). Four dogs playing

poker [Motion picture]. Unites States: Warner Home Video.

Holmes,

R., Murray, G. (Producers), & Jones, K. (Director), (1998). Waking Ned Devine [Motion pictures].

Ireland

/

Jacks,

J., Daniel, S., Misiorowski, B. (Producers), & Cosmatos,G. (Director). (1993).

Johnson,

M. (Producer), & Levinson, B. (Director). (1988). Rain man [Motion picture].

Jones,

R., Lyons, J. (Producers), & Anderson, P.T., (Director). (1997). Hard eight [Motion picture].

Kane, M.,

Pressman, E.R. (Producers), &

Katz, M.

(Producer), & Brooks, A. (Director). (1985). Lost in America [Motion picture].

Koch, HW.

(Producer), & Saks, G. (Director). (1968). The odd couple [Motion Picture].

Lester,

D.V., Miller, D., Rappaport, M. (Producers), &

Lichtenstein,

D., (Director & Producer) Manes, E., Samaha,

E., Spero, R., Stevens, A., (Producers), (2001). 3000 miles to

Graceland

[Motion picture].

McClory,

K. (Producer), & Young, T., (Director). (1965). Thunderball [Motion picture].

United Kingdom

/

Milestone,

L. (Producer & Director). (1960). Ocean's

11. [Motion picture].

Moore,

D., Myers, M. Todd, J., Todd, S. (Producers), & Roach, J. (Director). (1997). Austin Powers: International man of

mystery [Motion picture].

Pillsbury,

S. & Sanford, M. (Producers), & Sayles, J. (Director). (1988). Eight men out. [Motion picture].

Ransohoff,

M. (Producer), & Jewison, N. (Director).

(1965). The

Cincinnati

kid [Motion picture].

Reinhardt,

G. (Producer), & Siodmak, R. (Director).

(1949). The great sinner [Motion

picture].

Rossen,

R. (Producer & Director). (1961). The

hustler [Motion picture].

Ruddy,

A.S. (Producer), & Coppola, F.F. (Director). (1972). The godfather [Motion picture].

Schwartzman,

J. (Producer), & Kershner,

I.

(Director). (1983). Never say never

again [Motion picture].

Scorsese

M., Harris R. A., and Painter J. (Producers), & Frears S. (Director). (1990). The grifters [Motion picture].

Seaward,

T.,

McLean

, S., Wells, J., and Woolley, S. (Producers), & Jordan, N. (Director).

(2003). The good thief [Motion

picture].

Stillerman, J., Demme, T. (Producers), & Dahl, J.

(Director). (1998). Rounders [Motion picture].

Weintraub,

J. (Producer), & Kessler, S. (Director). (1997). Chevy Chase's

Weintraub,

J. (Producer), & Soderbergh, S. (director)

(2001). Ocean's eleven. [Motion picture].

Weintraub,

J. (producer), & Soderbergh, S. (director)

(2004). Ocean's twelve. [Motion picture].

Disclaimer:

The ideas expressed in this article are those of the authors and may not

necessarily reflect those of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health or

*******

Manuscript

history: submitted: June 06, 2005; accepted: October 5, 2006. All URLs were

active at the time of submission.

For correspondence: Nigel E.

Turner, PhD, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 33 Russell Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2S1. Phone:

416-535-8501 x 6063; Fax 416-595-6899; E-mail:nigel_turner@camh.net

Contributors: The concept and first draft of

this paper was completed by BF. NT and BF carried out most of the raw

research for the paper. NT with the help of MZ organized the material into

themes. MZ helped revised the paper, expanded on the social context and

corrected errors. NT wrote the final draft. BF handed over first authorship

to NT in June 2004, just before he passed away.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval:

Not required.

Funding:

None.

Nigel Turner (PhD, cognitive psychology,

University of Western Ontario, 1995) wrote his dissertation on the psychology

of figurative language. He has worked at the Addiction Research Division of

the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health for the past 10 years where he has

developed psychometric tools to measure addiction processes. He is currently

focused on understanding the mental processes related to gambling addiction.

He has extensive experience in various research methods including

psychometrics, surveys, experimental studies, computer simulations,

interviews and focus groups.

Barry Fritz. This

article is dedicated to the memory of Barry Fritz (1940 - 2004) (PhD,

psychology,

Yeshiva University,

New York, NY) who passed away

before he could finish this article. He was professor of psychology at

Masood Zangeneh is a research associate at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. He is

also a part-time professor of consumer psychology at the

|

||||||||

|

|

issue 20 — june 2007  |

contents | submissions | links | archive | subscribe

Please note that these links will always point to the current issue of JGI. To navigate previous issues, use the sidebar links near the top of the page.

Copyright © 1999-2007 The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

Editorial Contact: Phil Lange

Join our list to be notified of new issues. Subscribe